- Home

- G. A. Henty

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Page 14

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Read online

Page 14

CHAPTER XI.

THE HAU-HAUS.

The next three months made a great change in the appearance of TheGlade. Three or four plots of gay flowers cut in the grass between thehouse and the river gave a brightness to its appearance. The house wasnow covered as far as the roof with greenery, and might well have beenmistaken for a rustic bungalow standing in pretty grounds on the banksof the Thames. Behind, a large kitchen-garden was in full bearing. Itwas surrounded by wire network to keep out the chickens, ducks, andgeese, which wandered about and picked up a living as they chose,returning at night to the long low shed erected for them at somedistance from the house, receiving a plentiful meal on their arrival toprevent them from lapsing into an altogether wild condition.

Forty acres of land had been reploughed and sown, and the crops hadalready made considerable progress. In the more distant clearings adozen horses, twenty or thirty cows, and a small flock of a hundredsheep grazed, while some distance up the glade in which the house stoodwas the pig-sty, whose occupants were fed with refuse from the garden,picking up, however, the larger portion of their living by rooting inthe woods.

Long before Mr. and Mrs. Renshaw moved into the house, Wilfrid, whoselabours were now less severe, had paid his first visit to Mr. Atherton'shut. He was at once astonished and delighted with it. It containedindeed but the one room, sixteen feet square, but that room had beenmade one of the most comfortable dens possible. There was no flooring,but the ground had been beaten until it was as hard as baked clay, andwas almost covered with rugs and sheep-skins; a sort of divan ran roundthree sides of it, and this was also cushioned with skins. The log wallswere covered with cow-hides cured with the hair on, and from hooks andbrackets hung rifles, fishing-rods, and other articles, while horns andother trophies of the chase were fixed to the walls.

While the Renshaws had contented themselves with stoves, Mr. Athertonhad gone to the expense and trouble of having a great open fireplace,with a brick chimney outside the wall. Here, even on the hottest day,two or three logs burnt upon old-fashioned iron dogs. On the wall abovewas a sort of trophy of oriental weapons. Two very large and comfortableeasy chairs stood by the side of the hearth, and in the centre of theroom stood an old oak table, richly carved and black with age. Abook-case of similar age and make, with its shelves well filled withstandard works, stood against the one wall unoccupied by the divan.

Wilfrid stood still with astonishment as he looked in at the door, whichMr. Atherton had himself opened in response to his knock.

"Come in, Wilfrid. As I told you yesterday evening I have just gotthings a little straight and comfortable."

"I should think you had got them comfortable," Wilfrid said. "I shouldnot have thought that a log cabin could have been made as pretty asthis. Why, where did you get all the things? Surely you can never havebrought them all with you?"

"No, indeed," Mr. Atherton laughed; "the greatest portion of them areproducts of the country. There was no difficulty in purchasing theskins, the arms, and those sets of horns and trophies. Books and a fewother things I brought with me. I have a theory that people very oftenmake themselves uncomfortable merely to effect the saving of a pound ortwo. Now, I rather like making myself snug, and the carriage of allthose things did not add above five pounds to my expenses."

"But surely that table and book-case were never made in New Zealand?"

"Certainly not, Wilfrid. At the time they were made the natives of thiscountry hunted the Moa in happy ignorance of the existence of a whiterace. No, I regard my getting possession of those things as a specialstroke of good luck. I was wandering in the streets of Wellington on thevery day after my arrival, when I saw them in a shop. No doubt they hadbeen brought out by some well-to-do emigrant, who clung to them inremembrance of his home in the old country. Probably at his death hisplace came into the hands of some Goths, who preferred a clean dealtable to what he considered old-fashioned things. Anyhow, there theywere in the shop, and I bought them at once; as also those arm-chairs,which are as comfortable as anything of the kind I have ever tried. Bythe way, are you a good shot with the rifle, Wilfrid?"

"No, sir; I never fired a rifle in my life before I left England, nor ashot-gun either."

"Then I think you would do well to practise, lad; and those two men ofyours should practise too. You never can say what may come of thesenative disturbances; the rumours of the progress of this new religionamong them are not encouraging. It is quite true that the natives onthis side of the island have hitherto been perfectly peaceable, but ifthey get inoculated with this new religious frenzy there is no sayingwhat may happen. I will speak to your father about it. Not in a way toalarm him; but I will point out that it is of no use your having broughtout firearms if none of you know how to use them, and suggest that itwill be a good thing if you and the men were to make a point of firing adozen shots every morning at a mark. I shall add that he himself mightjust as well do so, and that even the ladies might find it an amusement,using, of course, a light rifle, or firing from a rest with an ordinaryrifle with light charges, or that they might practice with revolvers.Anyhow, it is certainly desirable that you and your father and the menshould learn to be good shots with these weapons. I will gladly comeover at first and act as musketry instructor."

Wilfrid embraced the idea eagerly, and Mr. Atherton on the occasion ofhis first visit to The Glade in a casual sort of way remarked to Mr.Renshaw that he thought every white man and woman in the outlyingcolonies ought to be able to use firearms, as, although they might neverbe called upon to use them in earnest, the knowledge that they could doso with effect would greatly add to their feeling of security andcomfort. Mr. Renshaw at once took up the idea and accepted the other'soffer to act as instructor. Accordingly, as soon as the Renshaws wereestablished upon their farm, it became one of the standing rules of theplace that Wilfrid and the two men should fire twelve shots at a markevery morning before starting for their regular work at the farm.

The target was a figure roughly cut out of wood, representing the sizeand to some extent the outline of a man's figure.

"It is much better to accustom yourself to fire at a mark of this kindthan to practise always at a target," Mr. Atherton said. "A man mayshoot wonderfully well at a black mark in the centre of a white square,and yet make very poor practice at a human figure with its dull shadesof colour and irregular outline."

"But we shall not be able to tell where our bullets hit," Wilfrid said;"especially after the dummy has been hit a good many times."

"It is not very material where you hit a man, Wilfrid, so that you dohit him. If a man gets a heavy bullet, whether in an arm, a leg, or thebody, there is no more fight in him. You can tell by the sound of thebullet if you hit the figure, and if you hit him you have done what youwant to. You do not need to practise at distances over three hundredyards; that is quite the outside range at which you would ever want todo any shooting, indeed from fifty to two hundred I consider the usefuldistance to practise at. If you get to shoot so well that you can withcertainty hit a man between those ranges, you may feel prettycomfortable in your mind that you can beat off any attack that might bemade on a house you are defending.

"When you have learnt to do this at the full-size figure you can put itin a bush so that only the head and shoulders are visible, as would bethose of a native standing up to fire. All this white target-work isvery well for shooting for prizes, but if troops were trained to fire atdummy figures at from fifty to two hundred yards distance, and allowedplenty of ammunition for practice and kept steadily at it, you would seethat a single company would be more than a match for a whole regimenttrained as our soldiers are."

With steady practice every morning, Wilfrid and the two young men madevery rapid progress, and at the end of three months it was very seldomthat a bullet was thrown away. Sometimes Mr. Renshaw joined them intheir practice, but he more often fired a few shots some time during theday with Marion, who became quite an enthusiast in the exercise. Mrs.Renshaw declined to practise, and sa

id that she was content to remain anon-combatant, and would undertake the work of binding up wounds andloading muskets. On Saturday afternoons, when the men left off worksomewhat earlier than usual, there was always shooting for small prizes.Twelve shots were fired by each at a figure placed in the bushes ahundred yards away, with only the head and shoulders visible. After eachhad fired, the shot-holes were counted and then filled up with mud, sothat the next marks made were easily distinguishable.

Mr. Renshaw was uniformly last. The Grimstones and Marion generally raneach other very close, each putting eight or nine of their bullets intothe figure. Wilfrid was always handicapped two shots, but as hegenerally put the whole of his ten bullets into the mark, he was in themajority of cases the victor. The shooting party was sometimes swelledby the presence of Mr. Atherton and the two Allens, who had arrived afortnight after the Renshaws, and had taken up the section of land nextbelow them. Mr. Atherton was incomparably the best shot of the party.Wilfrid, indeed, seldom missed, but he took careful and steady aim atthe object, while Mr. Atherton fired apparently without waiting to takeaim at all. Sometimes he would not even lift his gun to his shoulder,but would fire from his side, or standing with his back to the markwould turn round and fire instantaneously.

"That sort of thing is only attained by long practice," he would say inanswer to Wilfrid's exclamations of astonishment. "You see, I have beenshooting in different parts of the world and at different sorts of gamefor some fifteen years, and in many cases quick shooting is of just asmuch importance as straight shooting."

But it was with the revolver that Mr. Atherton most surprised hisfriends. He could put six bullets into half a sheet of note-paper at adistance of fifty yards, firing with such rapidity that the weapon wasemptied in two or three seconds.

"I learned that," he said, "among the cow-boys in the West. Some of themare perfectly marvellous shots. It is their sole amusement, and theyspend no inconsiderable portion of their pay on cartridges. It seems tobecome an instinct with them, however small the object at which theyfire they are almost certain to hit it. It is a common thing with themfor one man to throw an empty meat-tin into the air and for another toput six bullets in before it touches the ground. So certain are they oftheir own and each others' aim, that one will hold a halfpenny betweenhis finger and thumb for another to fire at from a distance of twentyyards, and it is a common joke for one to knock another's pipe out ofhis mouth when he is quietly smoking.

"As you see, though my shooting seems to you wonderful, I should beconsidered quite a poor shot among the cow-boys. Of course, withincessant practice such as they have I should shoot a good deal betterthan I do; but I could never approach their perfection, for the simplereason that I have not the strength of wrist. They pass their lives inriding half-broken horses, and incessant exercise and hard work hardenthem until their muscles are like steel, and they scarcely feel what toan ordinary man is a sharp wrench from the recoil of a heavily-loadedColt."

Life was in every way pleasant at The Glade. The work of breaking up theland went on steadily, but the labour, though hard, was not excessive.In the evening the Allens or Mr. Atherton frequently dropped in, andoccasionally Mr. Mitford and his daughters rode over, or the party cameup in the boat. The expense of living was small. They had an amplesupply of potatoes and other vegetables from their garden, of eggs fromtheir poultry, and of milk, butter, and cheese from their cows. Whilesalt meat was the staple of their food, it was varied occasionally bychicken, ducks, or a goose, while a sheep now and then afforded a week'ssupply of fresh meat.

Mr. Renshaw had not altogether abandoned his original idea. He hadalready learnt something of the Maori language from his studies on thevoyage, and he rapidly acquired a facility of speaking it from hisconversations with the two natives permanently employed on the farm. Oneof these was a man of some forty years old named Wetini, the other was alad of sixteen, his son, whose name was Whakapanakai, but as this namewas voted altogether too long for conversational purposes he wasre-christened Jack.

Wetini spoke but a few words of English, but Jack, who had been educatedat one of the mission schools, spoke it fluently. They, with Wetini'swife, inhabited a small hut situated at the edge of the wood, at adistance of about two hundred yards from the house. It was Mr. Renshaw'scustom to stroll over there of an evening, and seating himself by thefire, which however hot the weather the natives always kept burning, hewould converse with Wetini upon the manners and customs, the religiousbeliefs and ceremonies, of his people.

In these conversations Jack at first acted as interpreter, but it wasnot many weeks before Mr. Renshaw gained such proficiency in the tonguethat such assistance was no longer needed.

But the period of peace and tranquillity at The Glade was but a shortone. Wilfrid learnt from Jack, who had attached himself specially tohim, that there were reports among the natives that the prophet Te Uawas sending out missionaries all over the island. This statement wastrue. Te Ua had sent out four sub-prophets with orders to travel amongthe tribes and inform them that Te Ua had been appointed by an angel asa prophet, that he was to found a new religion to be called Pai Marire,and that legions of angels waited the time when, all the tribes havingbeen converted, a general rising would take place, and the Pakeha beannihilated by the assistance of these angels, after which a knowledgeof all languages and of all the arts and sciences would be bestowed uponthe Pai Marire.

Had Te Ua's instructions been carried out, and his agents travelledquietly among the tribes, carefully abstaining from all open hostilityto the whites until the whole of the native population had beenconverted, the rising when it came would have been a terrible one, andmight have ended in the whole of the white population being eitherdestroyed or forced for a time to abandon the island. Fortunately thesub-prophets were men of ferocious character. Too impatient to await theappointed time, they attacked the settlers as soon as they collectedsufficient converts to do so, and so they brought about the destructionof their leaders' plans.

These attacks put the colonists on their guard, enabled the authoritiesto collect troops and stand on the defensive, and, what was still moreimportant, caused many of the tribes which had not been converted to thePai Marire faith to range themselves on the side of the English. Notbecause they loved the whites, but because from time immemorial thetribes had been divided against each other, and their traditionalhostility weighed more with them than their jealousy with the whitesettlers.

Still, although these rumours as to the spread of the Pai Marire orHau-Hau faith reached the ears of the settlers, there were few in thewestern provinces who believed that there was any real danger. TheMaoris had always been peaceful and friendly with them, and they couldnot believe that those with whom they had dwelt so long could suddenlyand without any reason become bloodthirsty enemies.

Wilfrid said nothing to his parents as to what he had heard from Jack,but he talked it over with Mr. Atherton and the Allens. The latter weredisposed to make light of it, but Mr. Atherton took the matterseriously.

"There is never any saying how things will go with the natives," hesaid. "All savages seem to be alike. Up to a certain point they areintelligent and sensible; but they are like children; they are easilyexcited, superstitious in the extreme, and can be deceived without theslightest difficulty by designing people. Of course to us this story ofTe Ua's sounds absolutely absurd, but that is no reason why it shouldappear absurd to them. These people have embraced a sort ofChristianity, and they have read of miracles of all sorts, and will haveno more difficulty in believing that the angels could destroy all theEuropeans in their island than that the Assyrian army was miraculouslydestroyed before Jerusalem.

"Without taking too much account of the business, I think, Wilfrid, thatit will be just as well if all of us in these outlying settlements takea certain amount of precautions. I shall write down at once to my agentat Hawke Bay asking him to buy me a couple of dogs and send them up bythe next ship. I shall tell him that it does not matter what sort ofdogs they are so th

at they are good watch-dogs, though, of course, Ishould prefer that they should be decent dogs of their sort, dogs onecould make companions of. I should advise you to do the same.

"I shall ask Mr. Mitford to get me up at once a heavy door and shuttersfor the window strong enough to stand an assault. Here again I shouldadvise you to do the same. You can assign any reason you like to yourfather. With a couple of dogs to give the alarm, with a strong door andshutters, you need not be afraid of being taken by surprise, and it isonly a surprise that you have in the first place to fear. Of course ifthere were to be anything like a general rising we should all have togather at some central spot agreed upon, or else to quit the settlementaltogether until matters settle down. Still, I trust that nothing ofthat sort will take place. At any rate, all we have to fear and prepareagainst at present is an attack by small parties of fanatics."

Wilfrid had no difficulty in persuading his father to order a strong oakdoor and shutters for the windows, and to get a couple of dogs. He beganthe subject by saying: "Mr. Atherton is going to get some strongshutters to his window, father. I think it would be a good thing if wewere to get the same for our windows."

"What do we want shutters for, Wilfrid?"

"For just the same reason that we have been learning to use ourfirearms, father. We do not suppose that the natives, who are allfriendly with us, are going to turn treacherous. Still, as there is abare possibility of such a thing, we have taken some pains in learningto shoot straight. In the same way it would be just as well to havestrong shutters put up. We don't at all suppose we are going to beattacked, but if we are the shutters would be invaluable, and wouldeffectually prevent anything like a night surprise. The expense wouldn'tbe great, and in the unlikely event of the natives being troublesome inthis part of this island we should all sleep much more soundly andcomfortably if we knew that there was no fear of our being taken bysurprise. Mr. Atherton is sending for a couple of dogs too. I havealways thought that it would be jolly to have a dog or two here, and ifwe do not want them as guards they would be pleasant as companions whenone is going about the place."

A few days after the arrival of two large watch-dogs and of the heavyshutters and door, Mr. Mitford rode in to The Glade. He chatted for afew minutes on ordinary subjects, and then Mrs. Renshaw said: "Isanything the matter, Mr. Mitford? you look more serious than usual."

"I can hardly say that anything is exactly the matter, Mrs. Renshaw; butI had a batch of newspapers and letters from Wellington this morning,and they give rather stirring news. The Hau-Haus have come intocollision with us again. You know that a fortnight since we had newsthat they had attacked a party of our men under Captain Lloyd anddefeated them, and, contrary to all native traditions, had cut off theheads of the slain, among whom was Captain Lloyd himself. I was afraidthat after this we should soon hear more of them, and my opinion hasbeen completely justified. On the 1st of May two hundred of the Ngataiwatribe, and three hundred other natives under Te Ua's prophet Hepanaiaand Parengi-Kingi of Taranaki, attacked a strong fort on Sentry Hill,garrisoned by fifty men of the 52d Regiment under Major Short.

"The Ngataiwa took no part in the action, but the Hau-Haus charged withgreat bravery. The garrison, fortunately being warned by their yells ofwhat was coming, received them with such a heavy fire that their leadingranks were swept away, and they fell back in confusion. They made asecond charge, which was equally unsuccessful, and then fell back with aloss of fifty-two killed, among whom were both the Hau-Hau prophet andParengi-Kingi.

"The other affair has taken place in the Wellington district. Matene,another of the Hau-Hau prophets, came down to Pipiriki, a tribe of theWanganui. These people were bitterly hostile to us, as they had takenpart in some of the former fighting, and their chief and thirty-six ofhis men were killed. The tribe at once accepted the new faith. Mr.Booth, the resident magistrate, who was greatly respected among them,went up to try to smooth matters down, but was seized, and would havebeen put to death if it had not been for the interference in his favourof a young chief named Hori Patene, who managed to get him and his wifeand children safely down in a canoe to the town of Wanganui. TheHau-Haus prepared to move down the river to attack the town, and sentword to the Ngatihau branch of the tribe who lived down the river tojoin them. They and two other of the Wanganui tribes living on the lowerpart of the river refused to do so, and also refused to let them passdown the river, and sent a challenge for a regular battle to take placeon the island of Moutoa in the river.

"The challenge was accepted. At dawn on the following morning ournatives, three hundred and fifty strong, proceeded to the appointedground. A hundred picked men crossed on to the island, and the restremained on the banks as spectators. Of the hundred, fifty, divided intothree parties each under a chief, formed the advance guard, while theother fifty remained in reserve at the end of the island two hundredyards away, and too far to be of much use in the event of the advanceguard being defeated. The enemy's party were a hundred and thirtystrong, and it is difficult to understand why a larger body was not sentover to the island to oppose them, especially as the belief in theinvulnerability of the Hau-Haus was generally believed in, even by thenatives opposed to them.

"It was a curious fight, quite in the manner of the traditional warfarebetween the various tribes before our arrival on the island. The lowertribesmen fought, not for the defence of the town, for they were notvery friendly with the Europeans, having been strong supporters of theking party, but simply for the prestige of the tribe. No hostile warparty had ever forced the river, and none ever should do so. TheHau-Haus came down the river in their canoes and landed withoutopposition. Then a party of the Wanganui advance guard fired. Althoughthe Hau-Haus were but thirty yards distant none of them fell, and theirreturn volley killed the chiefs of two out of the three sections of theadvance guard and many others.

"Disheartened by the loss of their chiefs, the two sections gave way,shouting that the Hau-Haus were invulnerable. The third section, wellled by their chief, held their ground, but were driven slowly back bythe overwhelming force of the enemy. The battle appeared to be lost,when Tamehana, the sub-chief of one of the flying sections, after vainlytrying to rally his men, arrived on the ground, and, refusing to obeythe order to take cover from the Hau-Haus' fire, dashed at the enemy andkilled two of them with his double-barrelled gun. The last of the threeleaders was at this moment shot dead. Nearly all his men were more orless severely wounded, but as the Hau-Haus rushed forward they fired avolley into them at close quarters, killing several. But they still cameon, when Tamehana again rushed at them. Seizing the spear of a dead manhe drove it into the heart of a Hau-Hau. Catching up the gun andtomahawk of the fallen man, he drove the latter so deeply into the headof another foe that in wrenching it out the handle was broken. Findingthat the gun was unloaded, he dashed it in the face of his foes, andsnatching up another he was about to fire, when a bullet struck him inthe arm. Nevertheless he fired and killed his man, but the next momentwas brought to the ground by a bullet that shattered his knee.

"At this moment Hainoma, who commanded the reserve, came up with them,with the fugitives whom he had succeeded in rallying. They fired avolley, and then charged down upon the Hau-Haus with their tomahawks.After a desperate fight the enemy were driven in confusion to the upperend of the island, where they rushed into the water and attempted toswim to the right bank. The prophet was recognized among the swimmers.One of the Wanganui plunged in after him, overtook him just as hereached the opposite bank, and in spite of the prophet uttering themagic words that should have paralysed his assailant, killed him withhis tomahawk and swam back with the body to Hainoma."

"They seem to have been two serious affairs," Mr. Renshaw said; "but asthe Hau-Haus were defeated in each we may hope that we have heard thelast of them, for as both the prophets were killed the belief in theinvulnerability of Te Ua's followers must be at an end."

"I wish I could think so," Mr. Mitford said; "but it is terribly hard tokill a superstition. Te Ua will of

course say that the two prophetsdisobeyed his positive instructions and thus brought their fate uponthemselves, and the incident may therefore rather strengthen thandecrease his influence. The best part of the business in my mind is thatsome of the tribes have thrown in their lot on our side, or if notactually on our side at any rate against the Hau-Haus. After this weneed hardly fear any general action of the natives against us. There areall sorts of obscure alliances between the tribes arising frommarriages, or from their having fought on the same side in some far-backstruggle. The result is that the tribes who have these alliances withthe Wanganui will henceforth range themselves on the same side, or willat any rate hold aloof from this Pai Marire movement. This will alsoforce other tribes, who might have been willing to join in a generalmovement, to stand neutral, and I think now, that although we may have agreat deal of trouble with Te Ua's followers, we may regard any absolutedanger to the European population of the island as past.

"There may, I fear, be isolated massacres, for the Hau-Haus, with theircutting off of heads and carrying them about, have introduced anentirely new and savage feature into Maori warfare. I was inclined tothink the precautions you and Atherton are taking were rathersuperfluous, but after this I shall certainly adopt them myself.Everything is perfectly quiet here, but when we see how readily a wholetribe embrace the new religion as soon as a prophet arrives, and areready at once to massacre a man who had long dwelt among them, and forwhom they had always evinced the greatest respect and liking, it isimpossible any longer to feel confident that the natives in this part ofthe country are to be relied upon as absolutely friendly andtrustworthy.

"I am sorry now that I have been to some extent the means of inducingyou all to settle here. At the time I gave my advice things seemedsettling down at the other end of the island, and this Hau-Hau movementreached us only as a vague rumour, and seemed so absurd in itself thatone attached no importance to it."

"Pray do not blame yourself, Mr. Mitford; whatever comes of it we aredelighted with the choice we have made. We are vastly more comfortablethan we had expected to be in so short a time, and things lookpromising far beyond our expectations. As you say, you could have had noreason to suppose that this absurd movement was going to lead to suchserious consequences. Indeed you could have no ground for supposing thatit was likely to cause trouble on this side of the island, far removedas we are from the scene of the troubles. Even now these are in factconfined to the district where fighting has been going on for the lastthree or four years--Taranaki and its neighbourhood; for the WanganuiRiver, although it flows into the sea in the north of the Wellingtondistrict, rises in that of Taranaki, and the tribes who became Hau-Hausand came down the river had already taken part in the fighting with ourtroops. I really see no reason, therefore, for fearing that it willspread in this direction."

"There is no reason whatever," Mr. Mitford agreed; "only, unfortunately,the natives seldom behave as we expect them to do, and generally actprecisely as we expect they will not act. At any rate I shall set towork at once to construct a strong stockade at the back of my house. Ihave long been talking of forming a large cattle-yard there, so that itwill not in any case be labour thrown away, while if trouble should comeit will serve as a rallying-place to which all the settlers of thedistrict can drive in their horses and cattle for shelter, and wherethey can if attacked hold their own against all the natives of thedistricts."

"I really think you are looking at it in almost too serious a light, Mr.Mitford; still, the fact that there is such a rallying-place in theneighbourhood will of course add to our comfort in case we should hearalarming rumours."

"Quite so, Mr. Renshaw. My idea is there is nothing like being prepared,and though I agree with you that there is little chance of trouble inthis remote settlement, it is just as well to take precautions againstthe worst."

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

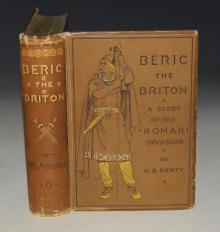

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates