- Home

- G. A. Henty

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea Page 9

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea Read online

Page 9

CHAPTER IX.

INKERMAN

It was soon after five in the morning when the pickets of the seconddivision, keeping such watch as they were able in the misty light,while the rain fell steadily and thickly, dimly perceived a gray massmoving up the hill from the road at the end of the harbor. Althoughthis point was greatly exposed to attack, nothing had been done tostrengthen the position. A few lines of earthworks, a dozen guns inbatteries, would have made the place secure from a sudden attack. Butnot a sod had been turned, and the steep hillside lay bare and open tothe advance of an enemy.

Although taken by surprise, and wholly ignorant of the strength of theforce opposed to them, the pickets stood their ground, but before theheavy masses of men clambering up the hill, they could do nothing, andwere forced to fall back, contesting every foot.

Almost simultaneously, the pickets of the light division were alsodriven in, and General Codrington, who happened to be making hisrounds at the front, at once sent a hurried messenger to the camp withthe report that the Russians were attacking in force. The seconddivision was that encamped nearest to the threatened spot. GeneralPennefather, who, as Sir De Lacy Evans was ill on board ship, was incommand, called the men who had just turned out of their tents, andwere beginning as best they could to light their fires of soaked wood,to stand to their arms, and hurried forward General Adam's brigade,consisting of the 41st, 47th, and 49th, to the brow of the hill tocheck the advance of the enemy by the road from the valley, while withhis own brigade, consisting of the 30th, 55th, and 95th, he took poston their flank. Already, however, the Russians had got their guns onto the high ground, and these opened a tremendous fire on the Britishtroops.

Sir George Cathcart brought up such portions of the 20th, 21st, 46th,57th, 63d, and 68th regiments as were not employed in the trenches,and occupied the ground to the right of the second division. GeneralCodrington, with part of the 7th, 23d, and 33d, took post to cover theextreme of our right attack. General Buller's brigade was to supportthe second division on the left, while Jeffrey's brigade, with the80th regiment, was pushed forward into the brushwood. The thirddivision, under Sir R. England, was held in reserve. The Duke ofCambridge, with the Guards, advanced on the right of the seconddivision to the edge of the plateau overlooking the valley of theTchernaya, Sir George Cathcart's division being on his right.

There was no manoeuvring. Each general led his men forward through themist and darkness against an enemy whose strength was unknown, andwhose position was only indicated by the flash of his guns and thesteady roll of his musketry. It was a desperate strife betweenindividual regiments and companies scattered and broken in the thickbrushwood, and the dense columns of gray-clad Russians, who advancedfrom the mist to meet them. Few orders were given or needed. Eachregiment was to hold the ground on which it stood, or die there.

Sir George Cathcart led his men down a ravine in front of him, but theRussians were already on the hillside above, and poured a terriblefire into the 63d. Turning, he cheered them on, and led them back upthe hill; surrounded and enormously outnumbered, the regimentssuffered terribly on their way back, Sir George Cathcart and many ofhis officers and vast numbers of the men being killed. The 88th weresurrounded, and would have been cut to pieces, when four companies ofthe 77th charged the Russians, and broke a way of retreat for theircomrades.

The Guards were sorely pressed; a heavy Russian column bore down uponthem, and bayonet to bayonet, the men strove fiercely with their foes.The ammunition failed, but they still clung to a small, unarmedbattery called the Sand-bag battery, in front of their portion, andwith volleys of stones tried to check their foes. Fourteen officersand half the men were down, and yet they held the post till anotherRussian column appeared in their rear. Then they fell back, but,reinforced by a wing of the 20th, they still opposed a resolute frontto the Russians.

Not less were the second division pressed; storms of shot and bulletsswept through them, column after column of grey-clad Russians surgedup the hill and flung themselves upon them; but, though sufferingterribly, the second division still held their ground. The 41st waswell-nigh cut to pieces, the 95th could muster but sixty-four bayonetswhen the fight was over, and the whole division, when paraded when theday was done, numbered but 800 men.

But this could not last. As fast as one assault was repulsed, freshcolumns of the enemy came up the hill to the attack, our ammunitionwas failing, the men exhausted with the struggle, and the day waswell-nigh lost when, at nine o'clock, the French streamed over thebrow of the hill on our right in great force, and fell upon the flankof the Russians. Even now the battle was not won. The Russians broughtup their reserves, and the fight still raged along the line. Foranother three hours the struggle went on, and then, finding that eventhe overwhelming numbers and the courage with which their men foughtavailed not to shake the defence, the Russian generals gave up theattack, and the battle of Inkerman was at an end.

On the Russian side some 35,000 men were actually engaged, withreserves of 15,000 more in their rear; while the British, who forthree hours withstood them, numbered but 8500 bayonets. Seven thousandfive hundred of the French took part in the fight. Forty-four Britishofficers were killed, 102 wounded; 616 men killed, 1878 wounded. TheFrench had fourteen officers killed, and thirty-four wounded; 118 menkilled, 1299 wounded. These losses, heavy as they were, were yet smallby the side of those of the Russians. Terrible, indeed, was thedestruction which the fire of our men inflicted upon the dense massesof the enemy. The Russians admitted that they lost 247 officers killedand wounded, 4076 men killed, 10,162 wounded. In this battle theBritish had thirty-eight, the French eighteen guns engaged. TheRussians had 106 guns in position.

Jack Archer and his comrades were still in bed, when the firstdropping shots, followed by a heavy roll of musketry, announced thatthe Russians were upon them. Accustomed to the roar or guns, theyslept on, till Tom Hammond rushed into the tent.

"Get up, gentlemen, get up. The Russian army has climbed up the hill,and is attacking us like old boots. The bugles are sounding the alarmall over the camps."

In an instant the lads were out of bed, and their dressing took themscarce a minute.

"I can't see ten yards before me," Jack said, as he rushed out. "ByJove, ain't they going it!"

Every minute added to the din, till the musketry grew into onetremendous roar, above which the almost unbroken roll of the cannoncould scarce by heard. Along the whole face of the trenches thebatteries of the allies joined in the din; for it was expected thatthe Russians would seize the opportunity to attack them also.

In a short time the fusillade of musketry broke out far to the left,and showed that the Russians were there attacking the French lines.The noise was tremendous, and all in camp were oppressed by the soundwhich told of a mighty conflict raging, but of which they could seeabsolutely nothing.

"This is awful," Jack said. "Here they are pounding away at eachother, and we as much out of it as if we were a thousand miles away.Don't I wish Captain Peel would march us all down to help!"

But in view of the possible sortie, it would have been dangerous todetach troops from their places on the trenches and batteries, andthe sailors had nothing to do but to wait, fuming over their forcedinaction while a great battle was raging close at hand. Overhead theRussian balls sang in swift succession, sometimes knocking down atent, sometimes throwing masses of earth into the air, sometimesbursting with a sharp detonation above them; and all this time therain fell, and the mist hung like a veil around them. Presently amounted officer rode into the sailor's camp.

"Where am I?" he said. "I have lost my way."

"This is the marine camp." Captain Peel said, stepping forward to himas he drew rein. "How is the battle going, sir?"

"Very badly, I'm afraid. We are outnumbered by five to one. Our menare fighting like heroes, but they are being fairly borne down bynumbers. The Russians have got a tremendous force of artillery on tothe hills, which we thought inaccessible to guns. There has been grosscarelessnes

s on our part, and we are paying for it now. I am lookingfor the third division camp; where is it?"

"Straight ahead, sir; but I think they have all gone forward. We heardthem tramping past in the mist."

"I am ordered to send every man forward; every musket is of value. Howmany men have you here in case you are wanted?"

"We have only fifty," Captain Peel said. "The rest are all in thebattery, and I dare not move forward without absolute orders, as wemay be wanted to reinforce them, if the enemy makes a sortie."

The officer rode on, and the sailors stood in groups behind the lineof piled muskets, ready for an instant advance, if called upon.

Another half-hour passed, and the roll of fire continued unabated.

"It is certainly nearer than it was," Captain Peel said to Mr.Hethcote. "No orders have come, but I will go forward myself and seewhat is doing. Even our help, small as it is, may be useful at somecritical point. I will take two of the midshipmen with me, and willsend you back news of what is doing."

"Mr. Allison and Mr. Archer, you will accompany Captain Peel," Mr.Hethcote said.

And the two youngsters, delighted at being chosen, prepared to startat once.

"If they send up for reinforcements from the battery, Mr. Hethcote,you will move the men down at once, without waiting for me. Take everyman down, even those on duty as cooks. There is no saying how hard wemay be pressed."

Followed by the young midshipmen, Captain Peel strode away through themist, which was now heavy with gunpowder-smoke. They passed throughthe camp of the second division, which was absolutely deserted, exceptthat there was a bustle round the hospital marquees, to which a stringof wounded, some carried on stretchers, some making their waypainfully on foot, was flowing in.

Many of the tents had been struck down by the Russian shot; blackheaps showed where others had been fired by the shell. Dimly ahead,when the mist lifted, could be seen bodies of men, while on a distantcrest were the long lines of Russian guns, whose fire swept theBritish regiments.

"I suppose these regiments are in reserve?" Jack said, as he passedsome of Sir R. England's division, lying down in readiness to move tothe front when required, most of the battalions having already goneforward to support the troops who were most pressed.

Presently Captain Peel paused on a knoll, close to a body of mountedofficers.

"There's Lord Raglan," Allison said, nudging Jack. "That's theheadquarter staff."

At that moment a shell whizzed through the air, and exploded in thecentre of the group.

Captain Gordon's horse was killed, and a portion of the shell carriedaway the leg of General Strangeway. The old general never moved, butsaid quietly,--

"Will any one be kind enough to lift me off my horse?"

He was laid down on the ground, and presently carried to the rear,where an hour afterwards he died.

Jack and his comrades, who were but a few yards away, felt strange andsick, for it was the first they had seen of battle close at hand. LordRaglan, with his staff, moved slowly forward. Captain Peel asked if heshould bring up his sailors, but was told to hold them in reserve, asthe force in the trenches had already been fearfully weakened.

"Stay here," Captain Peel said to the midshipmen. "I shall go forwarda little, but do you remain where you are until I return. Just liedown behind the crest. You will get no honor if you are hit here."

The lads were not sorry to obey, for a perfect hail of bullets waswhistling through the air. The mist had lifted still farther, and theycould obtain a sight of the whole line along which the struggle wasraging, scarce a quarter of a mile in front of them. Sometimes theremnants of a regiment would fall back from the front, when a freshbattalion from the reserves came up to fill its place, then formingagain, would readvance into the thick belt of smoke which marked wherethe conflict was thickest. Sometimes above the roll of musketry wouldcome the sharp rattle which told of a volley by the British rifles.

Well was it that two out of the three divisions were armed withMinies, for these created terrible havoc among the Russians, whosesmooth-bores were no match for these newly-invented weapons.

With beating hearts the boys watched the conflict, and could mark thatthe British fire grew feebler, and in some places ceased altogether,while the wild yells of the Russians rose louder as they pressedforward exultingly, believing that victory lay within their grasp.

"Things look very bad, Jack," Allison said. "Ammunition is evidentlyfailing, and it is impossible for our fellows to hold out much longeragainst such terrible odds. What on earth are the French doing allthis time? Our fellows have been fighting single-handed for the lastthree hours. What in the world can they be up to?"

And regardless of the storm of bullets, he leaped to his feet andlooked round.

"Hurrah, Jack! Here they come, column after column. Ten more minutesand they'll be up. Hurry up, you lubbers," he shouted in hisexcitement; "every minute is precious, and you've wasted time enough,surely. By Jove, they're only just in time. There are the Guardsfalling back. Don't you see their bearskins?"

"They are only just in time," Jack agreed, as he stood beside hiscomrade. "Another quarter of an hour and they would have had to beginthe battle afresh, for there would have been none of our fellows left.Hurrah! hurrah!" he cried, as, with a tremendous volley and a ringingshout, the French fell upon the flank of the Russians.

The lads had fancied that before that onslaught the Russians must havegiven way at once. But no. Fresh columns of troops topped the hill,fresh batteries took the place of those which had suffered mostheavily by the fire of our guns, and the fight raged as fiercely asever. Still, the boys had no fear of the final result. The French werefairly engaged now, and from their distant camps fresh columns oftroops could be seen streaming across the plateau.

Upon our allies now fell the brunt of the fight, and the British,wearied and exhausted, were able to take a short breathing-time. Then,with pouches refilled and spirits heightened, they joined in the frayagain, and, as the fight went on, the cheers of the British and theshouts of the French rose louder, while the answering yell of theRussians grew fainter and less frequent. Then the thunder of musketrysensibly diminished. The Russian artillery-men were seen to bewithdrawing their guns, and slowly and sullenly the infantry fell backfrom the ground which they had striven so hard to win.

It was a heavy defeat, and had cost them 15,000 men; but, at least, ithad for the time saved Sebastopol; for, with diminished forces, theBritish generals saw that all hopes of carrying the place by assaultbefore the winter were at an end and that it would need all theireffort to hold their lines through the months of frost and snow whichwere before them.

When the battle was over, Captain Peel returned to the point where hehad left the midshipmen, and these followed him back to the camp,where, however, they were not to stay, for every disposable man was atonce ordered out to proceed with stretchers to the front to bring inwounded.

Terrible was the sight indeed. In many places the dead lay thicklypiled on the ground, and the manner in which Englishmen, Russians, andFrenchmen lay mixed together showed how the tide of battle had ebbedand flowed, and how each patch of ground had been taken and retakenagain and again. Here Russians and grenadiers lay stretched side byside, sometimes with their bayonets still locked in each other'sbodies. Here, where the shot and shell swept most fiercely, lay thedead, whose very nationality was scarcely distinguishable, so torn andmutilated were they.

Here a French Zouave, shot through the legs, was sitting up,supporting on his breast the head of his dying officer. A little wayoff, a private of the 88th, whose arm had been carried away, besoughtthe searchers to fill and light his pipe for him, and to take themusket out of the hand of a wounded Russian near, who, he said, hadthree times tried to get it up to fire at him as he lay.

In other cases, Russians and Englishmen had already laid aside theirenmity, and were exchanging drinks from their water-bottles.

Around the sand-bag battery, which the Guards had held, the de

ad laythicker than elsewhere on the plateau; while down in the ravine whereCathcart had led his men, the bodies of the 63d lay heaped together.The sailors had, before starting, fill their bottles with grog, andthis they administered to friend and foe indiscriminately, saving manya life ebbing fast with the flow of blood. The lads moved here andthere, searching for the wounded among the dead, awed and sobered bythe fearful spectacle. More than one dying message was breathed intotheir ears; more than one ring or watch given to them to send to dearones at home. All through the short winter day they worked, aided bystrong parties of the French who had not been engaged; and it was asatisfaction to know that, when night fell, the greater portion of thewounded, British and French, had been carried off the field. As forthe Russians, those who fell on the plateau received equal care withthe allies; but far down among the bushes that covered the hillsidelay hundreds of wounded wretches whom no succor, that day at least,could be afforded.

The next day the work of bringing in the Russian wounded wascontinued, and strong fatigue parties were at work, digging greatpits, in which the dead were laid those of each nationality being keptseparate.

The British camps, on the night after Inkerman, afforded a strongcontrast to the scene which they presented the night before. No merrylaugh arose from the men crouched round the fires; no song soundedthrough the walls of the tents. There was none of the joy and triumphof victory; the losses which had been suffered were so tremendous asto overpower all other feeling. Of the regiments absolutely engaged,fully one-half had fallen; and the men and officers chatted in hushedvoices over the good fellows who had gone, and of the chances of thosewho lay maimed and bleeding in the hospital tents.

To his great relief, Jack had heard, early in the afternoon, that the33d had not been hotly engaged, and that his brother was unwounded.The two young officers of the 30th, who had, a few hours before, beenspending the evening so merrily in the tent, had both fallen, as hadmany of the friends in the brigade of Guards whose acquaintance he hadmade on board the "Ripon," and in the regiments which, being encampednear by the sailors, he had come to know.

Midshipmen are not given to moralizing, but it was not in human naturethat the lads, as they gathered in their tent that evening, should nottalk over the sudden change which so few hours had wrought. The futureof the siege, too, was discussed, and it was agreed that they werefixed where they were for the winter.

The prospect was a dreary one, for if they had had so many discomfortsto endure hitherto, what would it be during the next four months onthat bleak plateau? For themselves, however, they were indifferent inthis respect, as it was already known the party on shore would beshortly relieved.

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

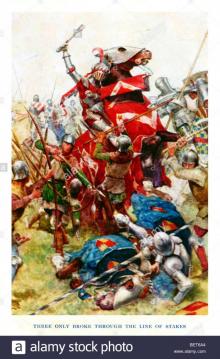

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates