- Home

- G. A. Henty

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Page 7

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Read online

Page 7

CHAPTER VII

A SKIRMISH

They started at once, not trying to mount the hillside above the pointwhere they had been hidden, but to keep along as far as possible atthe same height. After making their way painfully for a couple ofhours, they came to a spot from which they could see the valley belowthem. They then gradually made their way down till only two or threehundred feet above its bottom, and then kept along its side. In thestill night air they could hear many voices, and knew that the comingof these mysterious and dangerous visitors was being warmly discussed.Lights burned much later than was usual in the villages, but at lastthese altogether disappeared, and they ventured still lower, keeping,however, a sharp look-out for any villages situated on the spurs. Thevalley was not above eight or ten miles long, and they were well pastit before morning dawned.

The country they now entered was a little more precipitous and ruggedthan that they had recently passed, and they agreed that it would beimpossible to climb over it, and that they would have to make use ofthe pass. They therefore chose a good hiding-place some distance up onthe hill. It was sheltered from behind by a precipice, at whose footgrew a clump of bushes of considerable size.

"We cannot do better than this," Carter said, "and as the people willbe starting in search of us in less than an hour we have no farthertime to look for another hiding-place, and, indeed, I don't thinkthat we should be likely to find a better one if we did. There is onecomfort: however numerously they turn out, they will take care not toscatter much, in view of the lesson you gave them, and unless they doscatter, their chance of lighting upon us is small indeed. I don'tsuppose their heart will be very much in the business, except on thepart of the relatives of the men you shot, who are, after all, aslikely to belong to the valley we left as to this one. These tribesmenare good fighters when their liberty is threatened, but they are notvery fond of putting themselves into danger.

"I feel much more comfortable," Carter continued, "now I am no longercondemned to go about unarmed. It was a grand idea taking the rifles ofthose two men we shot. The pony carries one, and I carry the other."

"But you have carried one all the time."

"Yes, but as I was under orders to hand it over to you whenever youwanted it, it has not been any great satisfaction to me. Now I can feelthat I can play my part, and although these Martinis are not quite asgood as your Lee-Metford, they are quite good enough for all practicalpurposes, and with your magazine always in readiness we ought to beable to give a good account of ourselves."

The day passed quietly. Parties of men were seen moving about on thehills, but none came near them. At night they went forward again, butmoved with great caution, as it was possible that as fugitives couldhardly get across the mountains the Afridis might keep a watch in thepass. They had crossed the highest point, and were descending, whenthey saw rising before them, by the side of the path, an old Buddhisttemple. When within a short distance from it half a dozen men jumpedout and fired a volley. The shots all went wide, but the reply was notso futile. Four men fell, and the rest, appalled by the heavy loss,fled down the hill.

"That is sharp," Carter said, "but soon over. However, this is but thebeginning of it; they will carry the news down to the next valley, andwe shall be besieged here. However, fortunately, it appears to be verysteep on both sides of the temple, and I don't think even the Afridis,firm-footed as they are, will be able to climb the hill and get behindus."

"But we can no more get up than they can."

"No, but at least it will give us only one side to defend, and we cankeep an eye on the hills and pick off any who try to make their wayalong the top, and if the worst comes to the worst we must retire downthe pass again to-night, and try to strike out somewhere over thehills. It doesn't much matter which way so that we get out of thisneighbourhood, which is becoming altogether too hot for us."

Daylight was just breaking when a number of men were seen coming up thepass. The two fugitives had already ensconced themselves and their ponyin the temple, and had posted themselves at two of the narrow windows.Nita shouted, "Keep away, or it will be worse for you. We don't wantto hurt you, if you will leave us alone, but if you attack us we shalldefend ourselves."

The answer was a volley of shots, to which the defenders of thetemple did not reply, as they were anxious not to waste a cartridge.Emboldened by the silence, the enemy gradually approached, keeping up asteady fire. When they were within eighty yards the defenders answeredsteadily and deliberately. By the time twenty rounds had been fired theenemy were in full flight, leaving six dead upon the ground, whileseveral of the others were wounded.

"I expect that will sicken them effectually," Carter said, "and that,at any rate, they will not attempt to renew the attack until it becomesdark again. I think we had better wait an hour and see what they intenddoing."

The hour was just up when a white figure was seen high up on thehillside, making his way cautiously along the face of the precipitoushill.

"What is the distance, do you think?" Carter said.

"Five to six hundred yards, I should say."

"I suppose it is about that. Well, he must be stopped if possible."And, levelling his rifle, he took a long steady aim and fired. The manwas seen to start as the bullet sung up close to him. "You can beatthat, Nita," he said in a tone of disgust.

"I will try, anyhow," she said, "but the range puzzles one, the manbeing so far above us." She steadied her rifle against a stone andfired. The man was seen to disappear behind a rock.

"A splendid shot!" Carter exclaimed.

"I am not sure that I hit him, I think he fell at the flash. However,there is a space between that stone and the boulder ahead of it."

It was five minutes before any movement was seen, then the man startedforward suddenly. Nita was kneeling with her rifle aimed at a spothalf-way between the stones, and as he crossed she pressed the trigger.This time there was no mistake; the man fell forward on his face andlay there immovable.

"I have no doubt that they are watching down below, and when they seehim fall no one will care to follow his example. Now I think we hadbetter be moving. We must risk meeting people coming over the pass.If we can get over the worst of it, we must hide and then climb themountain, on whichever side appears easiest."

No time was lost. It was still early, for daylight was scarcelybreaking when the attack had taken place. Leaving the temple theystarted at once, travelling as fast as the pony could pick its wayalong the steep path. Two hours later they saw, far in the distance,two men coming up. There was fortunately some shelter near, and herethey took refuge and lay hidden until the men had passed them, andthen continued their journey. They were three parts of the way downthe pass, when on their right-hand side they saw a slope that seemedpracticable, and they made their way up slowly and cautiously till theyreached a plateau, the mountain still rising steeply in front of them.They travelled along this plateau, and presently saw an opening in themountain range. They halted now, lit a fire in a hollow, and cookedsome food, and then, confident that they were well beyond the arealikely to be searched, they lay down to sleep.

A start was made at daybreak. They found the difficulty of crossing therange enormous, and had frequently to retrace their steps, but at laststruck the head of a small ravine and decided to follow it down. Latein the evening they found themselves at a spot where the ravine widenedinto a valley. They waited until morning, when they were able to obtaina view down this. It was of no very great extent--about a quarter of amile wide and half a mile long, and contained but a few houses. Theyremained quiet all day, and at nightfall moved along the valley onthe side opposite to the village. They found that a small stream ranthrough it, and they decided to follow its course, the next morninghalting well beyond the valley in a deep gorge.

"It is strange," Nita said, as they settled themselves for a rest, "howthese narrow gorges can have cut their way through the mountains."

"Yes; it ca

n only be that ages since these valleys were all deep lakes.At the time of the melting of the snows they overflowed. No doubt insome places the strata were softer than others, and here the waterbegan to cut a groove, which grew deeper and deeper till at last thelake was empty. Then of course the work stopped and the water wouldrun off as fast as it fell."

"It must have taken an enormous time," Nita said, "for the hillsbordering the ravines must in some places be three or four thousandfeet deep."

"Fully that. It certainly gives us a wonderful idea of the age of theworld, and the tremendous power exercised by water; in dry weatherthese ravines formed the chief roads of the country, though some, nodoubt, are so blocked with boulders fallen from above, or washed downby torrents, that they cannot be used by laden animals. I fancy thereis not much communication between the valleys. They are governed bytheir chiefs, and it is only in cases of common danger that they everact together. They prize their independence above everything, and areready to gather from all parts of the country for common defence. NoEuropean except ourselves, I feel certain, has ever entered thesevalleys, and the inhabitants are absolutely convinced that theirravines and passes are impregnable. No doubt at some time or otherthe British will be driven to send an expedition to convince them tothe contrary. I think that if there were no such things as guns theirbelief in their impregnability would be well justified. The men arebrave and hardy, and thoroughly understand how to take advantage ofthe wonderful facilities of their ground for defence, and even inthe most remote valleys they have managed to accumulate a store offirst-rate rifles.

"How they have got them is a mystery. A good many, perhaps, have beencarried off by deserters from our frontier regiments. Many of theseenlist for this purpose alone. They serve faithfully for a time, butat the first opportunity make off with their rifle. Still, numerousas these desertions are, they would not account for a tithe of therifles in the hands of the tribesmen. Some, I fancy, must be landedby rascally British dealers, in the Persian Gulf, or on the coast ofBeluchistan. Some have been imported by traders from India. At any rateit is unquestionable that a vast number of rifles are in the hands ofthe Afridis, and will give us a world of trouble when we set ourselvesin earnest to deprive them of them."

"I wonder the government doesn't forbid the exportation of riflesaltogether," Nita said indignantly.

"It would be well if they did so, but there are difficulties inthe way. The Indian princes buy them in large quantities for theirfollowers, and nominally they are no doubt imported for that purpose,but when well up country they are taken north and disposed of to theAfridis, who are ready to pay any price for them, for an Afridi valuesnothing as he does a good rifle, and he would willingly exchange wifeor child to get possession of one."

"But nobody wants to buy a wife or child," Nita said. "It doesn't seemto me that they possess any sort of property that could pay for therifles by the time they got into the country."

"I fancy they are paid for largely in cattle. Herds are driven down thecountry, and no watch that we can keep can prevent the traffic. Thecattle are always consigned to some large town well past the frontier,where the rifles can easily be handed over."

"I think it ought to be stopped altogether," Nita said indignantly;"the people of the towns can do very well without Afridi cattle, and ifnot, they should be made to. It would be much better for them to haveto pay an anna extra a pound for their meat, than for us to have tospend hundreds of lives and millions of pounds in getting the riflesback again."

"Yes, there are many things that we soldiers, who are only here to dothe fighting, can make neither head nor tail of. If India were governedby soldiers instead of civilians, things would be very differentlymanaged. As it is, we can only wonder and grumble. The authorities areso mightily afraid of injuring the susceptibilities of the nativesthat they pamper them in every way, and even when it is manifest thatthe whole of the community suffer by their so doing. It is the moreridiculous, because, in the old days, their own rulers paid not theslightest attention to these same susceptibilities, or to the likes ordislikes of their subjects."

"It is all very strange," Nita said, "and very unaccountable."

"Everyone on the frontier knows that sooner or later we shall have todeal with the Afridis, and that it will be an enormously difficult andexpensive business, and will cost an immense amount of life."

"Don't let us talk about it any more; it makes me out of all patienceto think of such folly."

The journey was resumed the next morning, and continued day afterday and week after week. Sometimes they were obliged to turn quiteout of their direct course, and they had to run considerable risksto get fresh supplies for themselves and forage for the pony. Bothwere obtained by entering villages at night, and filling their sackfrom stacks of grain and forage. The grain they pounded between flatstones as they sat by their fire, and so made a coarse meal whichthey generally boiled into a sort of porridge, their sauce-pans beinggourds cut in the fields. Meat they had no difficulty about, as Cartermanaged, when necessary, to kill a bullock and take sufficient meat forten days' supply.

They seldom caught sight of a villager when travelling through thevalleys, for the Afridis have a marked objection to moving about afternightfall. Once or twice one or two of them approached them, butCarter raised such a loud and threatening roar, that they in each caseretreated with all speed to their village, which they filled with alarmwith tales of having encountered strange and terrible creatures.

Gradually the difficulties decreased, the mountains became lessprecipitous, the valleys larger and more thickly inhabited, a matterwhich caused them no inconvenience as they always traversed them atnight. During their journey Carter had filled Nita's note-book withsketches and maps, which, as the country was wholly unexplored, wouldbe of great advantage to an advancing army when properly copied outon a large scale. He was clever with his pencil, and Nita used to begreatly interested in his lively little sketches of the scenery throughwhich they passed.

"It will be very useful to me," he said; "and in the event of troopshaving to march through this district, should go a long way towardssecuring me a staff appointment, for in such a case these sketches andmaps would be invaluable, and I should get no end of credit for them."

"So you ought to," Nita said; "you have taken a lot of pains aboutthem, and anyone with those maps should be able to find their way backby the route we have come."

"I have my doubts about that," he said; "that is, if I were not withthem to point out the places we have passed. I should find it difficultmyself, for we have come by a very devious road. Of course, I have hadno chance whatever of getting compass bearings, and have only been ableto put them in by the position of the sun. And besides, a great part ofour journey has been done by night. Although, of course, I can indicatethe general direction of the valleys through which we have passed, ourroutes at night among the mountains are necessarily little more thanguesswork, for except when we had the moon we have practically nothingelse to tell us of our position, or the direction in which we weregoing."

"We had the stars," Nita said.

"Yes, when I get back and work out the position of the stars it will,of course, help me a great deal, and the pole-star especially has beenof immense use to us. In fact, had it not been for that star we shouldnot, except when there was a moon, have been able to travel."

"I am sure it will all come right when you work it out," Nita saidconfidently, "and that you will get an immense deal of credit for it.It has been a jolly time, hasn't it, in spite of the hard work andthe danger? I know that I have had a capital time of it; and as to myhealth, I feel as strong as a horse, and fit to walk any distance,especially since my feet have got so hard."

"It is a time that I shall always look back upon, Nita, as one of mymost pleasant memories. You have been such a splendid comrade, thanksto your pluck and good spirits, and no words can express how much Ifeel indebted to you."

"Oh, that is all nonsense!" she said; "of course I have done my best

,but that was very little."

"You may not think so, but in reality I owe you not only my escape, andthe various suggestions which have been of so much use to us, as, forexample, our hiding in that place close to the road instead of startingup into the hills, where we should have certainly been overtaken; butyou have helped on many another occasion too, to say nothing of theconstant cheeriness of your companionship. It has certainly been verystrange, a young man and a girl thus wandering about together, butsomehow it has scarcely felt strange to me. The defence of the fortbrought us very close to each other, and was so far fortunate thatit prepared us for this business. However, I agree most thoroughlywith you, that in spite of the hardships and dangers we have had to gothrough, our companionship has been a very pleasant one."

"Oh, dear!" Nita sighed; "how disgusting it will be to have to put ongirl's clothes again, and settle down into being stiff and proper!Fancy having to learn school lessons again after all this."

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

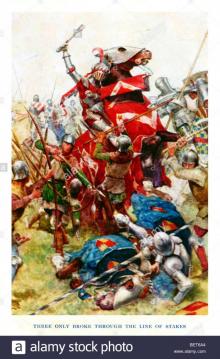

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

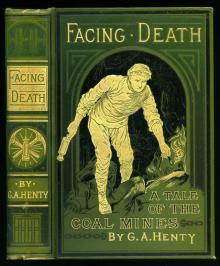

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

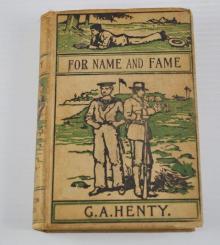

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

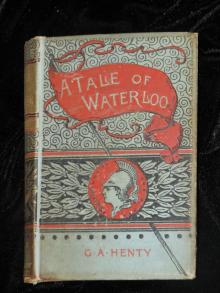

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

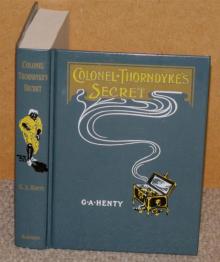

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

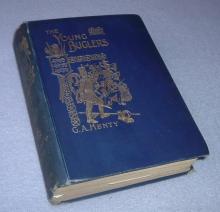

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates