- Home

- G. A. Henty

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Page 7

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Read online

Page 7

CHAPTER VI

A CITY MERCHANT

"Assuredly it is well that you should go," Sir Ralph said, when his sonhad repeated the conversation they had had with the trader. "I know notthe name, for indeed I know scarce one among the citizens; but if hetrades with Venice and Genoa direct he must be a man of repute andstanding. It is always well to make friends; and some of these citytraders could buy up a score of us poor knights. They are not men whomake a display of wealth, and by their attire you cannot tell one fromanother, but upon grand occasions, such as the accession or marriage ofa monarch, they can make a brave show, and can spend sums upon masquesand feastings that would well-nigh pay a king's ransom. After a greatvictory they will set the public conduits running with wine, and everyvarlet in the city can sit down at banquets prepared for them and eatand drink his fill. It is useful to have friends among such men. Theyare as proud in their way as are the greatest of our nobles, and theyhave more than once boldly withstood the will of our kings, and haveever got the best of the dispute."

"What shall we put on, sir," Albert asked his father the next morning,"for this visit to Master Gaiton?"

"You had better put on your best suits," the knight said; "it will showthat you have respect for him as a citizen, and indeed the dresses arefar less showy than many of those I see worn by some of the youngnobles in the streets."

"And what is the young lady like?" Aline asked her brother.

"Methinks she is something like you, Aline, and is about the same ageand height; her tresses are somewhat darker than yours; methinks she issomewhat graver and more staid than you are, as I suppose befits amaiden of the city."

"I don't think that you could judge much about that, Albert," hismother said, "seeing that, naturally, the poor girl was grievouslyshaken by the events of the evening before, and would, moreover, saybut little when her father was conversing with two strangers. Whatthought you of her, Edgar?"

"I scarce noticed her, my lady, for I was talking with her father, andso far as I remember she did not open her lips after being introducedto us. I did not notice the resemblance to your daughter that Albertspeaks of, but she seemed to me a fair young maid, who looked not, Iown, so heavy as she felt when I carried her."

"That is very uncourteous, Master Edgar," Dame Agatha laughed; "a goodknight should hold the weight of a lady to be as light as that of adown pillow."

"Then I fear that I shall never be a true knight," Edgar said, with asmile. "I have heard tales of knights carrying damsels across theirshoulder and outstripping the pursuit of caitiffs, from whom she hadescaped. I indeed had believed them, but assuredly either those talesare false or I have but a small share of the strength of which Ibelieved myself to be possessed; for, in truth, my arm and shoulderached by the time I reached the hostelry more than it has ever doneafter an hour's practice with the mace."

"Well, stand not talking," Sir Ralph said; "it is time for you tochange your suits, for these London citizens are, I have heard, preciseas to their time, and the merchant would deem it a slight did you notarrive a few minutes before the stroke of the hour."

As soon as they came into Chepe they asked a citizen if he could directthem to the house of Master Robert Gaiton.

"That can I," he said, "and so methinks could every boy and man in thecity. Turn to the right; his house stands in a courtyard facing theGuildhall, and is indeed next door to the hall in the left-hand corner."

The house was a large one, each storey, as usual, projecting over theone below it. Some apprentices were just putting up the shutters to theshop, for at noon most of the booths were closed, as at that hour therewere no customers, and the assistants and apprentices all took theirmeal together. There was a private entrance to the house, and Edgarknocked at the door with the hilt of his dagger. A minute later aserving-man opened it.

"Is Master Robert Gaiton within?" Albert asked. "He is, we believe,expecting us."

"I have his orders to conduct you upstairs, sirs."

The staircase was broad and handsome, and, to the lads' surprise, wascovered with an Eastern carpet. At the top of the stairs the merchanthimself was awaiting them.

"Welcome to my house, gentlemen," he said; "the house that would havebeen the abode of mourning and woe to-day, had it not been for yourbravery."

The merchant was dressed in very different attire to that in which hehad travelled. He wore a doublet of brown satin, and hose of the samematerial and colour; on his shoulders was a robe of Genoa velvet with acollar, and trimming down the front of brown fur, such as the boys hadnever before seen. Over his neck was a heavy gold chain, which theyjudged to be a sign of office. The landing was large and square, withrichly carved oak panelling, and, like the stairs, it was carpeted witha thick Eastern rug. Taking their hands, he led them through an opendoor into a large withdrawing-room. Its walls were panelled in asimilar manner to those of the landing, but the carpet was deeper andricher. Several splendid armoires or cabinets similarly carved stoodagainst the walls, and in these were gold and silver cups exquisitelychased, salt-cellars, and other silver ware.

The chairs were all in harmony with the room, the seats being of greenembossed velvet, and curtains of the same material and hue, with anedging of gold embroidery, hung at the windows. But the lads' eyescould not take in all these matters at once, being fixed upon the ladywho rose from her chair to meet them. She was some thirty-five yearsold, and of singular sweetness of face. There was but little about herof the stiffness that they had expected to find in the wife of a Londoncitizen. She was dressed in a loose robe of purple silk, with costlylace at the neck and sleeves. By her side stood Ursula, who wasdressed, as became her age, in lighter colours, which, in cut andmaterial, resembled those of Aline's new attire.

"Dear sirs," she said, as her husband presented the visitors to her,"with what words can I thank you for the service that you have renderedme. But for you I should have been widowed and childless to-day!"

"It was but a chance, Mistress Gaiton," Edgar said. "We saw a strangerin danger of his life from cut-throats, and as honest men should do, wewent to his succour. We are glad, indeed, to have been able to renderyour husband such service, but it was only such an action as a soldierperforms when he strikes in to rescue a comrade surrounded by theenemy, or carries off a wounded man who may be altogether a stranger tohim."

"That may be true from your point of view," the merchant said, "butjust as the man-at-arms rescued from a circle of foes, or the woundedman carried off the field would assuredly feel gratitude to him who hassaved him, so do we feel gratitude to you, and naught that you can saywill lessen our feeling towards you both. And now let us to the table."

He opened a door leading into another apartment. Edgar glanced atAlbert, and as he saw the latter was looking at Ursula, he offered hishand to Dame Gaiton. Albert, with a little start, did the same to thegirl. The merchant held aside the hangings of the door and thenfollowed them into the room where the table was laid. It was similar tothe room they had left, save that the floor was polished instead ofbeing carpeted. The table was laid with a damask cloth of snowywhiteness and of a fineness of quality such as neither of the lads hadever seen before. The napkins were of similar make. A great silverornament in the shape of a Venetian galley stood in the centre of thetable, flanked by two vases of the same metal filled with flowers. Theplates were of oriental porcelain, a contrast indeed to the roughearthenware in general use; the spoons were of gold.

The meats were carved at a side table, and cut into such pieces thatthere was little occasion for the use of the dagger-shaped knivesplaced for the use of each. Forks were unknown in Europe until nearlythree centuries later, the food being carried to the mouth by the aidof a piece of bread, just as it is still eaten in the East, the spoonbeing only used for soups and sweetmeats. Two servitors, attired indoublets of red and green cloth, waited. The wine was poured intogoblets of Venetian glass; and after several meats had been servedround, the lads were surprised at fresh plates being handed to them forthe

sweetmeats. Before these were put upon the table, a gold bowl withperfumed water was handed round, and all dipped their fingers in this,wiping them on their napkins.

"Truly, Mistress Gaiton," Albert said, courteously, "it seems to methat instead of coming to Court we country folk should come to the cityto learn how to live. All this is as strange to me as if I had gone tosome far land, by the side of whose people we were as barbarians."

"My husband has been frequently in Italy," she replied, "and he is muchenamoured of their mode of life, which he says is strangely in advanceof ours. Most of what you see here he has either brought with himthence, or had it sent over to him, or it has been made here fromdrawings prepared for him for the purpose. The carving of the wood-workis a copy of that in a palace at Genoa; the furniture came by sea fromVenice; the gold and silver work is English, for although my husbandsays that the Italians are great masters in such work and in advance ofour own, he holds that English gold and silversmiths can turn out workequal to all but the very best, and he therefore thinks it but right togive employment to London craftsmen. The drapery is far in advance ofanything that can be made here; as to the hangings and carpets,although brought from Genoa or Florence, they are all from Easternlooms."

"'Tis strange," the merchant added, "how far we are in most thingsbehind the Continent--in all matters save fighting, and, I may say, thecondition of the common people. Look at our garments. Save in thematter of coarse fabrics, nigh everything comes from abroad. The finestcloths come from Flanders; the silks, satins, and velvets from Italy.Our gold work is made from Italian models; our finest arms come fromMilan and Spain; our best brass work from Italy. Maybe some day weshall make all these things for ourselves. Then, too, our people--notonly those of the lowest class--are more rude and boorish in theirmanners; they drink more heavily, and eat more coarsely. An Englishbanquet is plentiful, I own, but it lacks the elegance and luxury ofone abroad, and save in the matter of joints, there is no comparisonbetween the cooking. Except in the weaving of the roughest linen, weare incomparably behind Flanders, France, or Italy, and although I havestriven somewhat to bring my surroundings up to the level of thecivilization abroad, the house is but as a hovel compared with thepalaces of the Venetian and Genoese merchants, or the rich traders ofFlanders and Paris."

"Truly, these must be magnificent indeed," Edgar said, "if they so farsurpass yours. I have never even thought of anything so comfortable andhandsome as your rooms. I say naught of those in my father's house, forhe is a scholar, and so that he can work in peace among his books andin his laboratory he cares naught for aught else; but it is the same inother houses that I have visited; they seem bare and cheerless by theside of yours. I have always heard that the houses of the merchants ofLondon were far more comfortable than the castles of great nobles, butI hardly conceived how great the difference was."

"They are built for different purposes," the merchant said. "Thecastles are designed wholly with an eye to defence. All is of stone,since that will not burn; the windows are mere slits, designed to shootfrom, rather than to give light. We traders, upon the other hand, havenot to spend our money on bands of armed retainers. We have our citywalls, and each man is a soldier if needs be. Then our intercourse withforeign merchants and our visits to the Continent show us what othersare doing, and how vastly their houses are ahead of ours in point ofluxury and equipment. We have no show to keep up; and, at any rate,when we go abroad it is neither our custom nor that of the Flemishmerchants to vie with the nobility in splendour of apparel or themultitude of retainers and followers. Thus, you see, we can afford tohave our homes comfortable."

"May I ask, Master Gaiton, if your robe and chain are badges ofoffice?" Albert asked.

"Yes; I have the honour of being an alderman."

Albert looked surprised. "I thought, sir, that the aldermen were agedmen."

"Not always," the merchant said, with a smile, "though generally thatis the case. The aldermen are chosen by the votes of the Common Councilof each ward, and that choice generally falls upon one whom they deemwill worthily represent them, or upon one who shows the most devotionto the interests of the ward and city. My father was a prominentcitizen before me, and I early learned from him to take an interest inthe affairs of the city. It chanced that, when on the accession of theyoung king the Duke of Lancaster would have infringed some of ourrights and privileges, I was one of the speakers at a meeting of thecitizens, and being younger and perhaps more outspoken than others, Icame to be looked upon as one of the champions of the city, and thus,without any merit of my own, was elected to represent my ward when avacancy occurred shortly afterwards."

"My husband scarce does himself justice, Master De Courcy," thetrader's wife said, "for it was not only because of his championship ofthe city's rights, but as one of the richest and most enterprising ofour merchants, and because he spends his wealth worthily, giving largegifts to many charities, and being always foremost in every work forthe benefit of the citizens. Maybe, too, the fact that he was one ofthe eight citizens who jousted at the tournament, given at the king'saccession, against the nobles of the Court, and who overthrew hisadversary, had also something to do with his election."

"Nay, nay, wife! these are private affairs that are of little interestto our guests, and you speak with partiality."

"At any rate, sir," Edgar said, courteously, "the fact that you so boreyourself in the tournament suffices to explain how it was that you wereable to keep those cut-throats at bay until just before we arrived atthe spot."

"We are peaceful men in the city," the merchant said, "but we know thatif we are to maintain our rights, and to give such aid as behoves us toour king in his foreign wars, we need knowledge as much as others howto bear arms. Every apprentice as well as every free man throughout thecity has to practise at the butts, and to learn to use sword anddagger. I myself was naturally well instructed; and as my father waswealthy, there were always two or three good horses in his stables, andI learned to couch a lance and sit firm in the saddle. As at Hastingsand Poictiers, the contingent of the city has ever been held to bearitself as well as the best; and although we do not, like most men,always go about the street with swords in our belts, we can all usethem if needs be. Strangely enough, it is your trading communities thatare most given to fighting. Look at Venice and Genoa, Milan and Pisa,Antwerp, Ghent, and Bruges, and to go further back, Carthage and Tyre.And even among us, look at the men of Sandwich and Fowey in Cornwall;they are traders, but still more they are fighters; they are everharassing the ships of France, and making raids on the French coast."

"I see that it is as you say," Edgar said, "though I have never thoughtof it before. Somehow one comes to think of the citizens of great townsas being above all things peaceful."

"The difference between them and your knights is, that the latter arealways ready to fight for honour and glory, and often from the purelove of fighting. We do not want to fight, but are ready to do so forour rights and perhaps for our interests, but at bottom I believe thatthere is little difference between the classes. Perhaps if weunderstood each other better we should join more closely together. Weare necessary to each other; we have the honour of England equally atheart. The knights and nobles do most of our fighting for us, while we,on our part, import or produce everything they need beyond the commonnecessities of life; both of us are interested in checking the undueexercise of kingly authority; and if they supply the greater part ofthe force with which we carry on the war with France, assuredly it iswe who find the greater part of the money for the expenses, while weget no share of the spoils of battle."

"Have you any sisters, Master De Courcy?" the merchant's wife asked,presently.

"I have but one; she is just about the same age as your daughter, andmethinks there is a strong likeness between them. She and my mother areboth here, having been sent for by my father on the news of thetroubles in our neighbourhood."

"In that case, wife," the merchant said, "it were seemly that you andUrsula accompany me to-morro

w when I go to pay my respects to Sir RalphDe Courcy."

After dinner was over the merchant took his guests into a small roomadjoining that in which they had dined.

"Friends," he said, "we London merchants are accustomed to express ourgratitude not only by words but by deeds. At present, methinks, seeingthat, as you have told me, you have not yet launched out into theworld, there is naught that you need; but this may not be so always,for none can tell what fortune may befall him. I only say that anyservice I can possibly render you at any time, you have but to ask me.I am a rich man, and, having no son, my daughter is my only heir. Hadyour estate been different and your taste turned towards trade, I couldhave put you in the way of becoming like myself, foreign merchants; buteven in your own profession of arms I may be of assistance.

"Should you go to the war later on and wish to take a strong followingwith you, you have but to come to me and say how much it will cost toarm and equip them and I will forthwith defray it, and my pleasure indoing so will be greater than yours in being able to follow the kingwith a goodly array of fighting men. One thing, at least, you mustpermit me to do when the time comes that you are to make your firstessay in arms: it will be my pleasure and pride to furnish you withhorse, arms, and armour. This, however, is a small matter. What Ireally wish you to believe is that under all circumstances--and onecannot say what will happen during the present troubles--you can relyupon me absolutely."

"We thank you most heartily, sir," Edgar said, "and should the timecome when, as you say, circumstances may occur in which we can takeadvantage of your most generous offers, we will do so."

"That is well and loyally said," the merchant replied, "and I shallhold you to it. You will remember that, by so doing, it will be you whoconfer the favour and not I, for my wife and I will always be uneasy inour minds until we can do something at least towards proving ourgratitude for the service that you have rendered."

A few minutes later, after taking leave of the merchant's wife anddaughter, the two friends left the house.

"Truly we have been royally entertained, Edgar. What luxury andcomfort, and yet everything quiet and in good taste. The apartments ofthe king himself are cold and bare in comparison. I felt half inclinedto embrace his offer and to declare that I would fain become a traderlike himself."

Edgar laughed, "Who ever heard of such a thing as the son of a valiantknight going into trade? Why the bare thought of such a thing wouldmake Sir Ralph's hair stand on end. You would even shock your gentlemother."

"But why should it, Edgar? In Italy the nobles are traders, and no onethinks it a dishonour. Why should not a peaceful trade be held in ashigh esteem as fighting?"

"That I cannot say, Albert," Edgar replied, more seriously; "butwhatever may be the case in Venice, it assuredly is not so here. It maybe that some day when we reach as high a civilization as Genoa andVenice possess, trade may here be viewed as it is there--as honourablefor even those of the highest birth. Surely commerce requires far morebrains and wisdom than the dealing of blows, and the merchants ofVenice can fight as earnestly as they can trade. Still, no one man canstand against public opinion, and until trade comes to be generallyviewed as being as honourable a calling as that of war, men of gentleblood will not enter upon it; and you must remember, Albert, that it isbut the exceptions who can gain such wealth as that of our host to-day,and that had you gone into the house of one of the many who can onlyearn a subsistence from it, you would not have been so entertained.But, of course, you are not serious, Albert."

"Not serious in thinking of being a trader, Edgar, though methinks thelife would suit me well; but quite serious in not seeing why knightsand nobles should look down upon traders."

"There I quite agree with you; but as my father said to me, 'You mustnot think, Edgar, that you can set yourself up and judge othersaccording to your own ideas.' We were especially speaking then of thefreeing of the serfs and the bettering of their condition. 'Thesethings,' he said, 'will come assuredly when the general opinion is ripefor them, but those who first advocate changes are ever looked upon asdreamers, if not as seditious and dangerous persons, and to force on athing before the world is fit for it is to do harm rather than good.Theoretically, there is as much to be said for the views of the priestJack Straw and other agitators, as for those of Wickcliffe; but theiropinions will at first bring persecution and maybe death to those whohold them. These peasants will rise in arms, and will, when the affairis over--should they escape with their lives--find their condition evenworse than before; while the followers of Wickcliffe will have thewhole power of the Church against them, and may suffer persecution andeven death, besides being often viewed with grave disfavour even bytheir families for taking up with strange doctrines.'"

"No doubt that is so, Edgar, but I wish I lived in days when it werenot deemed necessary that one of gentle blood should be either afighting man or a priest."

In the time of Richard II. it was not considered in any waymisdemeaning to receive a present for services rendered--a chain ofgold, arms and armour, and even purses of money were so received withas little hesitation as were ransoms for prisoners taken in battle.Therefore Sir Ralph expressed himself as much pleased when he heard ofthe merchant's promise to present their military outfit to the twolads, and of his proffer of other services.

"By St. George," he said, "such good fortune never befell me, althoughI have been fighting since my youth. I have, it is true, earned many aheavy ransom from prisoners taken in battle, but that was a matter ofbusiness. The gold chain I wear was a present from the Black Prince,and I do not say that I have not received some presents in my time frommerchants whose property I have rescued from marauders, or to whom Ihave rendered other service. Still, I know not of any one piece of goodfortune that equals yours, and truly I myself have no smallsatisfaction in it, for I have wondered sometimes where the sums wouldhave come from to furnish Albert with suitable armour and horse, whichhe must have if he is to ride in the train of a noble. In truth, Ishall be glad to see this merchant of yours, and maybe his daughterwill be a nice companion for Aline, who, not having her own pursuitshere, finds it, methinks, dull. Just at present the Court has otherthings to think of besides pleasure."

On the following day the visit was paid, and afforded pleasure to allparties. The knight was pleased with the manners of the merchant, who,owing to his visit to Italy, had little of the formal gravity of hiscraft, while there was a heartiness and straightforwardness in hisspeech that well suited the bluff knight. The ladies were no lesspleased with each other, and Dame Agatha found herself, to hersurprise, chatting with her visitors on terms of equality, anddiscoursing on dress and fashion, the doings of the Court and life inthe city, as if she had known her for years. At her mother's suggestionAline went with Ursula into the garden, and from time to time theirmerry laughter could be heard through the open window.

"I hope that you will allow your daughter to come and see minesometimes," the dame said, as her guest rose to leave. "When at homethe girl has her horse and dogs, her garden, and her household dutiesto occupy her. Here she has naught to do save to sit and embroider, andto have a girl friend would be a great pleasure to her."

"Ursula will be very glad to do so, and I trust that you will allowyour daughter sometimes to come to us. I will always send her backunder good escort."

Every day rendered the political situation more serious. The Kentishrising daily assumed larger proportions, and was swollen by a greatnumber of the Essex men, who crossed the river and joined them; and onemorning the news came that a hundred thousand men were gathered onBlackheath, the Kentish men having been joined not only by those ofEssex, but by many from Sussex, Herts, Cambridge, Suffolk, and Norfolk.These were not under one chief leader, but the men from each localityhad their own captain. These were Wat the Tyler, William Raw, JackSheppard, Tom Milner, and Hob Carter.

"Things are coming to a pass indeed," Sir Ralph said, angrily, as hereturned from the Tower late one afternoon. "What think you, thisrabble has

had the insolence to stop the king's mother, as with herretinue she was journeying hither. Methought that there was not anEnglishman who did not hold the widow of the Black Prince in honour,and yet the scurvy knaves stopped her. It is true that they shouted agreeting to her, but they would not let her pass until she hadconsented to kiss some of their unwashed faces. And, in faith, seeingthat her life would have been in danger did she refuse, she was forcedto consent to this humiliation.

"By St. George, it makes my blood boil to think of it; and here, whilesuch things are going on, we are doing naught. Even the city does notcall out its bands, nor is there any preparation made to meet thestorm. All profess to believe that these fellows mean no harm, and willbe put off with a few soft words, forgetful of what happened in Francewhen the peasants rose, and that these rascals have already put todeath some score of judges, lawyers, and wealthy people. However, whenthe princess arrived with the news, even the king's councillorsconcluded that something must be done, and I am to ride, with fiveother knights, at six to-morrow morning, to Blackheath, to ask theserascals, in the name of the king, what it is that they would have, andto promise them that their requests shall be carefully considered."

At nine the next morning the knight returned.

"What news, Sir Ralph?" Dame Agatha asked, as he entered. "How have yousped with your mission?"

"In truth, we have not sped at all. The pestilent knaves refused tohave aught to say to us, but bade us return and tell the king that itwas with him that they would have speech, and that it was altogetheruseless his sending out others to talk for him; he himself must come.'Tis past all bearing. Never did I see such a gathering of raggedrascals; not one of them, I verily believe, has as much as washed hisface since they started from home. I scarce thought that all Englandcould have turned out such a gathering. Let me have some bread andwine, and such meat as you have ready. There is to be a council in halfan hour, and I must be there. There is no saying what advice some ofthese poor-spirited courtiers may give."

"What will be your counsel, Sir Ralph?"

"My counsel will be that the king should mount with what knights he mayhave, and a couple of score of men-at-arms, and should ride to Oxford,send out summonses to his nobles to gather there with their vassals,and then come and talk with these rebels, and in such fashion as theycould best understand. They may have grievances, but this is not theway to urge them, by gathering in arms, murdering numbers of honourablemen, insulting the king's mother, burning deeds and records, and nowdemanding that the king himself should wait on their scurvy majesties.Yet I know that there will be some of these time-servers round the kingwho will advise him to intrust himself to these rascals who haveinsulted his mother.

"By my faith, were there but a couple of score of my old companionshere, we would don our armour, mount our warhorses, and ride at them.It may be that we should be slain, but before that came about we wouldmake such slaughter of them that they would think twice before theytook another step towards London."

"It was as I expected," the knight said, when he returned from thecouncil. "The majority were in favour of the king yielding to theseknaves and placing himself in their power, but the archbishop ofCanterbury, and Hales the treasurer, and I, withstood them so hotlythat the king yielded to us, but not until I had charged them withtreachery, and with wishing to imperil the king's life for the safetyof their own skins. De Vere and I might have come to blows had it notbeen for the king's presence."

"Then what was the final decision of the council, Sir Ralph?" his wifeasked.

"It was a sort of compromise," the knight said. "One which pleased menot, but which at any rate will save the king from insult. He will senda messenger to-day to them saying that he will proceed to-morrow in hisbarge to Rotherhithe, and will there hold converse with them. Heintends not to disembark, but to parley with them from the boat, and hewill, at least in that way, be safe from assault. I hear that anothergreat body of the Essex, Herts, Norfolk, and Suffolk rebels havearrived on the bank opposite Greenwich, and that it is their purpose,while those of Blackheath enter the city from Southwark, to marchstraight hitherwards, so that we shall be altogether encompassed bythem."

"But the citizens will surely never let them cross the bridge?"

"I know not," the knight said, gloomily. "The lord mayor had audiencewith the king this morning, and confessed to him that, although he andall the better class of citizens would gladly oppose the rioters to thelast, and suffer none to enter the walls, that great numbers of thelower class were in favour of these fellows, and that it might be thatthey would altogether get the better of them, and make common causewith the rabble. Many of these people have been out to Blackheath; somehave stayed there with the mob, while others have brought back news oftheir doings. Among the rabble on Blackheath are many hedge priests;notably, I hear, one John Ball, a pestilent knave, who preaches treasonto them, and tells them that as all men are equal, so all the goods ofthose of the better class should be divided among those having nothing,a doctrine which pleases the rascals mightily."

The next day, accordingly, the king went down with some of hiscouncillors to Rotherhithe. A vast crowd lined both banks of the river,and saluted him with such yells and shouts, that those with him,fearing the people might put off in boats and attack him, bade therowers turn the boat's head and make up the river again; and,fortunately, the tide being just on the turn, they were thus able tokeep their course in the middle of the river, and so escape any arrowsthat might otherwise have been shot at them.

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

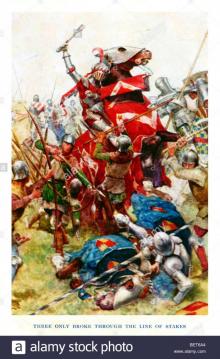

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates