- Home

- G. A. Henty

A March on London: being a story of Wat Tyler's insurrection Page 2

A March on London: being a story of Wat Tyler's insurrection Read online

Page 2

“Then, too, there are the exactions of the tax-gatherers. Some day the people will rise against them as they did in France at the time of the Jacquerie, and as they have done again and again in Flanders. At present the condition of the common people, who are but villeins and serfs, is well-nigh unbearable. Altogether the future seems to me to be dark. I confess that, being a student, the storm when it bursts will affect me but slightly, but as it is clear to me that this is not the life that you will choose it may affect you greatly; for, however little you may wish it, if civil strife comes, you, like everyone else, may be involved in it. In such an event, Edgar, act as your conscience dictates. There is always much to be said for both sides of any question, and it cannot but be so in this. I wish to lay no stress on you in any way. You cannot make a good monk out of a man who longs to be a man-at-arms, nor a warrior of a weakling who longs for the shelter of a cloister.

“Let, however, each man strive to do his best in the line he has chosen for himself. A good monk is as worthy of admiration as a good man-at-arms. I would fain have seen you a great scholar, but as it is clear that this is out of the question, seeing that your nature does not incline to study, I would that you should become a brave knight. It was with that view when I sent you to be instructed at the convent I also gave you an instructor in arms, so that, whichever way your inclinations might finally point, you should be properly fitted for it.”

At fifteen all lessons were given up, Edgar having by that time learnt as much as was considered necessary in those days. He continued his exercises with his weapons, but without any strong idea that beyond defence against personal attacks they would be of any use to him. The army was not in those days a career. When the king had need of a force to fight in France or to carry fire and sword into Scotland, the levies were called out, the nobles and barons supplied their contingent, and archers and men-at-arms were enrolled and paid by the king. The levies, however, were only liable to service for a restricted time, and beyond their personal retainers the barons in time followed the royal example of hiring men-at-arms and archers for the campaign; these being partly paid from the royal treasury, and partly from their own revenue.

At the end of the campaign, however, the army speedily dispersed, each man returning to his former avocation; save therefore for the retainers, who formed the garrisons of the castles of the nobles, there was no military career such as that which came into existence with the formation of standing armies. Nevertheless, there was honour and rank to be won in the foreign wars, and it was to these the young men of gentle blood looked to make their way. But since the death of the Black Prince matters had been quiet abroad, and unless for those who were attached to the households of powerful nobles there was, for the present, no avenue towards distinction.

Edgar had been talking these matters over with the Prior of St. Alwyth, who had taken a great fancy to him, and with whom he had, since he had given up his work at the convent, frequently had long conversations. They were engaged in one of these when this narrative begins:

“I quite agree with your father,” the Prior continued. “Were there a just and strong government, the mass of the people might bear their present position. It seems to us as natural that the serfs should be transferred with the land as if they were herds of cattle, for such is the rule throughout Europe as well as here, and one sees that there are great difficulties in the way of making any alteration in this state of things. See you, were men free to wander as they chose over the land instead of working at their vocations, the country would be full of vagrants who, for want of other means for a living, would soon become robbers. Then, too, very many would flock to the towns, and so far from bettering their condition, would find themselves worse off than before, for there would be more people than work could be found for.

[Illustration: EDGAR TALKS MATTERS OVER WITH THE PRIOR OF ST. ALWYTH.]

“So long as each was called upon only to pay his fifteenth to the king's treasury they were contented enough, but now they are called upon for a tenth as well as a fifteenth, and often this is greatly exceeded by the rapacity of the tax-collectors. Other burdens are put upon them, and altogether men are becoming desperate. Then, too, the cessation of the wars with France has brought back to the country numbers of disbanded soldiers who, having got out of the way of honest work and lost the habits of labour, are discontented and restless. All this adds to the danger. We who live in the country see these things, but the king and nobles either know nothing of them or treat them with contempt, well knowing that a few hundred men-at-arms can scatter a multitude of unarmed serfs.”

“And would you give freedom to the serfs, good Father?”

“I say not that I would give them absolute freedom, but I would grant them a charter giving them far greater rights than at present. A fifteenth of their labour is as much as they should be called upon to pay, and when the king's necessities render it needful that further money should be raised, the burden should only be laid upon the backs of those who can afford to pay it. I hear that there is much wild talk, and that the doctrines of Wickliffe have done grievous harm. I say not, my son, that there are not abuses in the Church as well as elsewhere; but these pestilent doctrines lead men to disregard all authority, and to view their natural masters as oppressors. I hear that seditious talk is uttered openly in the villages throughout the country; that there are men who would fain persuade the ignorant that all above them are drones who live on the proceeds of their labour—as if indeed every man, however high in rank, had not his share of labour and care—I fear, then, that if there should be a rising of the peasantry we may have such scenes as those that took place during the Jacquerie in France, and that many who would, were things different, be in favour of giving more extended rights to the people, will be forced to take a side against them.”

“I can hardly think that they would take up arms, Father. They must know that they could not withstand a charge of armour-clad knights and men-at- arms.”

“Unhappily, my son, the masses do not think. They believe what it pleases them to believe, and what the men who go about stirring up sedition tell them. I foresee that in the end they will suffer horribly, but before the end comes they may commit every sort of outrage. They may sack monasteries and murder the monks, for we are also looked upon as drones. They may attack and destroy the houses of the better class, and even the castles of the smaller nobles. They may even capture London and lay it in ashes, but the thought that after they had done these things a terrible vengeance would be taken, and their lot would be harder than before, would never occur to them. Take your own house for instance—what resistance could it offer to a fierce mob of peasants?”

“None,” Edgar admitted. “But why should they attack it?”

The Prior was silent.

“I know what you mean, good Father,” Edgar said, after a pause. “They say that my father is a magician, because he stirs not abroad, but spends his time on his researches. I remember when I was a small boy, and the lads of the village wished to anger me, they would shout out, 'Here is the magician's son,' and I had many a fight in consequence.”

“Just so, Edgar; the ignorant always hate that which they cannot understand; so Friar Bacon was persecuted, and accused of dabbling in magic when he was making discoveries useful to mankind. I say not that they will do any great harm when they first rise, for it cannot be said that the serfs here are so hardly treated as they were in France, where their lords had power of life and death over them, and could slay them like cattle if they chose, none interfering. Hence the hatred was so deep that in the very first outbreak the peasants fell upon the nobles and massacred them and their families.

“Here there is no such feeling. It is against the government that taxes them so heavily that their anger is directed, and I fear that this new poll-tax that has been ordered will drive them to extremities. I have news that across the river in Essex the people of some places have not only refused to pay, but have forcibly driven away the tax-gathe

rers, and when these things once begin, there is no saying how they are going to end. However, if there is trouble, I think not that at first we shall be in any danger here, but if they have success at first their pretensions will grow. They will inflame themselves. The love of plunder will take the place of their reasonable objections to over-taxation, and seeing that they have but to stretch out their hands to take what they desire, plunder and rapine will become general.”

As Edgar walked back home he felt that there was much truth in the Prior's remarks. He himself had heard many things said among the villagers which showed that their patience was well-nigh at an end. Although, since he began his studies, he had no time to keep up his former close connection with the village, he had always been on friendly terms with his old playmates, and they talked far more freely with him than they would do to anyone else of gentle blood. Once or twice he had, from a spirit of adventure, gone with them to meetings that were held after dark in a quiet spot near Dartford, and listened to the talk of strangers from Gravesend and other places. He knew himself how heavily the taxation pressed upon the people, and his sympathies were wholly with them. There had been nothing said even by the most violent of the speakers to offend him. The protests were against the exactions of the tax-gatherers, the extravagance of the court, and the hardship that men should be serfs on the land.

Once they had been addressed by a secular priest from the other side of the river, who had asserted that all men were born equal and had equal rights. This sentiment had been loudly applauded, but he himself had sense enough to see that it was contrary to fact, and that men were not born equal. One was the son of a noble, the other of a serf. One child was a cripple and a weakling from its birth, another strong and lusty. One was well-nigh a fool, and another clear-headed. It seemed to him that there were and must be differences.

Many of the secular clergy were among the foremost in stirring up the people. They themselves smarted under their disabilities. For the most part they were what were called hedge priests, men of but little or no education, looked down upon by the regular clergy, and almost wholly dependant on the contributions of their hearers. They resented the difference between themselves and the richly endowed clergy and religious houses, and denounced the priests and monks as drones who sucked the life- blood of the country.

This was the last gathering at which Edgar had been present. He had been both shocked and offended at the preaching. What was the name of the priest he knew not, nor did the villagers, but he went by the name of Jack Straw, and was, Edgar thought, a dangerous fellow. The lad had no objection to his abuse of the tax-gatherers, or to his complaints of the extravagance of the court, but this man's denunciation of the monks and clergy at once shocked and angered him. Edgar's intercourse with the villagers had removed some of the prejudices generally felt by his class, but in other respects he naturally felt as did others of his station, and he resolved to go to no more meetings.

After taking his meal with his father, Edgar mounted the horse that the latter had bought for him, and rode over to the house of one of his friends.

The number of those who had, like himself, been taught by the monk of St. Alwyth had increased somewhat, and there were, when he left, six other lads there. Three of these were intended for the Church. All were sons of neighbouring landowners, and it was to visit Albert de Courcy, the son of Sir Ralph de Courcy, that Edgar was now riding. Albert and he had been special friends. They were about the same age, but of very different dispositions. The difference between their characters was perhaps the chief attraction that had drawn them to each other. Albert was gentle in disposition, his health was not good, and he had been a weakly child. His father, who was a stout knight, regarded him with slight favour, and had acceded willingly to his desire to enter the Church, feeling that he would never make a good fighter.

Edgar, on the contrary, was tall and strongly built, and had never known a day's illness. He was somewhat grave in manner, for the companionship of his father and the character of their conversations had made him older and more thoughtful than most lads of his age. He was eager for adventure, and burned for an opportunity to distinguish himself, while his enthusiasm for noble exploits and great commanders interested his quiet friend, who had the power of admiring things that he could not hope to imitate. In him, alone of his school-fellows, did Edgar find any sympathy with his own feelings as to the condition of the people. Henry Nevil laughed to scorn Edgar's advocacy of their cause. Richard Clairvaux more than once quarrelled with him seriously, and on one or two occasions they almost betook themselves to their swords. The other three, who were of less spirit, took no part in these arguments, saying that these things did not concern them, being matters for the king and his ministers, and of no interest whatever to them.

In other respects Edgar was popular with them all. His strength and his skill in arms gave him an authority that even Richard Clairvaux acknowledged in his cooler moments. Edgar visited at the houses of all their fathers, his father encouraging him to do so, as he thought that association with his equals would be a great advantage to him. As far as manners were concerned, however, the others, with the exception of Albert de Courcy, who did not need it, gained more than he did, for Mr. Ormskirk had, during his long residence at foreign universities and his close connection with professors, acquired a certain foreign courtliness of bearing that was in strong contrast to the rough bluffness of speech and manner that characterized the English of that period, and had some share in rendering them so unpopular upon the Continent, where, although their strength and fighting power made them respected, they were regarded as island bears, and their manners were a standing jest among the frivolous nobles of the Court of France.

At the house of Sir Ralph de Courcy Edgar was a special favourite. Lady de Courcy was fond of him because her son was never tired of singing his praises, and because she saw that his friendship was really a benefit to the somewhat dreamy boy. Aline, a girl of fourteen, regarded him with admiration; she was deeply attached to her brother, and believed implicitly his assertion that Edgar would some day become a valiant knight; while Sir Ralph himself liked him both for the courtesy of his bearing and the firmness and steadiness of his character, which had, he saw, a very beneficial influence over that of Albert. Sir Ralph was now content that the latter should enter the Church, but he was unwilling that his son should become what he called a mere shaveling, and desired that he should attain power and position in his profession.

The lack of ambition and energy in his son were a grievance to him almost as great as his lack of physical powers, and he saw that although, so far there was still an absence of ambition, yet the boy had gained firmness and decision from the influence of his friend, and that he was far more likely to attain eminence in the Church than he had been before. He was himself surprised that the son of a man whose pursuits he despised should have attained such proficiency with his weapons—a matter which he had learned, when one day he had tried his skill with Edgar in a bout with swords—and he recognized that with his gifts of manner, strength and enthusiasm for deeds of arms, he was likely one day to make a name for himself.

Whenever, therefore, Edgar rode over to Sir Ralph's he was certain of a hearty welcome from all. As to the lad's opinions as to the condition of the peasantry—opinions which he would have scouted as monstrous on the part of a gentleman—Sir Ralph knew nothing, Albert having been wise enough to remain silent on the subject, the custom of the times being wholly opposed to anything like a free expression of opinion on any subject from a lad to his elders.

“It is quite a time since you were here last, Master Ormskirk,” Lady De Courcy said when he entered. “Albert so often goes up for a talk with you when he has finished his studies at the monastery that you are forgetting us here.”

“I crave your pardon, Mistress De Courcy,” Edgar said; “but, indeed, I have been working hard, for my father has obtained for me a good master for the sword—a Frenchman skilled in many devices of which my

English teachers were wholly ignorant. He has been teaching some of the young nobles in London, and my father, hearing of his skill, has had him down here, at a heavy cost, for the last month, as he was for the moment without engagements in London. It was but yesterday that he returned. Naturally, I have desired to make the utmost of the opportunity, and most of my time has been spent in the fencing-room.”

“And have you gained much by his instruction?” Sir Ralph asked.

“I hope so, Sir Ralph. I have tried my best, and he has been good enough to commend me warmly, and even told my father that I was the aptest pupil that he had.”

“I will try a bout with you presently,” the knight said. “It is nigh two years since we had one together, and my arm is growing stiff for want of practice, though every day I endeavour to keep myself in order for any opportunity or chance that may occur, by practising against an imaginary foe by hammering with a mace at a corn-sack swinging from a beam. Methinks I hit it as hard as of old, but in truth I know but little of the tricks of these Frenchmen. They availed nothing at Poictiers against our crushing downright blows. Still, I would gladly see what their tricks are like.”

CHAPTER II.

A FENCING BOUT

After he had talked for a short time with Mistress De Courcy, Edgar went to the fencing-room with Sir Ralph, and they there put on helmets and quilted leather jerkins, with chains sewn on at the shoulders.

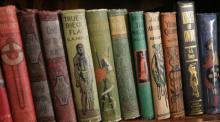

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

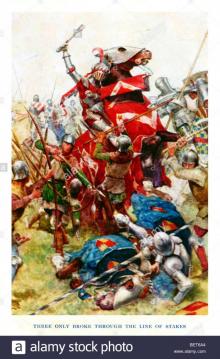

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates