- Home

- G. A. Henty

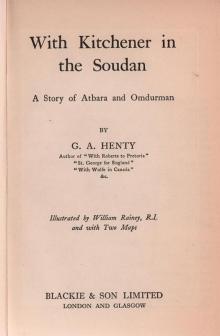

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Page 4

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Read online

Page 4

Chapter 3: A Terrible Disaster.

It was an anxious time for his wife, after Gregory started. He, andthose with him, had left with a feeling of confidence that theinsurrection would speedily be put down. The garrison of Khartoum hadinflicted several severe defeats upon the Mahdi, but had also sufferedsome reverses. This, however, was only to be expected, when the troopsunder him were scarcely more disciplined than those of the Dervishes,who had always been greatly superior in numbers, and inspired with afanatical belief in their prophet. But with British officers tocommand, and British officers to drill and discipline the troops, therecould be no fear of a recurrence of these disasters.

Before they started, Mrs. Hilliard had become intimate with the wife ofHicks Pasha, and those of the other married officers, and had paidvisits with them to the harems of high Turkish officials. Visits werefrequently exchanged, and what with these, and the care of the boy, hertime was constantly occupied. She received letters from Gregory, asfrequently as possible, after his arrival at Omdurman, and until he setout with the main body, under the general, on the way to El Obeid.

Before starting, he said he hoped that, in another two months, thecampaign would be over, El Obeid recovered, and the Mahdi smashed up;and that, as soon as they returned to Khartoum, Hicks Pasha would sendfor his wife and daughters, and the other married officers for theirwives; and, of course, she would accompany them.

"I cannot say much for Omdurman," he wrote; "but Khartoum is a niceplace. Many of the houses there have shady gardens. Hicks has promisedto recommend me for a majority, in one of the Turkish regiments. In theintervals of my own work, I have got up drill. I shall, of course, tellhim then what my real name is, so that I can be gazetted in it. It islikely enough that, even after we defeat the Mahdi, this war may go onfor some time before it is stamped out; and in another year I may be afull-blown colonel, if only an Egyptian one; and as the pay of theEnglish officers is good, I shall be able to have a very comfortablehome for you.

"I need not repeat my instructions, darling, as to what you must do inthe event, improbable as it is, of disaster. When absolutely assured ofmy death, but not until then, you will go back to England with the boy,and see my father. He is not a man to change his mind, unless I were tohumble myself before him; but I think he would do the right thing foryou. If he will not, there is the letter for Geoffrey. He has nosettled income at present, but when he comes into the title he will, Ifeel quite certain, make you an allowance. I know that you would, foryourself, shrink from doing this; but, for the boy's sake, you will nothesitate to carry out my instructions. I should say you had betterwrite to my father, for the interview might be an unpleasant one; butif you have to appeal to Geoffrey, you had better call upon him andshow him this letter. I feel sure that he will do what he can.

"Gregory."

A month later, a messenger came up from Suakim with a despatch, datedOctober 3rd. The force was then within a few days' march of El Obeid.The news was not altogether cheering. Hordes of the enemy hovered abouttheir rear. Communication was already difficult, and they had to dependupon the stores they carried, and cut themselves off altogether fromthe base. He brought some private letters from the officers, and amongthem one for Mrs. Hilliard. It was short, and written in pencil:

"In a few days, Dear, the decisive battle will take place; and althoughit will be a tough fight, none of us have any fear of the result. Inthe very improbable event of a defeat, I shall, if I have time, slip onthe Arab dress I have with me, and may hope to escape. However, I havelittle fear that it will come to that. God bless and protect you, andthe boy!

"Gregory."

A month passed away. No news came from Hicks Pasha, or any of hisofficers. Then there were rumours current in the bazaars, of disaster;and one morning, when Annie called upon Lady Hicks, she found severalof the ladies there with pale and anxious faces. She paused at thedoor.

"Do not be alarmed, Mrs. Hilliard," Lady Hicks said. "Nizim Pasha hasbeen here this morning. He thought that I might have heard the rumoursthat are current in the bazaar, that there has been a disaster, but hesays there is no confirmation whatever of these reports. He does notdeny, however, that they have caused anxiety among the authorities; forsometimes these rumours, whose origin no one knows, do turn out to becorrect. He said that enquiries have been made, but no foundation forthe stories can be got at. I questioned him closely, and he says thathe can only account for them on the ground that, if a victory had beenwon, an official account from government should have been here beforethis; and that it is solely on this account that these rumours have gotabout. He said there was no reason for supposing that this silencemeant disaster. A complete victory might have been won; and yet themessenger with the despatches might have been captured, and killed, bythe parties of tribesmen hanging behind the army, or wandering aboutthe country between the army and Khartoum. Still, of course, this ismaking us all very anxious."

The party soon broke up, none having any reassuring suggestions tooffer; and Annie returned to her lodging, to weep over her boy, andpray for the safety of his father. Days and weeks passed, and still noword came to Cairo. At Khartoum there was a ferment among the nativepopulation. No secret was made of the fact that the tribesmen who cameand went all declared that Hicks Pasha's army was utterly destroyed. Atlength, the Egyptian government announced to the wives of the officersthat pensions would be given to them, according to the rank of theirhusbands. As captain and interpreter, Gregory's wife had but a smallone, but it was sufficient for her to live upon.

One by one, the other ladies gave up hope and returned to England, butAnnie stayed on. Misfortune might have befallen the army, but Gregorymight have escaped in disguise. She had, like the other ladies, put onmourning for him; for had she declared her belief that he might stillbe alive, she could not have applied for the pension, and this wasnecessary for the child's sake. Of one thing she was determined. Shewould not go with him, as beggars, to the father who had cast Gregoryoff; until, as he had said, she received absolute news of his death.She was not in want; but as her pension was a small one, and she feltthat it would be well for her to be employed, she asked Lady Hicks,before she left, to mention at the houses of the Egyptian ladies towhom she went to say goodbye, that Mrs. Hilliard would be glad to givelessons in English, French, or music.

The idea pleased them, and she obtained several pupils. Some of thesewere the ladies themselves, and the lessons generally consisted insitting for an hour with them, two or three times a week, and talkingto them; the conversation being in short sentences, of which she gavethem the English translation, which they repeated over and over again,until they knew them by heart. This caused great amusement, and wasaccompanied by much laughter, on the part of the ladies and theirattendants.

Several of her pupils, however, were young boys and girls, and theteaching here was of a more serious kind. The lessons to the boys weregiven the first thing in the morning, and the pupils were brought toher house by attendants. At eleven o'clock she taught the girls, andreturned at one, and had two hours more teaching in the afternoon. Shecould have obtained more pupils, had she wished to; but the pay shereceived, added to her income, enabled her to live very comfortably,and to save up money. She had a Negro servant, who was very fond of theboy, and she could leave him in her charge with perfect confidence,while she was teaching.

In the latter part of 1884, she ventured to hope that some news mightyet come to her, for a British expedition had started for the relief ofGeneral Gordon, who had gone up early in the year to Khartoum; where itwas hoped that the influence he had gained among the natives, at thetime he was in command of the Egyptian forces in the Soudan, wouldenable him to make head against the insurrection. His arrival had beenhailed by the population, but it was soon evident to him that, unlessaided by England with something more than words, Khartoum must finallyfall.

But his requests for aid were slighted. He had asked that two regimentsshould be sent from Suakim, to keep open the route to Berber, but Mr.Gladsto

ne's government refused even this slight assistance to the manthey had sent out, and it was not until May that public indignation, atthis base desertion of one of the noblest spirits that Britain everproduced, caused preparations for his rescue to be made; and it wasDecember before the leading regiment arrived at Korti, far up the Nile.

After fighting two hard battles, a force that had marched across theloop of the Nile came down upon it above Metemmeh. A party started upthe river at once, in two steamers which Gordon had sent down to meetthem, but only arrived near the town to hear that they were too late,that Khartoum had fallen, and that Gordon had been murdered. The armywas at once hurried back to the coast, leaving it to the Mahdists--moretriumphant than ever--to occupy Dongola; and to push down, andpossibly, as they were confident they should do, to capture Egyptitself.

The news of the failure was a terrible blow to Mrs. Hilliard. She hadhoped that, when Khartoum was relieved, some information at least mightbe obtained, from prisoners, as to the fate of the British officers atEl Obeid. That most of them had been killed was certain, but she stillclung to the hope that her husband might have escaped from the generalmassacre, thanks to his knowledge of the language, and the disguise hehad with him; and even that if captured later on he might be aprisoner; or that he might have escaped detection altogether, and bestill living among friendly tribesmen. It was a heavy blow to her,therefore, when she heard that the troops were being hurried down tothe coast, and that the Mahdi would be uncontested master of Egypt, asfar as Assouan.

She did, however, receive news when the force returned to Cairo, which,although depressing, did not extinguish all hope. Lieutenant ColonelColborne, by good luck, had ascertained that a native boy in theservice of General Buller claimed to have been at El Obeid. Uponquestioning him closely, he found out that he had unquestionably beenthere, for he described accurately the position Colonel Colborne--whohad started with Hicks Pasha, but had been forced by illness toreturn--had occupied in one of the engagements. The boy was then theslave of an Egyptian officer of the expedition.

The army had suffered much from want of water, but they had obtainedplenty from a lake within three days' march from El Obeid. From thispoint they were incessantly fired at, by the enemy. On the second daythey were attacked, but beat off the enemy, though with heavy loss tothemselves. The next day they pressed forward, as it was necessary toget to water; but they were misled by their guide, and at noon theArabs burst down upon them, the square in which the force was marchingwas broken, and a terrible slaughter took place. Then Hicks Pasha, withhis officers, seeing that all was lost, gathered together and kept theenemy at bay with their revolvers, till their ammunition was exhausted.After that they fought with their swords till all were killed, HicksPasha being the last to fall. The lad himself hid among the dead andwas not discovered until the next morning, when he was made a slave bythe man who found him.

This was terrible! But there was still hope. If this boy had concealedhimself among the dead, her husband might have done the same. Not beinga combatant officer, he might not have been near the others when theaffair took place; and moreover, the lad had said that the blackregiment in the rear of the square had kept together and marched away;he believed all had been afterwards killed, but this he did not know.If Gregory had been there when the square was broken, he might wellhave kept with them, and at nightfall slipped on his disguise and madehis escape. It was at least possible--she would not give up all hope.

So years went on. Things were quiet in Egypt. A native army had beenraised there, under the command of British officers, and these hadchecked the northern progress of the Mahdists and restored confidencein Egypt. Gregory--for the boy had been named after his father--grew upstrong and hearty. His mother devoted her evenings to his education.From the Negress, who was his nurse and the general servant of thehouse, he had learnt to talk her native language. She had been carriedoff, when ten years old, by a slave-raiding party, and sold to anEgyptian trader at Khartoum; been given by him to an Atbara chief, withwhom he had dealings; and, five years later, had been captured in atribal war by the Jaalin. Two or three times she had changed masters,and finally had been purchased by an Egyptian officer, and brought downby him to Cairo. At his death, four years afterwards, she had beengiven her freedom, being now past fifty, and had taken service withGregory Hilliard and his wife. Her vocabulary was a large one, and shewas acquainted with most of the dialects of the Soudan tribes.

From the time when her husband was first missing, Mrs. Hilliardcherished the idea that, some day, the child might grow up and searchfor his father; and, perhaps, ascertain his fate beyond all doubt. Shewas a very conscientious woman, and was resolved that, at whatever painto herself, she would, when once certain of her husband's death, go toEngland and obtain recognition of his boy by his family. But it waspleasant to think that the day was far distant when she could give uphope. She saw, too, that if the Soudan was ever reconquered, theknowledge of the tribal languages must be of immense benefit to herson; and she therefore insisted, from the first, that the woman shouldalways talk to him in one or other of the languages that she knew.

Thus Gregory, almost unconsciously, acquired several of the dialectsused in the Soudan. Arabic formed the basis of them all, except theNegro tongue. At first he mixed them up, but as he grew, Mrs. Hilliardinsisted that his nurse should speak one for a month, and then useanother; so that, by the time he was twelve years old, the boy couldspeak in the Negro tongue, and half a dozen dialects, with equalfacility.

His mother had, years before, engaged a teacher of Arabic for him. Thishe learned readily, as it was the root of the Egyptian and the otherlanguages he had picked up. Of a morning, he sat in the school andlearned pure Arabic and Turkish, while the boys learned English; andtherefore, without an effort, when he was twelve years old he talkedthese languages as well as English; and had, moreover, a smattering ofItalian and French, picked up from boys of his own age, for his motherhad now many acquaintances among the European community.

While she was occupied in the afternoon, with her pupils, the boy hadliberty to go about as he pleased; and indeed she encouraged him totake long walks, to swim, and to join in all games and exercises.

"English boys at home," she said, "have many games, and it is owing tothese that they grow up so strong and active. They have moreopportunities than you, but you must make the most of those that youhave. We may go back to England some day, and I should not at all likeyou to be less strong than others."

As, however, such opportunities were very small, she had an apparatusof poles, horizontal bars, and ropes set up, such as those she hadseen, in England, in use by the boys of one of the families where shehad taught, before her marriage; and insisted upon Gregory's exercisinghimself upon it for an hour every morning, soon after sunrise. As shehad heard her husband once say that fencing was a splendid exercise,not only for developing the figure, but for giving a good carriage aswell as activity and alertness, she arranged with a Frenchman who hadserved in the army, and had gained a prize as a swordsman in theregiment, to give the boy lessons two mornings in the week.

Thus, at fifteen, Gregory was well grown and athletic, and had much ofthe bearing and appearance of an English public-school boy. His motherhad been very particular in seeing that his manners were those of anEnglishman.

"I hope the time will come when you will associate with Englishgentlemen, and I should wish you, in all respects, to be like them. Youbelong to a good family; and should you, by any chance, some day gohome, you must do credit to your dear father."

The boy had, for some years, been acquainted with the family story,except that he did not know the name he bore was his father's Christianname, and not that of his family.

"My grandfather must have been a very bad man, Mother, to havequarreled with my father for marrying you."

"Well, my boy, you hardly understand the extent of the exclusiveness ofsome Englishmen. Of course, it is not always so, but to some people,the idea of their sons or daughters marrying

into a family of less rankthan themselves appears to be an almost terrible thing. As I have toldyou, although the daughter of a clergyman, I was, when I became anorphan, obliged to go out as a governess."

"But there was no harm in that, Mother?"

"No harm, dear; but a certain loss of position. Had my father beenalive, and had I been living with him in a country rectory, yourgrandfather might not have been pleased at your father's falling inlove with me, because he would probably have considered that, being, asyou know by his photograph, a fine, tall, handsome man, and having thebest education money could give him, he might have married very muchbetter; that is to say, the heiress of a property, or into a family ofinfluence, through which he might have been pushed on; but he would nothave thought of opposing the marriage on the ground of my family. But agoverness is a different thing. She is, in many cases, a lady in everyrespect, but her position is a doubtful one.

"In some families she is treated as one of themselves. In others, herposition is very little different from that of an upper servant. Yourgrandfather was a passionate man, and a very proud man. Your father'selder brother was well provided for, but there were two sisters, andthese and your father he hoped would make good marriages. He lived invery good style, but your uncle was extravagant, and your grandfatherwas over indulgent, and crippled himself a good deal in paying thedebts that he incurred. It was natural, therefore, that he should haveobjected to your father's engagement to what he called a pennilessgoverness. It was only what was to be expected. If he had stated hisobjections to the marriage calmly, there need have been no quarrel.Your father would assuredly have married me, in any case; and yourgrandfather might have refused to assist him, if he did so, but thereneed have been no breakup in the family, such as took place.

"However, as it was, your father resented his tone, and what had beenmerely a difference of opinion became a serious quarrel, and they neversaw each other, afterwards. It was a great grief to me, and it wasowing to that, and his being unable to earn his living in England, thatyour father brought me out here. I believe he would have done well athome, though it would have been a hard struggle. At that time I wasvery delicate, and was ordered by the doctors to go to a warm climate,and therefore your father accepted a position of a kind which, atleast, enabled us to live, and obtained for me the benefit of a warmclimate.

"Then the chance came of his going up to the Soudan, and there was acertainty that, if the expedition succeeded, as everyone believed itwould, he would have obtained permanent rank in the Egyptian army, andso recovered the position in life that he had voluntarily given up, formy sake."

"And what was the illness you had, Mother?"

"It was an affection of the lungs, dear. It was a constant cough, thatthreatened to turn to consumption, which is one of the most fataldiseases we have in England."

"But it hasn't cured you, Mother, for I often hear you coughing, atnight."

"Yes, my cough has been a little troublesome of late, Gregory."

Indeed, from the time of the disaster to the expedition of Hicks Pasha,Annie Hilliard had lost ground. She herself was conscious of it; but,except for the sake of the boy, she had not troubled over it. She hadnot altogether given up hope, but the hope grew fainter and fainter, asthe years went on. Had it not been for the promise to her husband, notto mention his real name or to make any application to his fatherunless absolutely assured of his death, she would, for Gregory's sake,have written to Mr. Hartley, and asked for help that would have enabledher to take the boy home to England, and have him properly educatedthere. But she had an implicit faith in the binding of a promise somade, and as long as she was not driven, by absolute want, to apply toMr. Hartley, was determined to keep to it.

A year after this conversation, Gregory was sixteen. Now tall andstrong, he had, for some time past, been anxious to obtain someemployment that would enable his mother to give up her teaching. Someof this, indeed, she had been obliged to relinquish. During the pastfew months her cheeks had become hollow, and her cough was now frequentby day, as well as by night. She had consulted an English doctor, who,she saw by the paper, was staying at Shepherd's Hotel. He had hesitatedbefore giving a direct opinion, but on her imploring him to tell herthe exact state of her health, said gently:

"I am afraid, madam, that I can give you no hope of recovery. One lunghas already gone, the other is very seriously diseased. Were you livingin England, I should say that your life might be prolonged by takingyou to a warm climate; but as it is, no change could be made for thebetter."

"Thank you, Doctor. I wanted to know the exact truth, and be able tomake my arrangements accordingly. I was quite convinced that mycondition was hopeless, but I thought it right to consult a physician,and to know how much time I could reckon on. Can you tell me that?"

"That is always difficult, Mrs. Hilliard. It may be three months hence.It might be more speedily--a vessel might give way in the lungs,suddenly. On the other hand, you might live six months. Of course, Icannot say how rapid the progress of the disease has been."

"It may not be a week, doctor. I am not at all afraid of hearing yoursentence--indeed, I can see it in your eyes."

"It may be within a week"--the doctor bowed his head gravely--"it maybe at any time."

"Thank you!" she said, quietly. "I was sure it could not be long. Ihave been teaching, but three weeks ago I had to give up my last pupil.My breath is so short that the slightest exertion brings on a fit ofcoughing."

On her return home she said to Gregory:

"My dear boy, you must have seen--you cannot have helped seeing--thatmy time is not long here. I have seen an English doctor today, and hesays the end may come at any moment."

"Oh, Mother, Mother!" the lad cried, throwing himself on his knees, andburying his face in her lap, "don't say so!"

The news, indeed, did not come as a surprise to him. He had, formonths, noticed the steady change in her: how her face had fallen away,how her hands seemed nerveless, her flesh transparent, and her eyesgrew larger and larger. Many times he had walked far up among the hillsand, when beyond the reach of human eye, thrown himself down and criedunrestrainedly, until his strength seemed utterly exhausted, and yetthe verdict now given seemed to come as a sudden blow.

"You must not break down, dear," she said quietly. "For months I havefelt that it was so; and, but for your sake, I did not care to live. Ithank God that I have been spared to see you growing up all that Icould wish; and though I should have liked to see you fairly started inlife, I feel that you may now make your way, unaided.

"Now I want, before it is too late, to give you instructions. In mydesk you will find a sealed envelope. It contains a copy of theregisters of my marriage, and of your birth. These will prove that yourfather married, and had a son. You can get plenty of witnesses who canprove that you were the child mentioned. I promised your father that Iwould not mention our real name to anyone, until it was necessary forme to write to your grandfather. I have kept that promise. His name wasGregory Hilliard, so we have not taken false names. They were hisChristian names. The third name, his family name, you will find whenyou open that envelope.

"I have been thinking, for months past, what you had best do; and thisis my advice, but do not look upon it as an order. You are old enoughto think for yourself. You know that Sir Herbert Kitchener, the Sirdar,is pushing his way up the Nile. I have no doubt that, with yourknowledge of Arabic, and of the language used by the black race in theSoudan, you will be able to obtain some sort of post in the army,perhaps as an interpreter to one of the officers commanding abrigade--the same position, in fact, as your father had, except thatthe army is now virtually British, whereas that he went with wasEgyptian.

"I have two reasons for desiring this. I do not wish you to go home,until you are in a position to dispense with all aid from your family.I have done without it, and I trust that you will be able to do thesame. I should like you to be able to go home at one-and-twenty, and tosay to your grandfather, 'I have not come home to ask for m

oney orassistance of any kind. I am earning my living honourably. I only askrecognition, by my family, as my father's son.'

"It is probable that this expedition will last fully two years. It mustbe a gradual advance, and even then, if the Khalifa is beaten, it mustbe a considerable time before matters are thoroughly settled. Therewill be many civil posts open to those who, like yourself, are wellacquainted with the language of the country; and if you can obtain oneof these, you may well remain there until you come of age. You can thenobtain a few months' leave of absence and go to England.

"My second reason is that, although my hope that your father is stillalive has almost died out, it is just possible that he is, like Neufeldand some others, a prisoner in the Khalifa's hands; or possibly livingas an Arab cultivator near El Obeid. Many prisoners will be taken, andfrom some of these we may learn such details, of the battle, as mayclear us of the darkness that hangs over your father's fate.

"When you do go home, Gregory, you had best go first to your father'sbrother. His address is on a paper in the envelope. He was heir to apeerage, and has, perhaps, now come into it. I have no reasons forsupposing that he sided with his father against yours. The brotherswere not bad friends, although they saw little of each other; for yourfather, after he left Oxford, was for the most part away from England,until a year before his marriage; and at that time your uncle was inAmerica, having gone out with two or three others on a huntingexpedition among the Rocky Mountains. There is, therefore, no reasonfor supposing that he will receive you otherwise than kindly, when oncehe is sure that you are his nephew. He may, indeed, for aught I know,have made efforts to discover your father, after he returned fromabroad."

"I would rather leave them alone altogether, Mother," Gregory saidpassionately.

"That you cannot do, my boy. Your father was anxious that you should beat least recognized, and afterwards bear your proper name. You will notbe going as a beggar, and there will be nothing humiliating. As to yourgrandfather, he may not even be alive. It is seldom that I see anEnglish newspaper, and even had his death been advertised in one of thepapers, I should hardly have noticed it, as I never did more than justglance at the principal items of news.

"In my desk you will also see my bank book. It is in your name. I havethought it better that it should stand so, as it will save a great dealof trouble, should anything happen to me. Happily, I have never had anyreasons to draw upon it, and there are now about five hundred and fiftypounds standing to your credit. Of late you have generally paid in themoney, and you are personally known to the manager. Should there be anydifficulty, I have made a will leaving everything to you. That sum willkeep you, if you cannot obtain the employment we speak of, until youcome of age; and will, at any rate, facilitate your getting employmentwith the army, as you will not be obliged to demand much pay, and cantake anything that offers.

"Another reason for your going to England is that your grandfather may,if he is dead, have relented at last towards your father, and may haveleft him some share in his fortune; and although you might well refuseto accept any help from him, if he is alive, you can have no hesitationin taking that which should be yours by right. I think sometimes now,my boy, that I have been wrong in not accepting the fact of yourfather's death as proved, and taking you home to England; but you willbelieve that I acted for the best, and I shrank from the thought ofgoing home as a beggar, while I could maintain you and myselfcomfortably, here."

"You were quite right, Mother dear. We have been very happy, and I havebeen looking forward to the time when I might work for you, as you haveworked for me. It has been a thousand times better, so, than living onthe charity of a man who looked down upon you, and who cast off myfather."

"Well, you will believe at least that I acted for the best, dear, and Iam not sure that it has not been for the best. At any rate I, too, havebeen far happier than I could have been, if living in England on anallowance begrudged to me."

A week later, Gregory was awakened by the cries of the Negro servant;and, running to Mrs. Hilliard's bedroom, found that his mother hadpassed away during the night. Burial speedily follows death in Egypt;and on the following day Gregory returned, heartbroken, to his lonelyhouse, after seeing her laid in her grave.

For a week, he did nothing but wander about the house, listlessly.Then, with a great effort, he roused himself. He had his work beforehim--had his mother's wishes to carry out. His first step was to go tothe bank, and ask to see the manager.

"You may have heard of my mother's death, Mr. Murray?" he said.

"Yes, my lad, and sorry, indeed, I was to hear of it. She was greatlyliked and respected, by all who knew her."

"She told me," Gregory went on, trying to steady his voice, "a weekbefore her death, that she had money here deposited in my name."

"That is so."

"Is there anything to be done about it, sir?"

"Not unless you wish to draw it out. She told me, some time ago, whyshe placed it in your name; and I told her that there would be nodifficulty."

"I do not want to draw any of it out, sir, as there were fifty poundsin the house. She was aware that she had not long to live, and no doubtkept it by her, on purpose."

"Then all you have to do is to write your signature on this piece ofpaper. I will hand you a cheque book, and you will only have to fill upa cheque and sign it, and draw out any amount you please."

"I have never seen a cheque book, sir. Will you kindly tell me what Ishould have to do?"

Mr. Murray took out a cheque book, and explained its use. Then he askedwhat Gregory thought of doing.

"I wish to go up with the Nile expedition, sir. It was my mother'swish, also, that I should do so. My main object is to endeavour toobtain particulars of my father's death, and to assure myself that hewas one of those who fell at El Obeid. I do not care in what capacity Igo up; but as I speak Arabic and Soudanese, as well as English, mymother thought that I might get employment as interpreter, either underan officer engaged on making the railway, or in some capacity under anofficer in one of the Egyptian regiments."

"I have no doubt that I can help you there, lad. I know the Sirdar, anda good many of the British officers, for whom I act as agent. Ofcourse, I don't know in what capacity they could employ you, but surelysome post or other could be found for you, where your knowledge of thelanguage would render you very useful. Naturally, the officers in theEgyptian service all understand enough of the language to get on with,but few of the officers in the British regiments do.

"It is fortunate that you came today. I have an appointment with LordCromer tomorrow morning, so I will take the opportunity of speaking tohim. As it is an army affair, and as your father was in the Egyptianservice, and your mother had a pension from it, I may get him tointerest himself in the matter. Kitchener is down here at present, andif Cromer would speak to him, I should think you would certainly beable to get up, though I cannot say in what position. The fact that youare familiar with the Negro language, which differs very widely fromthat of the Arab Soudan tribes, who all speak Arabic, is strongly inyour favour; and may give you an advantage over applicants who can onlyspeak Arabic.

"I shall see Lord Cromer at ten, and shall probably be with him for anhour. You may as well be outside his house, at half-past ten; possiblyhe may like to see you. At any rate, when I come down, I can tell youwhat he says."

With grateful thanks, Gregory returned home.

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates