- Home

- G. A. Henty

A Jacobite Exile Page 8

A Jacobite Exile Read online

Page 8

Chapter 8: The Passage of the Dwina.

A few hours after Charlie's arrival home, Major Jervoise and Harrycame round to the house.

"I congratulate you, Jervoise, on your new rank," Sir Marmadukesaid heartily, as he entered; "and you, too, Harry. It has been agreat comfort to me, to know that you and Charlie have beentogether always. At present you have the advantage of him in looks.My lad has no more strength than a girl, not half the strength,indeed, of many of these sturdy Swedish maidens."

"Yes, Charlie has had a bad bout of it, Carstairs," Major Jervoisesaid cheerfully; "but he has picked up wonderfully in the last tendays, and, in as many more, I shall look to see him at work again.I only wish that you could have been with us, old friend."

"It is of no use wishing, Jervoise. We have heard enough here, ofwhat the troops have been suffering through the winter, for me toknow that, if I had had my wish and gone with you, my bones wouldnow be lying somewhere under the soil of Livonia."

"Yes, it was a hard time," Major Jervoise agreed, "but we all gotthrough it well, thanks principally to our turning to at sports ofall kinds. These kept the men in health, and prevented them frommoping. The king was struck with the condition of our company, andhe has ordered that, in future, all the Swedish troops shall takepart in such games and amusements when in winter quarters. Ofcourse, Charlie has told you we are going to have a regimententirely composed of Scots and Englishmen. I put the Scots first,since they will be by far the most numerous. There are alwaysplenty of active spirits, who find but small opening for theirenergy at home, and are ready to take foreign service whenever thechance opens. Besides, there are always feuds there. In the olddays, it was chief against chief. Now it is religion againstreligion; and now, as then, there are numbers of young fellows gladto exchange the troubles at home for service abroad. There havebeen quite a crowd of men round our quarters, for, directly thenews spread that the company was landing, our countrymen flockedround, each eager to learn how many vacancies there were in theranks, and whether we would receive recruits. Their joy was extremewhen it became known that Jamieson had authority to raise a wholeregiment. I doubt not that many of the poor fellows are in greatstraits."

"That I can tell you they are," Sir Marmaduke broke in. "We havebeen doing what we can for them, for it was grievous that so manymen should be wandering, without means or employment, in a strangecountry. But the number was too great for our money to go far amongthem, and I know that many of them are destitute and well-nighstarving. We had hoped to ship some of them back to Scotland, andhave been treating with the captain of a vessel sailing, in two orthree days, to carry them home."

"It is unfortunate, but they have none to blame but themselves.They should have waited until an invitation for foreigners toenlist was issued by the Swedish government, or until gentlemen ofbirth raised companies and regiments for service here. However, weare the gainers, for I see that we shall not have to wait here manyweeks. Already, as far as I can judge from what I hear, there mustbe well-nigh four hundred men here, all eager to serve.

"We will send the news by the next ship that sails, both toScotland and to our own country, that men, active and fit forservice, can be received into a regiment, specially formed ofEnglish-speaking soldiers. I will warrant that, when it is known inthe Fells that I am a major in the regiment, and that your son andmine are lieutenants, we shall have two or three score of stoutyoung fellows coming over."

The next day, indeed, nearly four hundred men were enlisted intothe service, and were divided into eight companies. Each of these,when complete, was to be two hundred strong. Six Scottish officerswere transferred, from Swedish regiments, to fill up the list ofcaptains, and commissions were given to several gentlemen of familyas lieutenants and ensigns. Most of these, however, were held over,as the colonel wrote to many gentlemen of his acquaintance inScotland, offering them commissions if they would raise and bringover men. Major Jervoise did the same to half a dozen youngJacobite gentlemen in the north of England, and so successful werethe appeals that, within two months of the return of the company toGottenburg, the regiment had been raised to its full strength.

A fortnight was spent in drilling the last batch of recruits, frommorning till night, so that they should be able to take theirplaces in the ranks; and then, with drums beating and coloursflying, the corps embarked at Gottenburg, and sailed to join thearmy.

They arrived at Revel in the beginning of May. The port was full ofships, for twelve thousand men had embarked, at Stockholm and otherports, to reinforce the army and enable the king to take the fieldin force; and, by the end of the month, the greater portion of theforce was concentrated at Dorpt.

Charlie had long since regained his full strength. As soon as hewas fit for duty, he had rejoined, and had been engaged, early andlate, in the work of drilling the recruits, and in the generalorganization of the regiment. He and Harry, however, found time totake part in any amusement that was going on. They were madewelcome in the houses of the principal merchants and otherresidents of Gottenburg, and much enjoyed their stay in the town,in spite of their longing to be back in time to take part in theearly operations of the campaign.

When they sailed into the port of Revel, they found that thecampaign had but just commenced, and they marched with all haste tojoin the force with which the king was advancing against theSaxons, who were still besieging Riga. Their army was commanded byMarshal Steinau, and was posted on the other side of the riverDwina, a broad stream. Charles the Twelfth had ridden up to ColonelJamieson's regiment upon its arrival, and expressed warmgratification at its appearance, when it was paraded for hisinspection.

"You have done well, indeed, colonel," he said. "I had hardly hopedyou could have collected so fine a body of men in so short a time."

At his request, the officers were brought up and introduced. Hespoke a few words to those he had known before, saying to Charlie:

"I am glad to see you back again, lieutenant. You have quiterecovered from that crack on your crown, I hope. But I need notask, your looks speak for themselves. You have just got back intime to pay my enemies back for it."

The prospect was not a cheerful one, when the Swedes arrived on thebanks of the Dwina. The Saxons were somewhat superior in force, andit would be a desperate enterprise to cross the river, in the teethof their cannon and musketry. Already the king had caused a numberof large flat boats to be constructed. The sides were made veryhigh, so as to completely cover the troops from musketry, and werehinged so as to let down and act as gangways, and facilitate alanding.

Charlie was standing on the bank, looking at the movements of theSaxon troops across the river, and wondering how the passage was tobe effected, when a hand was placed on his shoulder. Looking round,he saw it was the king, who, as was his custom, was moving about onfoot, unattended by any of his officers.

"Wondering how we are to get across, lieutenant?"

"That is just what I was thinking over, your majesty."

"We want another snowstorm, as we had at Narva," the king said."The wind is blowing the right way, but there is no chance of suchanother stroke of luck, at this time of year."

"No, sir; but I was thinking that one might make an artificialfog."

"How do you mean?" the king asked quickly.

"Your majesty has great stacks of straw here, collected for foragefor the cattle. No doubt a good deal of it is damp, or if not, itcould be easily wetted. If we were to build great piles of it, allalong on the banks here, and set it alight so as to burn veryslowly, but to give out a great deal of smoke, this light windwould blow it across the river into the faces of the Saxons, andcompletely cover our movements."

"You are right!" the king exclaimed. "Nothing could be better. Wewill make a smoke that will blind and half smother them;" and hehurried away.

An hour later, orders were sent out to all the regiments that, assoon as it became dusk, the men should assemble at the great foragestores for fatigue duty. As soon as they did so, they were orderedto pull

down the stacks, and to carry the straw to the bank of theriver, and there pile it in heavy masses, twenty yards apart. Thewhole was to be damped, with the exception of only a small quantityon the windward side of the heaps, which was to be used forstarting the fire.

In two hours, the work was completed. The men were then ordered toreturn to their camps, have their suppers, and lie down at once.Then they were to form up, half an hour before daybreak, inreadiness to take their places in the boats, and were then to liedown, in order, until the word was given to move forward.

This was done, and just as the daylight appeared the heaps of strawwere lighted, and dense volumes of smoke rolled across the river,entirely obscuring the opposite shore from view. The Saxons,enveloped in the smoke, were unable to understand its meaning.Those on the watch had seen no sign of troops on the bank, beforethe smoke began to roll across the water, and the general wasuncertain whether a great fire had broken out in the forage storesof the Swedes, or whether the fire had been purposely raised,either to cover the movements of the army and enable them to marchaway and cross at some undefended point, or whether to cover theirpassage.

The Swedish regiments, which were the first to cross, took theirplaces at once in the boats, the king himself accompanying them. Ina quarter of an hour the opposite bank was gained. Marshal Steinau,an able general, had called the Saxons under arms, and was marchingtowards the river, when the wind, freshening, lifted the thick veilof smoke, and he saw that the Swedes had already gained the bank ofthe river, and at once hurled his cavalry against them.

The Swedish formation was not complete and, for a moment, they weredriven back in disorder, and forced into the river. The water wasshallow, and the king, going about among them, quickly restoredorder and discipline, and, charging in solid formation, they drovethe cavalry back and advanced across the plain. Steinau recalledhis troops and posted them in a strong position, one flank beingcovered by a marsh and the other by a wood. He had time to effecthis arrangements, as Charles was compelled to wait until the wholeof his troops were across. As soon as they were so, he led themagainst the enemy.

The battle was a severe one, for the Swedes were unprovided withartillery, and the Saxons, with the advantages of position and apowerful artillery, fought steadily. Three times Marshal Steinauled his cavalry in desperate charges, and each time almostpenetrated to the point where Charles was directing the movementsof his troops; but, at last, he was struck from his horse by a blowfrom the butt end of a musket; and his cuirassiers, withdifficulty, carried him from the field. As soon as his fall becameknown, disorder spread among the ranks of the Saxons. Someregiments gave way, and, the Swedes rushing forward with loudshouts, the whole army was speedily in full flight.

This victory laid the whole of Courland at the mercy of the Swedes,all the towns opening their gates at their approach.

They were now on the confines of Poland, and the king, brave torashness as he was, hesitated to attack a nation so powerful.Poland, at that time, was a country a little larger than France,though with a somewhat smaller population, but in this respectexceeding Sweden. With the Poles themselves he had no quarrel, forthey had taken no part in the struggle, which had been carried onsolely by their king, with his Saxon troops.

The authority of the kings of Poland was much smaller than that ofother European monarchs. The office was not a hereditary one; theking being elected at a diet, composed of the whole of the noblesof the country, the nobility embracing practically every free man;and, as it was necessary, according to the constitution of thecountry, that the vote should be unanimous, the difficulties in theway of election were very great, and civil wars of constantoccurrence.

Charles was determined that he would drive Augustus, who was theauthor of the league against him, from the throne; but he desiredto do this by means of the Poles themselves, rather than to unitethe whole nation against him by invading the country. Poland wasdivided into two parts, the larger of which was Poland proper,which could at once place thirty thousand men in the field. Theother was Lithuania, with an army of twelve thousand. These forceswere entirely independent of each other. The troops were for themost part cavalry, and the small force, permanently kept up, wascomposed almost entirely of horsemen. They rarely drew pay, andsubsisted entirely on plunder, being as formidable to their ownpeople as to an enemy.

Lithuania, on whose borders the king had taken post with his army,was, as usual, harassed by two factions, that of the Prince Sapiehaand the Prince of Oginski, between whom a civil war was going on.

The King of Sweden took the part of the former, and, furnishing himwith assistance, speedily enabled him to overcome the Oginskiparty, who received but slight aid from the Saxons. Oginski'sforces were speedily dispersed, and roamed about the country inscattered parties, subsisting on pillage, thereby exciting amongthe people a lively feeling of hatred against the King of Poland,who was regarded as the author of the misfortunes that had befallenthe country.

From the day when Charlie's suggestion, of burning damp straw toconceal the passage of the river, had been attended with suchsuccess, the king had held him in high favour. There was but a fewyears' difference between their ages, and the suggestion, sopromptly made, seemed to show the king that the young Englishmanwas a kindred spirit, and he frequently requested him to accompanyhim in his rides, and chatted familiarly with him.

"I hate this inactive life," he said one day, "and would, athousand times, rather be fighting the Russians than setting thePoles by the ears; but I dare not move against them, for, wereAugustus of Saxony left alone, he would ere long set all Polandagainst me. At present, the Poles refuse to allow him to bring inreinforcements from his own country; but if he cannot get men hecan get gold, and with gold he can buy over his chief opponents,and regain his power. If it costs me a year's delay, I must waituntil he is forced to fly the kingdom, and I can place on thethrone someone who will owe his election entirely to me, and inwhose good faith I can be secure.

"That done, I can turn my attention to Russia, which, by allaccounts, daily becomes more formidable. Narva is besieged by them,and will ere long fall; but I can retake Narva when once I candepend upon the neutrality of the Poles. Would I were king ofPoland as well as of Sweden. With eighty thousand Polish horse, andmy own Swedish infantry, I could conquer Europe if I wished to doso.

"I know that you are as fond of adventure as I am, and I amthinking of sending you with an envoy I am despatching to Warsaw.

"You know that the Poles are adverse to business of all kinds. Thepoorest noble, who can scarcely pay for the cloak he wears, and whois ready enough to sell his vote and his sword to the highestbidder, will turn up his nose at honest trade; and the consequenceis, as there is no class between the noble and the peasant, thetrade of the country is wholly in the hands of Jews and foreigners,among the latter being, I hear, many Scotchmen, who, while theymake excellent soldiers, are also keen traders. This class musthave considerable power, in fact, although it be exercised quietly.The Jews are, of course, money lenders as well as traders. Largenumbers of these petty nobles must be in their debt, either formoney lent or goods supplied.

"My agent goes specially charged to deal with the archbishop, whois quite open to sell his services to me, although he poses as oneof the strongest adherents of the Saxons. With him, it is not aquestion so much of money, as of power. Being a wise man, he seesthat Augustus can never retain his position, in the face of theenmity of the great body of the Poles, and of my hostility. But,while my agent deals with him and such nobles as he indicates asbeing likely to take my part against Augustus, you could ascertainthe feeling of the trading class, and endeavour to induce them, notonly to favour me, but to exert all the influence they possess onmy behalf. As there are many Scotch merchants in the city, youcould begin by making yourself known to them, taking with youletters of introduction from your colonel, and any other Scotchgentleman whom you may find to have acquaintanceship, if not withthe men themselves, with their families in Scotland. I do not, ofcourse, say

that the mission will be without danger, but that will,I know, be an advantage in your eyes. What do you think of theproposal?"

"I do not know, sire," Charlie said doubtfully. "I have noexperience whatever in matters of that kind."

"This will be a good opportunity for you to serve anapprenticeship," the king said decidedly. "There is no chance ofanything being done here, for months, and as you will have noopportunity of using your sword, you cannot be better employed thanin polishing up your wits. I will speak to Colonel Jamieson aboutit this evening. Count Piper will give you full instructions, andwill obtain for you, from some of our friends, lists of the namesof the men who would be likely to be most useful to us. You willplease to remember that the brain does a great deal more than thesword, in enabling a man to rise above his fellows. You are a braveyoung officer, but I have many a score of brave young officers, andit was your quick wit, in suggesting the strategy by which wecrossed the Dwina without loss, that has marked you out from amongothers, and made me see that you are fit for something better thangetting your throat cut."

The king then changed the subject with his usual abruptness, anddismissed Charlie, at the end of his ride, without any furtherallusion to the subject. The young fellow, however, knew enough ofthe king's headstrong disposition to be aware that the matter wassettled, and that he could not, without incurring the king'sserious displeasure, decline to accept the commission. He walkedback, with a serious face, to the hut that the officers of thecompany occupied, and asked Harry Jervoise to come out to him.

"What is it, Charlie?" his friend said. "Has his gracious majestybeen blowing you up, or has your horse broken its knees?"

"A much worse thing than either, Harry. The king appears to havetaken into his head that I am cut out for a diplomatist;" and hethen repeated to his friend the conversation the king had had withhim.

Harry burst into a shout of laughter.

"Don't be angry, Charlie, but I cannot help it. The idea of yourgoing, in disguise, I suppose, and trying to talk over the Jewishclothiers and cannie Scotch traders, is one of the funniest thingsI ever heard. And do you think the king was really in earnest?"

"The king is always in earnest," Charlie said in a vexed tone;"and, when he once takes a thing into his head, there is nogainsaying him."

"That is true enough, Charlie," Harry said, becoming serious."Well, I have no doubt you will do it just as well as another, andafter all, there will be some fun in it, and you will be in a bigcity, and likely to have a deal more excitement than will fall toour lot here."

"I don't think it will be at all the sort of excitement I shouldcare for, Harry. However, my hope is, that the colonel will be ableto dissuade him from the idea."

"Well, I don't know that I should wish that if I were in yourplace, Charlie. Undoubtedly, it is an honour being chosen for sucha mission, and it is possible you may get a great deal of creditfor it, as the king is always ready to push forward those who dogood service. Look how much he thinks of you, because you made thatsuggestion about getting up a smoke to cover our passage."

"I wish I had never made it," Charlie said heartily.

"Well, in that case, Charlie, it is likely enough we should not betalking together here, for our loss in crossing the river underfire would have been terrible."

"Well, perhaps it is as well as it is," Charlie agreed. "But I didnot want to attract his attention. I was very happy as I was, withyou all. As for my suggestion about the straw, anyone might havethought of it. I should never have given the matter anothermoment's consideration, and I should be much better pleased if theking had not done so, either, instead of telling the colonel aboutit, and the colonel speaking to the officers, and such a ridiculousfuss being made about nothing."

"My dear Charlie," Harry said seriously, "you seem to be forgettingthat we all came out here, together, to make our fortune, or at anyrate to do as well as we could till the Stuarts come to the throneagain, and our fathers regain their estates, a matter concerningwhich, let me tell you, I do not feel by any means so certain as Idid in the old days. Then, you know, all our friends were of ourway of thinking, and the faith that the Stuarts would return waslike a matter of religion, which it was heresy to doubt for aninstant. Well, you see, in the year that we have been out hereone's eyes have got opened a bit, and I don't feel by any meanssanguine that the Stuarts will ever come to the throne of Englandagain, or that our fathers will recover their estates.

"You have seen here what good soldiers can do, and how powerlessmen possessing but little discipline, though perhaps as brave asthemselves, are against them. William of Orange has got goodsoldiers. His Dutch troops are probably quite as good as our bestSwedish regiments. They have had plenty of fighting in Ireland andelsewhere, and I doubt whether the Jacobite gentlemen, howevernumerous, but without training or discipline, could any more makehead against them than the masses of Muscovites could against theSwedish battalions at Narva. All this means that it is necessarythat we should, if possible, carve out a fortune here. So far, Icertainly have no reason to grumble. On the contrary, I have hadgreat luck. I am a lieutenant at seventeen, and, if I am not shotor carried off by fever, I may, suppose the war goes on and thearmy is not reduced, be a colonel at the age of forty.

"Now you, on the other hand, have, by that happy suggestion ofyours, attracted the notice of the king, and he is pleased tonominate you to a mission in which there is a chance of yourdistinguishing yourself in another way, and of being employed inother and more important business. All this will place you muchfarther on the road towards making a fortune, than marching andfighting with your company would be likely to do in the course oftwenty years, and I think it would be foolish in the extreme foryou to exhibit any disinclination to undertake the duty."

"I suppose you are right, Harry, and I am much obliged to you foryour advice, which certainly puts the matter in a light in which Ihad not before seen it. If I thought that I could do it well, Ishould not so much mind, for, as you say, there will be some fun tobe got out of it, and some excitement, and there seems littlechance of doing anything here for a long time. But what am I to sayto the fellows? How can I argue with them? Besides, I don't talkPolish."

"I don't suppose there are ten men in the army who do so, probablynot five. As to what to say, Count Piper will no doubt give youfull instructions as to the line you are to take, the arguments youare to use, and the inducements you are to hold out. That is sureto be all right."

"Well, do not say anything about it, Harry, when you get back. Istill hope the colonel will dissuade the king."

"Then you are singularly hopeful, Charlie, that is all I can say.You might persuade a brick wall to move out of your way, as easilyas induce the King of Sweden to give up a plan he has once formed.However, I will say nothing about it."

At nine o'clock, an orderly came to the hut with a message that thecolonel wished to speak to Lieutenant Carstairs. Harry gave hisfriend a comical look, as the latter rose and buckled on his sword.

"What is the joke, Harry?" his father asked, when Charlie had left."Do you know what the colonel can want him for, at this time of theevening? It is not his turn for duty."

"I know, father; but I must not say."

"The lad has not been getting into a scrape, I hope?"

"Nothing serious, I can assure you; but really, I must not sayanything until he comes back."

Harry's positive assurance, as to the impossibility of changing theking's decision, had pretty well dispelled any hopes Charlie mightbefore have entertained, and he entered the colonel's room with agrave face.

"You know why I have sent for you, Carstairs?"

"Yes, sir; I am afraid that I do."

"Afraid? That is to say, you don't like it."

"Yes, sir; I own that I don't like it."

"Nor do I, lad, and I told his majesty so. I said you were tooyoung for so risky a business. The king scoffed at the idea. Hesaid, 'He is not much more than two years younger than I am, and ifI am old enough to command an army,

he is old enough to carry outthis mission. We know that he is courageous. He is cool, sharp, andintelligent. Why do I choose him? Has he not saved me from the lossof about four or five thousand men, and probably a total defeat? Ayoung fellow who can do that, ought to be able to cope with Jewishtraders, and to throw dust in the eyes of the Poles.

"I have chosen him for this service for two reasons. In the firstplace, because I know he will do it well, and even those whoconsider that I am rash and headstrong, admit that I have the knackof picking out good men. In the next place, I want to reward himfor the service he has done for us. I cannot, at his age, make acolonel of him, but I can give him a chance of distinguishinghimself in a service in which age does not count for so much, andCount Piper, knowing my wishes in the matter, will push himforward. Moreover, in such a mission as this, his youth will be anadvantage, for he is very much less likely to excite suspicion thanif he were an older man.'

"The king's manner did not admit of argument, and I had only towait and ask what were his commands. These were simply that you areto call upon his minister tomorrow, and that you would then receivefull instructions.

"The king means well by you, lad, and on turning it over, I thinkbetter of the plan than I did before. I am convinced, at any rate,that you will do credit to the king's choice."

"I will do my best, sir," Charlie said. "At present, it all seemsso vague to me that I can form no idea whatever as to what it willbe like. I am sure that the king's intentions are, at any rate,kind. I am glad to hear you say that, on consideration, you thinkbetter of the plan. Then I may mention the matter to MajorJervoise?"

"Certainly, Carstairs, and to his son, but it must go no farther. Ishall put your name in orders, as relieved from duty, and shallmention that you have been despatched on service, which might meananything. Come and see me tomorrow, lad, after you have receivedCount Piper's instructions. As the king reminded me, there are manyScotchmen at Warsaw, and it is likely that some of them passedthrough Sweden on the way to establish themselves there, and I mayvery well have made their acquaintance at Gottenburg or Stockholm.

"Once established in the house of one of my countrymen, yourposition would be fairly safe and not altogether unpleasant, andyou would be certainly far better off than a Swede would be engagedon this mission. The Swedes are, of course, regarded by the Polesas enemies, but, as there is no feeling against Englishmen orScotchmen, you might pass about unnoticed as one of the family of aScottish trader there, or as his assistant."

"I don't fear its being unpleasant in the least, colonel. Nor do Ithink anything one way or the other about my safety. I only fearthat I shall not be able to carry out properly the missionintrusted to me."

"You will do your best, lad, and that is all that can be expected.You have not solicited the post, and as it is none of yourchoosing, your failure would be the fault of those who have sentyou, and not of yourself; but in a matter of this kind there is nosuch thing as complete failure. When you have to deal with one manyou may succeed or you may fail in endeavouring to induce him toact in a certain manner, but when you have to deal with aconsiderable number of men, some will be willing to accept yourproposals, some will not, and the question of success will probablydepend upon outside influences and circumstances over which youhave no control whatever. I have no fear that it will be a failure.If our party in Poland triumph, or if our army here advances, or ifAugustus, finding his position hopeless, leaves the country, thegood people of Warsaw will join their voices to those of themajority. If matters go the other way, you may be sure that theywill not risk imprisonment, confiscation, and perhaps death, bygetting up a revolt on their own account. The king will beperfectly aware of this, and will not expect impossibilities, andthere is really no occasion whatever for you to worry yourself onthat ground."

Upon calling upon Count Piper the next morning, Charlie found that,as the colonel had told him, his mission was a general one.

"It will be your duty," the minister said, "to have interviews withas many of the foreign traders and Jews in Warsaw as you can, onlygoing to those to whom you have some sort of introduction from thepersons you may first meet, or who are, as far as you can learnfrom the report of others, ill disposed towards the Saxon party.Here is a letter, stating to all whom it may concern, that you arein the confidence of the King of Sweden, and are authorized torepresent him.

"In the first place, you can point out to those you see that,should the present situation continue, it will bring grievous evilsupon Poland. Proclamations have already been spread broadcast overthe country, saying that the king has no quarrel with the people ofPoland, but, as their sovereign has, without the slightestprovocation, embarked on a war, he must fight against him and hisSaxon troops, until they are driven from the country. This you willrepeat, and will urge that it will be infinitely better that Polandherself should cast out the man who has embroiled her with Sweden,than that the country should be the scene of a long and sanguinarystruggle, in which large districts will necessarily be laid waste,all trade be arrested, and grievous suffering inflicted upon thepeople at large.

"You can say that King Charles has already received promises ofsupport from a large number of nobles, and is most desirous thatthe people of the large towns, and especially of the capital,should use their influence in his favour. That he has himself noambition, and no end to serve save to obtain peace and tranquillityfor his country, and that it will be free for the people of Polandto elect their own monarch, when once Augustus of Saxony hasdisappeared from the scene.

"In this sealed packet you will find a list of influentialcitizens. It has been furnished me by one well acquainted with theplace. The Jews are to be assured that, in case of a friendlymonarch being placed on the throne, Charles will make a treaty withhim, insuring freedom of commerce to the two countries, and willalso use his friendly endeavours to obtain, from the king and Diet,an enlargement of the privileges that the Jews enjoy. To theforeign merchants you will hold the same language, somewhataltered, to suit their condition and wants.

"You are not asking them to organize any public movement, the timehas not yet come for that; but simply to throw the weight of theirexample and influence against the party of the Saxons. Of courseour friends in Warsaw have been doing their best to bring roundpublic opinion in the capital to this direction, but the country isso torn by perpetual intrigues, that the trading classes hold aloofaltogether from quarrels in which they have no personal interest,and are slow to believe that they can be seriously affected by anychanges which will take place.

"Our envoy will start tomorrow morning. His mission is an open one.He goes to lay certain complaints, to propose an exchange ofprisoners, and to open negotiations for peace. All these are butpretences. His real object is to enter into personal communicationwith two or three powerful personages, well disposed towards us.

"Come again to me this evening, when you have thought the matterover. I shall then be glad to hear any suggestion you may like tomake."

"There is one thing, sir, that I should like to ask you. It willevidently be of great advantage to me, if I can obtain privateletters of introduction to Scotch traders in the city. This Icannot do, unless by mentioning the fact that I am bound forWarsaw. Have I your permission to do so, or is it to be kept aclose secret?"

"No. I see no objection to your naming it to anyone you canimplicitly trust, and who may, as you think, be able to give yousuch introductions, but you must impress upon them that the mattermust be kept a secret. Doubtless the Saxons have in their paypeople in our camp, just as we have in theirs, and were word ofyour going sent, you would find yourself watched, and perhapsarrested. We should, of course wish you to be zealous in yourmission, but I would say, do not be over anxious. We are not tryingto get up a revolution in Warsaw, but seeking to ensure that thefeeling in the city should be in our favour; and this, we think,may be brought about, to some extent, by such assurances as you cangive of the king's friendship, and by such expressions of a beliefin the justice of our cause, and

in the advantages there would bein getting rid of this foreign prince, as might be said openly byone trader to another, when men meet in their exchanges or upon thestreet. So that the ball is once set rolling, it may be trusted tokeep in motion, and there can be little doubt that such expressionsof feeling, among the mercantile community of the capital, willhave some effect even upon nobles who pretend to despise trade, butwho are not unfrequently in debt to traders, and who hold theirviews in a certain respect."

"Thank you, sir. At what time shall I come this evening?"

"At eight o'clock. By that time, I may have thought out fartherdetails for your guidance."

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

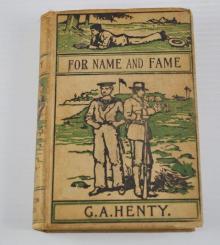

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

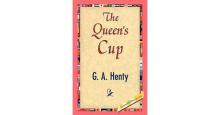

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

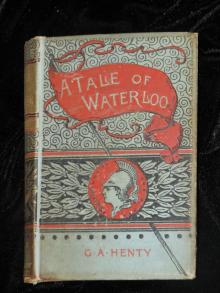

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates