- Home

- G. A. Henty

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California Read online

Produced by David Edwards, Emmy and the Online DistributedProofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file wasproduced from images generously made available by TheInternet Archive)

CAPTAIN BAYLEY'S HEIR

A TALE OF THE GOLD FIELDS OF CALIFORNIA.

BY G. A. HENTY

CAPTAIN BAYLEY'S HEIR.

CAPTAIN BAYLEY HEARS STARTLING NEWS.]

CAPTAIN BAYLEY'S HEIR:

A TALE OF THE GOLD FIELDS OF CALIFORNIA.

BY

G. A. HENTY,

Author of "With Clive in India;" "Facing Death;" "For Name and Fame;""True to the Old Flag;" "A Final Beckoning;" &c.

_WITH TWELVE FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS BY H. M. PAGET._

NEW YORK SCRIBNER AND WELFORD 743 & 745 BROADWAY.

CONTENTS.

Chap. Page

I. WESTMINSTER! WESTMINSTER! 9

II. A COLD SWIM, 25

III. A CRIPPLE BOY, 42

IV. AN ADOPTED CHILD, 58

V. A TERRIBLE ACCUSATION, 75

VI. AT NEW ORLEANS, 92

VII. ON THE MISSISSIPPI, 107

VIII. STARTING FOR THE WEST, 127

IX. ON THE PLAINS, 154

X. A BUFFALO STORY, 173

XI. HOW DICK LOST HIS SCALP, 186

XII. THE ATTACK ON THE CARAVAN, 206

XIII. AT THE GOLD-FIELDS, 223

XIV. CAPTAIN BAYLEY, 238

XV. THE MISSING HEIR, 253

XVI. JOHN HOLL, DUST CONTRACTOR, 268

XVII. THE LONELY DIGGERS, 285

XVIII. A DREAM VERIFIED, 306

XIX. STRIKING IT RICH, 324

XX. A MESSAGE FROM ABROAD, 341

XXI. HAPPY MEETINGS, 360

XXII. CLEARED AT LAST, 374

ILLUSTRATIONS.

Page

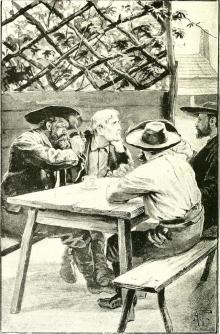

CAPTAIN BAYLEY HEARS STARTLING NEWS, _Frontis._ 262

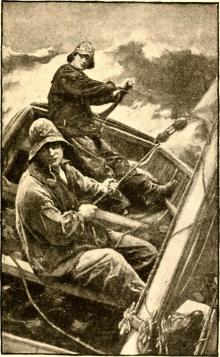

THE RESCUE FROM THE SERPENTINE, 32

THE BREAK-UP OF THE CHARTIST MEETING, 72

FRANK'S VISIT TO MR. HIRAM LITTLE'S OFFICE, 101

A FLOOD ON THE MISSISSIPPI, 125

A DEER-HUNT ON THE PRAIRIE, 162

THE ESCAPE OF THE CAPTAIN'S DAUGHTER, 195

DICK AND FRANK ELUDE THE INDIANS, 227

THE SICK FRIEND IN THE MINING CAMP, 296

GOLD-WASHING--A GOOD DAY'S WORK, 329

THE ATTACK ON THE GOLD ESCORT, 338

MEETING OF CAPTAIN BAYLEY AND MR. ADAMS, 352

CAPTAIN BAYLEY'S HEIR.

CHAPTER I.

WESTMINSTER! WESTMINSTER!

A CRIPPLE boy was sitting in a box on four low wheels, in a little roomin a small street in Westminster; his age was some fifteen or sixteenyears; his face was clear-cut and intelligent, and was altogether freefrom the expression either of discontent or of shrinking sadness sooften seen in the face of those afflicted. Had he been sitting on achair at a table, indeed, he would have been remarked as a handsome andwell-grown young fellow; his shoulders were broad, his arms powerful,and his head erect. He had not been born a cripple, but had beendisabled for life, when a tiny child, by a cart passing over his legsabove the knees. He was talking to a lad a year or so younger thanhimself, while a strong, hearty-looking woman, somewhat past middle age,stood at a wash-tub.

"What is all that noise about?" the cripple exclaimed, as an uproar washeard in the street at some little distance from the house.

"Drink, as usual, I suppose," the woman said.

The younger lad ran to the door.

"No, mother; it's them scholars a-coming back from cricket. Ain't therea fight jist!"

The cripple wheeled his box to the door, and then taking a pair ofcrutches which rested in hooks at its side when not wanted, swunghimself from the box, and propped himself in the doorway so as tocommand a view down the street.

It was indeed a serious fight. A party of Westminster boys, on their wayback from their cricket-ground in St. Vincent's Square, had beenattacked by the "skies." The quarrel was an old standing one, but hadbroken out afresh from a thrashing which one of the older lads hadadministered on the previous day to a young chimney-sweep about his ownage, who had taken possession of the cricket-ball when it had beenknocked into the roadway, and had, with much strong language, refused tothrow it back when requested.

The friends of the sweep determined to retaliate upon the following day,and gathered so threateningly round the gate that, instead of the boyscoming home in twos and threes, as was their wont, when playtimeexpired, they returned in a body. They were some forty in number, andvaried in age from the little fags of the Under School, ten or twelveyears old, to brawny muscular young fellows of seventeen or eighteen,senior Queen's Scholars, or Sixth Form town boys. The Queen's Scholarswere in their caps and gowns, the town boys were in ordinary attire, afew only having flannel cricketing trousers.

On first leaving the field they were assailed only by volleys of abuse;but as they made their way down the street their assailants grew bolder,and from words proceeded to blows, and soon a desperate fight wasraging. In point of numbers the "skies" were vastly superior, and manyof them were grown men; but the knowledge of boxing which almost everyWestminster boy in those days possessed, and the activity and quicknessof hitting of the boys, went far to equalise the odds.

Pride in their school, too, would have rendered it impossible for any toshow the white feather on such an occasion as this, and with the youngerboys as far as possible in their centre, the seniors faced theiropponents manfully. Even the lads of but thirteen and fourteen years oldwere not idle. Taking from the fags the bats which several of the latterwere carrying, they joined in the conflict, not striking at theiropponents' heads, but occasionally aiding their seniors, when attackedby three or four at once, by swinging blows on their assailant's shins.

Man after man among the crowd had gone down before the blows straightfrom the shoulder of the boys, and many had retired from the contestwith faces which would for many days bear marks of the fight; but theirplaces were speedily filled up, and the numbers of the assailants grewstronger every minute.

"How well they fight!" the cripple exclaimed. "Splendid! isn't it,mother? But there are too many against them. Run, Evan, quick, down toDean's Yard; you are sure to find some of them playing at racquets inthe Little Yard, tell them that the boys coming home from cricket havebeen attacked, and that unless help comes they will be terribly knockedabout."

Evan dashed off at full speed. Dean's Yard was but a few minutes' rundistant. He dashed through the little archway into the yard, down theside, and then in at another archway into Little Dean's Yard, where someelder boys were playing at racquets. A fag was picking up the balls, andtwo or three others were standing at the top of the steps of the twoboarding-houses.

"If you please, sir," Evan said, running up to one of theracquet-players, "there is just a row going on; they are all pitchinginto the scholars on their way back from Vincent Square, and if youdon't send help they will get it nicely, though they are all fightinglike bricks."

"Here, all of you," the lad he addressed shouted to the others; "ourfellows are attacked by the 'skies' on their way back from fields. Runup College, James; the fellows from the water have come back." Then heturned to the boys on the steps, "Bring all the fellows out quick; the'skies' are attacking us on the way back from the fields. Don't let themwait a moment."

It was lucky that the boys who had been on the water in the two eights,the six, and the fours, had returned, or at that hour there would havebeen few in the boarding-houses or up College. Ere a minute had elapsedthese, with a few others who had been kept off field and water fromindisposition, or other causes, came pouring out at the summons--a bodysome thirty strong, of whom fully half were big boys. They dashed out ofthe gate in a body, and made their way to the scene of the conflict.They were but just in time; the compact group of the boys had beenbroken up, and every one now was fighting for himself.

They had made but little progress towards the school since Evan hadstarted, and the fight was now raging opposite his house. The cripplewas almost crying with excitement and at his own inability to join inthe fight going on. His sympathies were wholly with "the boys," towardswhose side he was attached by the disparity of their numbers compared tothose of their opponents, and by the coolness and resolution with whichthey fought.

"Just look at those two, mother--those two fighting back to back. Isn'tit grand! There! there is another one down; that is the fifth I havecounted. Don't they fight cool and steady? and they almost look smiling,though the odds against them are ten to one. O mother, if I could but goto help them!"

Mrs. Holl herself was not without sharing his excitement. Several timesshe made sorties from her doorstep, and seized more than one hulkingfellow in the act of pummelling a youngster half his size, and shook himwith a vigour which showed that constant exercise at the wash-tub hadstrengthened her arms.

"Yer ought to be ashamed of yerselves, yer ought; a whole crowd of yerpitching into a handful o' boys."

But her remonstrances were unheeded in the din,--which, however, wasraised entirely by the assailants, the boys fighting silently, save whenan occasional shout of "Hurrah, Westminster!" was raised. Presently Evandashed through the crowd up to the door.

"Are they coming, Evan?" the cripple asked eagerly.

"Yes, 'Arry; they will be 'ere in a jiffy."

A half-minute later, and with shouts of "Westminster! Westminster!" thereinforcement came tearing up the street.

Their arrival in an instant changed the face of things. The "skies" fora moment or two resisted; but the muscles of the eight--hardened by thetraining which had lately given them victory over Eton in their annualrace--stood them in good stead, and the hard hitting of the "water" soonbeat back the lately triumphant assailants of "cricket." The united bandtook the offensive, and in two or three minutes the "skies" were in fullflight.

"We were just in time, Norris," one of the new-comers said to the talllad in cricketing flannels whose straight hitting had particularlyattracted the admiration of Harry Holl.

"Only just," the other said, smiling; "it was a hot thing, and a prettysight we shall look up School to-morrow. I shall have two thunderingblack eyes, and my mouth won't look pretty for a fortnight; and, by thelook of them, most of the others have fared worse. It's the biggestfight we have had for years. But I don't think the 'skies' willinterfere with us again for some time, for every mark we've got they'vegot ten. Won't there be a row in School to-morrow when Litter sees thathalf the Sixth can't see out of their eyes."

Not for many years had the lessons at Westminster been so badly preparedas they were upon the following morning--indeed, with the exception ofthe half and home-boarders, few of whom had shared in the fight, not asingle boy, from the Under School to the Sixth, had done an exercise orprepared a lesson. Study indeed had been out of the question, for allwere too excited and too busy talking over the details of the battle tobe able to give the slightest attention to their work.

Many were the tales of feats of individual prowess; but all who hadtaken part agreed that none had so distinguished themselves as FrankNorris, a Sixth Form town boy, and captain of the eight--who, for awonder had for once been up at fields--and Fred Barkley, a senior inthe Sixth. But, grievous and general as was the breakdown in lessonsnext day, no impositions were set; the boarding-house masters, Richardsand Sargent, had of course heard all about it at tea-time, as had Johns,who did not himself keep a boarding-house, but resided at Carr's, theboarding-house down by the great gate.

These, therefore, were prepared for the state of things, and contentedthemselves by ordering the forms under their charge to set to work withtheir dictionaries and write out the lessons they should have prepared.The Sixth did not get off so easily. Dr. Litter, in his lofty solitudeas head-master, had heard nothing of what had passed; nor was it untilthe Sixth took their places in the library and began to construe thathis attention was called to the fact that something unusual hadhappened. But the sudden hesitation and blundering of the first "puton," and the inability of those next to him to correct him, were toomarked to be passed over, and he raised his gold-rimmed eye-glasses tohis eyes and looked round.

Dr. Litter was a man standing some six feet two in height, stately inmanner, somewhat sarcastic in speech,--a very prodigy in classicallearning, and joint author of the great treatise _On the Uses of theGreek Particle_. Searchingly he looked from face to face round thelibrary.

"I cannot," he said, with a curl of his upper lip, and the cold andsomewhat nasal tone which set every nerve in a boy's body twitching whenhe heard it raised in reproof, "I really cannot congratulate you on yourappearance. I thought that the Sixth Form of Westminster was composed ofgentlemen, but it seems to me now as if it consisted of a number ofsingularly disreputable-looking prize-fighters. What does all thismean, Williams?" he asked, addressing the captain; "your face appears tohave met with better usage than some of the others."

"It means, sir," Williams said, "that as the party from fields werecoming back yesterday evening, they were attacked by the 'skies,'--Imean by the roughs--and got terribly knocked about. When the news cameto us I was up College, and the fellows had just come back from thewater, so of course we all sallied out to rescue them."

"Did it not occur to you, Williams, that there is a body called thepolice, whose duty it is to interfere in disgraceful uproars of thissort?"

"If we had waited for the police, sir," Williams said, "half the Schoolwould not have been fit to take their places in form again before theend of the term."

"It does not appear to me," Dr. Litter said, "that a great many of themare fit to take their places at present. I can scarcely see Norris'seyes; and I suppose that boy is Barkley, as he sits in the place that heusually occupies, otherwise, I should not have recognised him; andSmart, Robertson, and Barker and Barret are nearly as bad. I suppose youfeel satisfied with yourselves, boys, and consider that this sort ofthing is creditable to you; to my mind it is simply disgraceful. There!I don't want to hear any more at present; I suppose the whole School isin the same state. Those of you who can see had better go back to Schooland prepare your Demosthenes; those who cannot had best go back to theirboarding-houses, or up College, and let the doctor be sent for to see ifanything can be done for you."

The doctor had indeed already been sent for, for some seven or eight ofthe younger boys had been so seriously knocked about and kicked thatthey were unable to leave their beds. For the rest a doctor could donothing. Fights were not uncommon at Westminster in those days, but thenumber of orders for beef-steaks which the nearest butcher had receivedon the previous evening had fairly astonished him. Indeed, had it notbeen for the prompt application of these to their faces, very few of theparty from the fields would have been able to find their way up Schoolunless they had been led by their comrades.

At Westminster there was an hour's school before breakfast, and whennine o'clock struck, and the boys poured out, Dr. Litter and hisunder-masters held council together.

"This is a disgrace

ful business!" Dr. Litter said, looking, as was hiswont, at some distant object far over the heads of the others.

There was a general murmur of assent.

"The boys do not seem to have been much to blame," Mr. Richardssuggested in the cheerful tone habitual to him. "From what I can hear itseems to have been a planned thing; the people gathered round the gatesbefore they left the fields and attacked them without any provocation."

"There must have been some provocation somewhere, Mr. Richards, if notyesterday, then the day before, or the day before that," Dr. Littersaid, twirling his eye-glass by the ribbon. "A whole host of people donot gather to assault forty or fifty boys without provocation. This sortof thing must not occur again. I do not see that I can punish one boywithout punishing the whole School; but, at any rate, for the next weekfields must be stopped. I shall write to the Commissioner of Police,asking that when they again go to Vincent Square some policemen may beput on duty, not of course to accompany them, but to interfere at onceif they see any signs of a repetition of this business. I shall requestthat, should there be any fighting, those not belonging to the Schoolwho commit an assault may be taken before a magistrate; my own boys Ican punish myself. Are any of the boys seriously injured, do you think?"

"I hope not, sir," Mr. Richards said; "there are three or four in myhouse, and there are ten at Mr. Sargent's, and two at Carr's, who havegone on the sick list. I sent for the doctor, and he may have seen themby this time; they all seemed to have been knocked down and kicked."

"There are four of the juniors at College in the infirmary," Mr. Wire,who was in special charge of the Queen's Scholars, put in. "I had notheard about it last night, and was in ignorance of what had taken placeuntil the list of those who had gone into the infirmary was put into myhands, and then I heard from Williams what had taken place."

"It is very unpleasant," Dr. Litter said, in a weary tone of voice--asif boys were a problem far more difficult to be mastered than any thatthe Greek authors afforded him--"that one cannot trust boys to keep outof mischief for an hour. Of course with small boys this sort of thing isto be expected; but that young fellows like Williams and the otherseniors, and the Sixth town boys, who are on the eve of going up to theUniversities, should so far forget themselves is very surprising."

"But even at the University, Doctor Litter," Mr. Richards said, with apassing thought of his own experience, "town and gown rows take place."

"All the worse," Dr. Litter replied, "all the worse. Of course there arewild young men at the Universities." Dr. Litter himself, it is scarcelynecessary to say, had never been wild, the study of the Greek particleshad absorbed all his thoughts. "Why," he continued, "young men shouldcondescend to take part in disgraceful affrays of this kind passes myunderstanding. Mr. Wire, you will inform Williams that for the rest ofthe week no boy is to go to fields."

So saying, he strode off in the direction of his own door, next to thearchway, for the conversation had taken place at the foot of the stepsleading into School from Little Dean's Yard. There was some grumblingwhen the head-master's decision was known; but it was, nevertheless,felt that it was a wise one, and that it was better to allow thefeelings to calm down before again going through Westminster betweenDean's Yard and the field, for not even the most daring would have caredfor a repetition of the struggle.

Several inquiries were made as to the lad who had brought the news ofthe fight, and so enabled the reinforcements to arrive in time; and hadhe been discovered a handsome subscription would have been got up toreward his timely service, but no one knew anything about him.

The following week, when cricket was resumed, no molestation wasoffered. The better part of the working-classes who inhabited theneighbourhood were indeed strongly in favour of the "boys," and liked tosee their bright young faces as they passed home from their cricket;the pluck too with which they had fought was highly appreciated, and sostrong a feeling was expressed against the attack made upon them, thatthe rough element deemed it better to abstain from further interruption,especially as there were three or four extra police put upon the beat atthe hours when the "boys" went to and from Vincent Square.

It was, however, some time before the "great fight" ceased to be asubject of conversation among the boys. At five minutes to ten on themorning when Dr. Litter had put a stop to fields, two of the youngerboys--who were as usual, just before school-time, standing in thearchway leading into Little Dean's Yard to warn the School of theissuing out of the head-master--were talking of the fight of the eveningbefore; both had been present, having been fagging out at cricket fortheir masters.

"I wonder which would lick, Norris or Barkley. What a splendid fight itwould be!"

"You will never see that, Fairlie, for they are cousins and greatfriends. It would be a big fight, and I expect it would be a draw. Iknow who I should shout for."

"Oh, of course, we should all be for Norris, he is such a jolly fellow;there is no one in the School I would so readily fag for. Instead ofsaying, 'Here, you fellow, come and pick up balls,' or, 'Take my bat upto fields,' he says, 'I say, young Fairlie, I wish you would come andpick up balls for a bit, and in a quarter of an hour you can call someother Under School boy to take your place,' just as if it were a favour,instead of his having the right to put one on if he pleased. I shouldlike to be his fag: and he never allows any bullying up at Richards'. Iwish we had him at Sargent's."

"Yes, and Barkley is quite a different sort of fellow. I don't know thathe is a bully, but somehow he seems to have a disagreeable way with him,a cold, nasty, hard sort of way; he walks along as if he never noticedthe existence of an Under School boy, while Norris always has a pleasantnod for a fellow."

"Here's Litter."

At this moment a door in the wall under the archway opened, and thehead-master appeared. As he came out the five or six small boys standinground raised a tremendous shout of "Litter's coming." A shout so loudthat it was heard not only in College and the boarding-houses in LittleDean's Yard, but at Carr's across by the archway, and even atSutcliffe's shop outside the Yard, where some of the boys werepurchasing sweets for consumption in school. A fag at the door of eachof the boarding-houses took up the cry, and the boys at once camepouring out.

The Doctor, as if unconscious of the din raised round him, walked slowlyalong half-way to the door of the School; here he was joined by theother masters, and they stood chatting in a group for about two minutes,giving ample time for the boys to go up School, though those fromCarr's, having much further to go, had to run for it, and notunfrequently had to rush past the masters as the latter mounted the widestone steps leading up to the School.

The School was a great hall, which gave one the idea that it was almostcoeval with the abbey to which it was attached, although it was notbuilt until some hundreds of years later. The walls were massive, and ofgreat height, and were covered from top to bottom with the painted namesof old boys, some of which had been there, as was shown by the datesunder them, close upon a hundred years. The roof was supported on greatbeams, and both in its proportions and style the School was a copy insmall of the great hall of Westminster.

At the furthermost end from the door was a semicircular alcove, known asthe "Shell," which gave its name to the form sitting there. On bothsides ran rows of benches and narrow desks, three deep, raised one abovethe other. On the left hand on entering was the Under School, and,standing on the floor in front of it, was the arm-chair of Mr. Wire.Next came the monitor's desk, at which the captain and two monitors sat.In an open drawer in front of the table were laid the rods, which werenot unfrequently called into requisition. Extending up to the end werethe seats of the Sixth. The "Upper Shell" occupied the alcove; the"Under Shell" were next to them, on the further benches on theright-hand side. Mr. Richards presided over the "Shell." Mr. Sargenttook the Upper and Under Fifth, who came next to them, and "Johnny," asMr. Johns was called, looked after the two Fourths, who occupied bencheson the right hand of the door.

By the time the masters entered th

e School all the boys were in theirplaces. The doors were at once shut, then the masters knelt on one kneein a line, one behind the other, in order of seniority, and the JuniorQueen's Scholar whose turn it was knelt in front of them, and in a loudtone read the Lord's Prayer in Latin. Then the masters proceeded totheir places, and school began, the names of all who came in late beingtaken down to be punished with impositions.

So large and lofty was the hall, that the voices were lost in itsspace, and the forms were able to work without disturbing each other anymore than if they had been in separate rooms. The Sixth only were heardapart, retiring into the library with the Doctor. His seat, when inschool, was at a table in the centre of the hall, near the upper end.

Thus Westminster differed widely from the great modern schools, withtheir separate class-rooms and lecture-rooms. Discipline was not verystrict. When a master was hearing one of the forms under him the otherwas supposed to be preparing its next lessons, but a buzz of quiet talkwent on steadily. Occasionally, once or twice a week perhaps, a boywould be seen to go up from one of the lower forms with a note in hishand to the head-master; then there was an instant pause in the talking.

Dr. Litter would rise from his seat, and a monitor at once brought him arod. These instruments of punishment were about three feet six incheslong; they were formed of birch twigs, very tightly bound together, andabout the thickness of the handle of a bat; beyond this handle some tenor twelve twigs extended for about eighteen inches. The Doctor seldommade any remark beyond giving the order, "Hold out your hand."

The unfortunate to be punished held out his arm at a level with hisshoulder, back uppermost. Raising his arm so that the rod fell almoststraight behind his back, Dr. Litter would bring it down, stroke afterstroke, with a passionless and mechanical air, but with a sweeping forcewhich did its work thoroughly. Four cuts was the normal number, but ifit was the third time a boy had been sent up during the term he wouldget six. But four sufficed to swell the back of the hand, and cover itwith narrow weals and bruises. It was of course a point of honour thatno sound should be uttered during punishment. When it was over theDoctor would throw the broken rod scornfully upon the ground and returnto his seat. The Junior then carried it away and placed a fresh one uponthe desk.

The rods were treated with a sort of reverence, for no Junior Queen'sScholar ever went up or down school for any purpose without first goingover to the monitor's table and lightly touching the rod as he passed.

Such was school at Westminster forty years since, and it has but littlechanged to the present day.

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

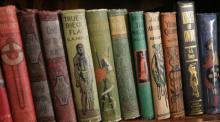

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

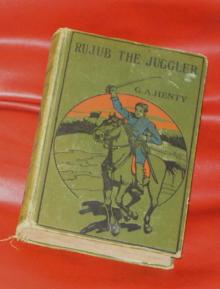

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

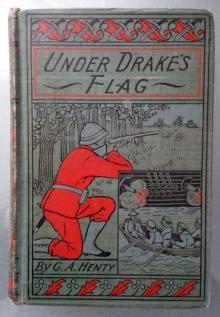

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

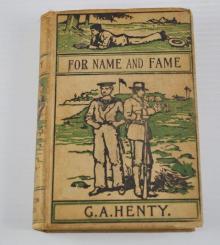

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates