- Home

- G. A. Henty

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Page 3

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Read online

Page 3

CHAPTER II

A FENCING BOUT

After he had talked for a short time with Mistress De Courcy, Edgarwent to the fencing-room with Sir Ralph, and they there put on helmetsand quilted leather jerkins, with chains sewn on at the shoulders.

"Now, you are to do your best," Sir Ralph said, as he handed a sword toEdgar, and took one himself.

So long as they played gently Edgar had all the advantage.

"You have learned your tricks well," Sir Ralph said, good-temperedly,"and, in truth, your quick returns puzzle me greatly, and I admit thatwere we both unprotected I should have no chance with you, but let ussee what you could do were we fighting in earnest," and he took down acouple of suits of complete body armour from the wall.

Albert, who was looking on, fastened the buckles for both of them.

"Ah, you know how the straps go," Sir Ralph said, in a tone ofsatisfaction. "Well, it is something to know that, even if you don'tknow what to do with it when you have got it on. Now, Master Edgar,have at you."

Edgar stood on the defence, but, strong as his arm was from constantexercise, he had some difficulty to save his head from the sweepingblows that Sir Ralph rained upon it.

"By my faith, young fellow," Sir Ralph said as, after three or fourminutes, he drew back breathless from his exertions, "your muscles seemto be made of iron, and you are fit to hold your own in a serious_melee_. You were wrong not to strike, for I know that more than oncethere was an opening had you been quick."

Edgar was well aware of the fact, but he had not taken advantage of it,for he felt that at his age it was best to abstain from trying to gaina success that could not be pleasant for the good knight.

"Well, well, we will fight no more," the latter said.

When Albert had unbuckled his father's armour and hung it up, Edgarsaid: "Now, Albert, let us have a bout."

The lad coloured hotly, and the knight burst into a hearty laugh.

"You might as soon challenge my daughter Aline. Well, put on thejerkin, Albert; it were well that you should feel what a poor creaturea man is who has never had a sword in his hand."

Albert silently obeyed his father's orders and stood up facing Edgar.They were about the same height, though Albert looked slim and delicateby the side of his friend.

"By St. George!" his father exclaimed, "you do not take up a badposture, Albert. You have looked at Edgar often enough at his exercisesto see how you ought to place yourself. I have never seen you look somanly since the day you were born. Now, strike in."

Sir Ralph's surprise at his son's attitude grew to amazement as theswords clashed together, and he saw that, although Edgar was notputting out his full strength and skill, his son, instead of beingscarce able, as he had expected, to raise the heavy sword, not onlyshowed considerable skill, but even managed to parry some of the tricksof the weapon to which he himself had fallen a victim.

"Stop, stop!" he said, at last. "Am I dreaming, or has someone elsetaken the place of my son? Take off your helmet. It is indeed Albert!"he said, as they uncovered. "What magic is this?"

"It is a little surprise that we have prepared for you, Sir Ralph,"Edgar said, "and I trust that you will not be displeased. Two years agoI persuaded Albert that there was no reason why even a priest shouldnot have a firm hand and a steady eye, and that this would help him toovercome his nervousness, and would make him strong in body as well asin arm. Since that time he has practised with me almost daily after hehad finished his studies at St. Alwyth, and my masters have done theirbest for him. Though, of course, he has not my strength, as he lacksthe practice I have had, he has gained wonderfully of late, and wouldin a few years match me in skill, for what he wants in strength hemakes up in activity."

"Master Ormskirk," the knight said, "I am beholden to you more than Ican express. His mother and I have observed during the last two yearsthat he has gained greatly in health and has widened out in theshoulders. I understand now how it has come about. We have neverquestioned him about it; indeed, I should as soon have thought ofasking him whether he had made up his mind to become king, as whetherhe had begun to use a sword. Why, I see that you have taught himalready some of the tricks that you have just learnt."

"I have not had time to instruct him in many of them, Sir Ralph, but Ishowed him one or two, and he acquired them so quickly that in anothermonth I have no doubt he will know them as well as I do."

"By St. George, you have done wonders, Edgar. As for you, Albert, I amas pleased as if I had heard that the king had made me an earl. Truly,indeed, did Master Ormskirk tell you that it would do you good to learnto use a sword. 'Tis not a priest's weapon--although many a priest andbishop have ridden to battle before now--but it has improved yourhealth and given you ten years more life than you would be likely tohave had without it. It seemed to me strange that any son of my houseshould be ignorant as to how to use a sword, and now I consider thatthat which seemed to me almost a disgrace is removed. Knows your motheraught of this?"

"No, sir. When I began I feared that my resolution would soon fade; andindeed it would have done so had not Edgar constantly encouraged me andheld me to it, though indeed at first it so fatigued me that I couldscarce walk home."

"That I can well understand, my lad. Now you shall come and tell yourmother. I have news for you, dame, that will in no small degreeastonish you," he said, as, followed by the two lads, he returned tothe room where she was sitting. "In the first place, young MasterOrmskirk has proved himself a better man than I with the sword."

"Say not so, I pray you, Sir Ralph," Edgar said. "In skill with theFrench tricks I may have had the better of you, but with a mace youwould have dashed my brains out, as I could not have guarded my headagainst the blows that you could have struck with it."

"Not just yet, perhaps," the knight said; "but when you get your fullstrength you could assuredly do so. He will be a famous knight someday, dame. But that is not the most surprising piece of news. Whatwould you say were I to tell you that this weakling of ours, althoughfar from approaching the skill and strength of his friend, is yet ableto wield a heavy sword manfully and skilfully?"

"I should say that either you were dreaming, or that I was, Sir Ralph."

"Well, I do say so in wide-awake earnest. Master Ormskirk has been hisinstructor, and for the last two years the lad has been learning of himand of his masters. That accounts for the change that we have noticedin his health and bearing. Faith, he used to go along with stoopingneck, like a girl who has outgrown her strength. Now he carries himselfwell, and his health of late has left naught to be desired. It was forthat that his friend invited him to exercise himself with the sword;and indeed his recipe has done wonders. His voice has gained strength,and though it still has a girlish ring about it, he speaks more firmlyand assuredly than he used to do."

"That is indeed wonderful news, Sir Ralph, and I rejoice to hear it.Master Ormskirk, we are indeed beholden to you. For at one time Idoubted whether Albert would ever live to grow into a man; and of lateI have been gladdened at seeing so great a change in him, though Idreamed not of the cause."

Aline had stood open-mouthed while her father was speaking, and nowstole up to Albert's side.

"I am pleased, brother," she said. "May I tell them now what happenedthe other day with the black bull, you charged me to say nothing about?"

"What is this about the black bull, Aline?" her father said, as hecaught the words.

"It was naught, sir," Albert replied, colouring, "save that the blackbull in the lower meadow ran at us, and I frightened him away."

"No, no, father," the girl broke in, "it was not that at all. We werewalking through the meadow together when the black bull ran at us.Albert said to me, 'Run, run, Aline!' and I did run as hard as I could;but I looked back for some time as I ran, being greatly terrified as towhat would come to Albert. He stood still. The bull lowered his headand rushed at him. Then he sprang aside just as I expected to see himtossed into the air, caught hold of the bull's tail as it went past him

and held on till the bull was close to the fence, and then he let goand scrambled over, while the bull went bellowing down the field."

"Well done, well done!" Sir Ralph said. "Why, Albert, it seemsmarvellous that you should be doing such things; that black bull is aformidable beast, and the strongest man, if unarmed, might well feeldiscomposed if he saw him coming rushing at him. I will wager that ifyou had not had that practice with the sword, you would not have hadthe quickness of thought that enabled you to get out of the scrape. Youmight have stood between the bull and your sister, but if you had doneso you would only have been tossed, and perhaps gored or trampled todeath afterwards. I will have the beast killed, or otherwise he will bedoing mischief. There are not many who pass through the field, still Idon't want to have any of my tenants killed.

"Well, Master Ormskirk, both my wife and I feel grateful to you forwhat you have done for Albert. There are the makings of a man in himnow, let him take up what trade he will. I don't say much, boy, it isnot my way; but if you ever want a friend, whether it be at court orcamp, you can rely upon me to do as much for you as I would for one ofmy own; maybe more, for I deem that a man cannot well ask for favoursfor those of his own blood, but he can speak a good word, and even urgehis suit for one who is no kin to him. So far as I understand, you havenot made up your mind in what path you will embark."

"No, Sir Ralph, for at present, although we can scarce be said to be atpeace with the French, we are not fighting with them. Had it been so Iwould willingly have joined the train of some brave knight raising aforce for service there. There is ever fighting in the North, but withthe Scots it is but a war of skirmishes, and not as it was in Edward'sreign. Moreover, by what my father says, there seems no reason forharrying Scotland far and near, and the fighting at present is scarceof a nature in which much credit is to be gained."

"You might enter the household of some powerful noble, lad."

"My father spoke to me of that, Sir Ralph, but told me that he wouldrather that I were with some simple knight than with a great noble, forthat in the rivalries between these there might be troubles come uponthe land, and maybe even civil strife; that one who might hold his headhighest of all one day might on the morrow have it struck off with theexecutioner's axe, and that at any rate it were best at present to livequietly and see how matters went before taking any step that would bindme to the fortunes of one man more than another."

"Your father speaks wisely. 'Tis not often that men who live in books,and spend their time in pouring over mouldy parchments, and inwell-nigh suffocating themselves with stinking fumes have common sensein worldly matters. But when I have conversed with your father, I havealways found that, although he takes not much interest in publicaffairs at present, he is marvellously well versed in our history, andcan give illustrations in support of what he says. Well, whenever thetime comes that he thinks it good for you to leave his fireside andventure out into the world, you have but to come to me, and I will, sofar as is in my power, further your designs."

"I thank you most heartily, Sir Ralph, and glad am I to have been ofservice to Albert, who has been almost as a brother to me since wefirst met at St. Alwyth."

"I would go over and see your father, and have a talk with him aboutyou, but I ride to London to-morrow, and may be forced to tarry therefor some time. When I return I will wait upon him and have a talk as tohis plans for you. Now, I doubt not, you would all rather be wanderingabout the garden than sitting here with us, so we will detain you nolonger."

"Albert, I am very angry with you and Master Ormskirk that you did nottake me into your counsel and tell me about your learning to use thesword," Aline said, later on, as they watched Edgar ride away throughthe gateway of the castle. "I call it very unkind of you both."

"We had not thought of being unkind, Aline," Albert said, quietly."When we began I did not feel sure that either my strength or myresolution would suffice to carry me through, and indeed it was atfirst very painful work for me, having never before taken any strongexercise, and often I would have given it up from the pain and fatiguethat it caused me, had not Edgar urged me to persevere, saying that intime I should feel neither pain nor weariness. Therefore, at first Isaid nothing to you, knowing that it would disappoint you did I give itup, and then when my arm gained strength, and Edgar encouraged me bypraising my progress, and I began to hope that I might yet come to bestrong and gain skill with the weapon, I kept it back in order that Imight, as I have done to-day, have the pleasure of surprising you, aswell as my father, by showing that I was not so great a milksop as youhad rightly deemed me."

"I never thought that you were a milksop, Albert," his sister said,indignantly. "I knew that you were not strong, and was sorry for it,but it was much nicer for me that you should be content to walk andride with me, and to take interest in things that I like, instead ofbeing like Henry Nevil or Richard Clairvaux, who are always talking andthinking of nothing but how they would go to the wars, and what theywould do there."

"There was no need that I should do that, Aline. Edgar is a much betterswordsman than either of them, and knows much more, and is much morelikely to be a famous knight some day than either Nevil or Clairvaux,but I am certain that you do not hear him talk about it."

"No, Edgar is nice, too," the girl said, frankly, "and very strong. Doyou not remember how he carried me home more than two miles, when ayear ago I fell down when I was out with you, and sprained my ankle.And now, Albert, perhaps some day you will get so strong that you maynot think of going into the Church and shutting yourself up all yourlife in a cloister, but may come to be famous too."

"I have not thought of that, Aline," he said, gravely. "If ever I didchange my mind, it would be that I might always be with Edgar and begreat friends with him, all through our lives, just as we are now."

Sir Ralph and his wife were at the time discussing the same topic. "Itmay yet be, Agatha, that, after all, the boy may give up this thoughtof being a churchman. I have never said a word against it hitherto,because it seemed to me that he was fit for nothing else, but now thatone sees that he has spirit, and has, thanks to his friend, acquired ataste for arms, and has a strength I never dreamt he possessed, thematter is changed. I say not yet that he is like to become a famousknight, but it needs not that every one should be able to swing a heavymace and hold his own in a _melee_. There are many posts at court whereone who is discreet and long-headed may hold his own, and gain honour,so that he be not a mere feeble weakling who can be roughly pushed tothe wall by every blusterer."

"I would ask him no question concerning it, Sir Ralph," his wife said."It may be as you say, but methinks that it will be more likely that hewill turn to it if you ask him no questions, but leave him to think itout for himself. The lad Edgar has great influence over him, and willassuredly use it for good. As for myself, it would be no such greatgrief were Albert to enter the Church as it would be to you, though I,too, would prefer that he should not be lost to us, and would ratherthat he went to Court and played his part there. I believe that he hastalent. The prior of St. Alwyth said that he and young Ormskirk were byfar his most promising pupils; of course, the latter has now ceased tostudy with him, having learned as much as is necessary for a gentlemanto know if he be not intended for the Church. Albert is well aware whatyour wishes are, and that if you have said naught against his taking upthat profession, it was but because you deemed him fit for no other.Now, you will see that, having done so much, he may well do more, andit may be that in time he may himself speak to you and tell you that hehas changed his mind on the matter."

"Perhaps it would be best so, dame, and I have good hope that it willbe as you say. I care not much for the Court, where Lancaster andGloucester overshadow the king. Still, a man can play his part there;though I would not that he should attach himself to Lancaster's factionor to Gloucester's, for both are ambitious, and it will be a strugglebetween them for supremacy. If he goes he shall go as a king's man.Richard, as he grows up, will resent the tutelage in which he is he

ld,but will not be able to shake it off, and he will need men he can relyupon--prudent and good advisers, the nearer to his own age the better,and it may well be that Albert would be like to gain rank and honourmore quickly in this way than by doughty deeds in the field. It is goodthat each man should stick to his last. As for me, I would rather delveas a peasant than mix in the intrigues of a Court. But there must becourtiers as well as fighters, and I say not aught against them.

"The boy with his quiet voice, and his habit of going about makinglittle more noise than a cat, is far better suited for such a life thanI with my rough speech and fiery temper. For his manner he has alsomuch to thank young Ormskirk. Edgar caught it from his father, who,though a strange man according to my thinking, is yet a singularlycourteous gentleman, and Albert has taken it from his friend. Well,wife, I shall put this down as one of my fortunate days, for never haveI heard better news than that which Albert gave me this afternoon."

When Edgar returned home he told his father what had taken place.

"I thought that Sir Ralph would be mightily pleased some day when heheard that his son had been so zealously working here with you, and Itoo was glad to see it. I am altogether without influence to push yourfortunes. Learning I can give you, but I scarce know a man at Court,for while I lived at Highgate I seldom went abroad, and save for avisit now and then from some scholar anxious to consult me, scarce abeing entered my house. Therefore, beyond relating to you such mattersof history as it were well for you to know, and by telling you of thedeeds of Caesar and other great commanders, I could do naught for you."

"You have done a great deal for me, father. You have taught me more ofmilitary matters, and of the history of this country, and of France andItaly, than can be known to most people, and will assuredly be of muchadvantage to me in the future."

"That may be so, Edgar, but the great thing is to make the first start,and here I could in no way aid you. I have often wondered how thismatter could be brought about, and now you have obtained a powerfulfriend; for although Sir Ralph De Courcy is but a simple knight, withno great heritage, his wife is a daughter of Lord Talbot, and hehimself is one of the most valiant of the nobles and knights who foughtso stoutly in France and Spain, and as such is known to, and respectedby, all those who bore a part in those wars. He therefore can do foryou the service that of all others is the most necessary.

"The king himself is well aware that he was one of the knights in whomthe Black Prince, his father, had the fullest confidence, and to whomhe owed his life more than once in the thick of a _melee_. Thus, then,when the time comes, he will be able to secure for you a post in thefollowing of some brave leader. I would rather that it were so than inthe household of any great noble, who would assuredly take one side orother in the factions of the Court. You are too young for this as yet,being too old to be a page, too young for an esquire, and musttherefore wait until you are old enough to enter service either as anesquire or as one of the retinue of a military leader."

"I would rather be an esquire and ride to battle to win my spurs. Ishould not care to become a knight simply because I was the owner of somany acres of land, but should wish to be knighted for service in thefield."

"So would I also, Edgar. My holding here is large enough to entitle meto the rank of knight did I choose to take it up, but indeed it wouldbe with me as it is with many others, an empty title. Holding landenough for a knight's fee, I should of course be bound to send so manymen into the field were I called upon to do so, and should send you asmy substitute if the call should not come until you are two or threeyears older; but in this way you would be less likely to gainopportunities for winning honour than if you formed part of thefollowing of some well-known knight. Were a call to come you could gowith few better than Sir Ralph, who would be sure to be in the thick ofit. But if it comes not ere long, he may think himself too old to takethe field, and his contingent would doubtless be led by some knight ashis substitute."

"I think not, father, that Sir Ralph is likely to regard himself aslying on the shelf for some time to come; he is still a very strongman, and he would chafe like a caged eagle were there blows to bestruck in France, and he unable to share in them."

Four days later a man who had been down to the town returned with abudget of news. Edgar happened to be at the door when he rode past.

"What is the news, Master Clement?" he said, for he saw that the manlooked excited and alarmed.

"There be bad news, young master, mighty bad news. Thou knowest how inEssex men have refused to pay the poll-tax, but there has been naughtof that on this side of the river as yet, though there is soregrumbling, seeing that the tax-collectors are not content with drawingthe tax from those of proper age, but often demand payments for boysand girls, who, as they might see, are still under fourteen. Ithappened so to-day at Dartford. One of the tax-collectors went to thehouse of Wat the Tyler. His wife had the money for his tax and hers,but the man insolently demanded tax for the daughter, who is but a girlof twelve; and when her mother protested that the child was two yearsshort of the age, he offered so gross an insult to the girl that sheand her mother screamed out. A neighbour ran with the news to Wat, whowas at his work on the roof of a house near, and he, being full ofwrath thereat, ran hastily home, and entering smote the man so heavilyon the head with a hammer he carried, that he killed him on the spot.

"The collectors' knaves would have seized Wat, but the neighbours ranin and drove them from the town with blows. The whole place is in aferment. Many have arms in their hands, and are declaring that theywill submit no more to the exactions, and will fight rather than pay,for that their lives are of little value to them if they are to beground to the earth by these leeches. The Fleming traders in the townhave hidden away, for in their present humour the mob might well fallupon them and kill them."

It was against the Flemings indeed that the feelings of the countrypeople ran highest. This tax was not, as usual, collected by the royalofficers, but by men hired by the Flemish traders settled in England.The proceeds of it had been bestowed upon several young nobles,intimates of the king. These had borrowed money from the Flemings onthe security of the tax; the amount that it was likely to produce hadbeen considerably overrated, and the result was that the Flemings,finding that they would be heavy losers by the transaction, orderedtheir collectors to gather in as much as possible. These obeyed theinstructions, rendering by their conduct the exaction of the poll-taxeven more unpopular than it would have been had it been collected bythe royal officers, who would have been content with the sum that couldbe legally demanded.

"This is serious news," Edgar said, gravely, "and I fear that muchtrouble may come of it. Doubtless the tax-collector misbehaved himselfgrossly, but his employers will take no heed of that, and will laycomplaints before the king of the slaying of one of their servants andof the assault upon others by a mob of Dartford, so that erelong weshall be having a troop of men-at-arms sent hither to punish the town."

"Ay, young master, but not being of Dartford I should not care so muchfor that; but there are hot spirits elsewhere, and there are many whowould be like to take up arms as well as the men at Dartford, and toresist all attacks; then the trouble would spread, and there is nosaying how far it may grow."

"True enough, Clement; well, we may hope that when men's minds becomecalmer the people of Dartford will think it best to offer to pay a finein order to escape bloodshed."

"It may be so," the man said, shaking his head, "though I doubt it.There has been too much preaching of sedition. I say not that thepeople have not many and real grievances, but the way to right them isnot by the taking up of arms, but by petition to the crown andparliament."

He rode on, and Edgar, going in to his father, told him what he hadheard from Clement.

"'Tis what I feared," Mr. Ormskirk said. "The English are a patientrace, and not given, as are those of foreign nations, to sudden burstsof rage. So long as the taxation was legal they would pay, howeverhardly it pressed them, but when it comes t

o demanding money forchildren under the age, and to insulting them, it is pushing matterstoo far, and I fear with you, Edgar, that the trouble will spread. I amsorry for these people, for however loudly they may talk and howevervaliant they may be, they can assuredly offer but a weak resistance toa strong body of men-at-arms, and they will but make their case worseby taking up arms.

"History shows that mobs are seldom able to maintain a struggle againstauthority. Just at first success may attend them, but as soon as thosewho govern recover from their first surprise they are not long beforethey put down the movement. I am sorry, not only for the menthemselves, but for others who, like myself, altogether disapprove ofany rising. Just at first the mob may obey its leaders and act withmoderation; but they are like wild beasts--the sight of blood maddensthem--and if this rising should become a serious one, you will see thatthere will be burnings and ravagings. Heads will be smitten off, andafter slaying those they consider the chief culprits, they will turnagainst all in a better condition than themselves.

"The last time Sir Ralph De Courcy was over here he told me that thepriest they called Jack Straw and many others were, he heard, not onlypreaching sedition against the government, but the seizure of the goodsof the wealthy, the confiscation of the estates of the monasteries, andthe division of the wealth of the rich. A nice programme, and just theone that would be acceptable to men without a penny in their pockets.Sir Ralph said that he would give much if he, with half a dozenmen-at-arms, could light upon a meeting of these people, when he wouldgive them a lesson that would silence their saucy tongues for a longtime to come. I told him I was glad that he had not the opportunity,for that methought it would do more harm than good. 'You won't thinkso,' he said, 'when there is a mob of these rascals thundering at yourdoor, and resolved to make a bonfire of your precious manuscripts andto throw you into the midst of it.' 'I have no doubt,' I replied, 'thatat such a time I should welcome the news of the arrival of you and themen-at-arms, but I have no store of goods that would attract theircupidity.' 'No,' the knight said, 'but you know that among the commonpeople you are accounted a magician, because you are wiser than theyare.'

"'I know that,' I replied; 'it is the same in all countries. Thecredulous mob think that a scholar, although he may spend his life intrying to make a discovery that will be of inestimable value to them,is a magician and in league with the devil. However, although not afighting man, I may possess means of defence that are to the full asserviceable as swords and battle-axes. I have long foreseen that shouldtrouble arise, the villagers of St. Alwyth would be like enough toraise the cry of magician, and to take that opportunity of riddingthemselves of one they vaguely fear, and many months ago I made somepreparations to meet such a storm and to show them that a magician isnot altogether defenceless, and that the compounds in his power arewell-nigh as dangerous as they believe, only not in the same way.'

"'Well, I hope that you will find it so if there is any trouble; but Irecommend you, if you hear that there is any talk in the village ofmaking an assault upon you that you send a messenger to me straightway,and you may be sure that ere an hour has passed I will be here withhalf a dozen stout fellows who will drive this rabble before them likesheep.'

"'I thank you much for the offer, Sir Ralph, and will bear it in mindshould there be an occasion, but I think that I may be able to managewithout need for bloodshed. You are a vastly more formidable enemy thanI am, but I imagine that they have a greater respect for my supposedmagical powers than they have for the weight of your arm, heavy thoughit be.'

"'Perhaps it is so, my friend,' Sir Ralph said, grimly, 'for they havenot felt its full weight yet, though I own that I myself would rathermeet the bravest knight in battle than raise my hand against a man whomI believed to be possessed of magical powers.'

"I laughed, and said that so far as I knew no such powers existed.'Your magicians are but chemists,' I said. 'Their object of search isthe Elixir of Life or the Philosopher's Stone; they may be powerful forgood, but they are assuredly powerless for evil.'

"'But surely you believe in the power of sorcery?' he said. 'All menknow that there are sorcerers who can command the powers of the air andbring terrible misfortunes down on those that oppose them.'

"'I do not believe that there are men who possess such powers,' I said.'There are knaves who may pretend to have such powers, but it is onlyto gain money from the credulous. In all my reading I have never comeupon a single instance of any man who has really exercised such powers,nor do I believe that such powers exist. Men have at all times believedin portents, and even a Roman army would turn back were it on the marchagainst an enemy, if a hare ran across the road they were following; Isay not that there may not be something in such portents, though evenof this I have doubts. Still, like dreams, they may be sent to warn us,but assuredly man has naught to do with their occurrence, and I would,were I not a peaceful man, draw my sword as readily against the mostfamous enchanter as against any other man of the same strength andskill, with his weapon.'

"I could see that the good knight was shocked at the light way in whichI spoke of magicians; and, indeed, the power of superstition over men,otherwise sensible, is wonderful. However, he took his leave withoutsaying more than that he and the men-at-arms would be ready if I sentfor them."

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

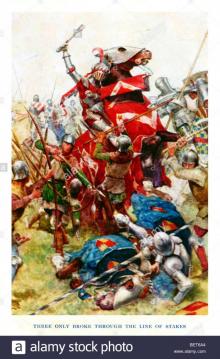

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates