- Home

- G. A. Henty

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea Page 5

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea Read online

Page 5

CHAPTER V.

A BRUSH WITH THE ENEMY

Two days later Jack obtained leave to go on shore. He hesitated for amoment whether to choose the right or left bank. The plateau ofScutari was covered with the tents of the British army, which weredaily being added to, as scarce an hour passed without a transportcoming in laden with troops. After a little hesitation, however, Jackdetermined to land at Constantinople. The camps at Scutari woulddiffer but little from those at Gallipoli, while in the Turkishcapital were innumerable wonders to be investigated. Hailing a caicquewhich was passing, he took his seat with young Coveney, who had alsogot leave ashore, and accepted with dignity the offer of a long pipe.This, however, by no means answered his expectations; the mouthpiecebeing formed of a large piece of amber of a bulbous shape, and toolarge to be put into the mouth. It was consequently necessary to suckthe smoke through the end, a practice very difficult at first to thoseaccustomed to hold a pipe between the teeth.

In ten minutes the boat landed them at Pera, close to the bridge ofboats across the Golden Horn. For a time the lads made no motion toadvance, so astonished were they at the crowd which surged across thebridge: Turkish, English, and French soldiers, Turks in turbans andfezes, Turkish women wrapped up to the eyes in white or blue clothes;hamals or porters staggered past under weights which seemed to theboys stupendous; pachas and other dignitaries riding on gayly-trappedlittle horses; carriages, with three or four veiled figures inside andblack guards standing on the steps, carried the ladies of one harem tovisit those of another. The lads observed that for the most part thesedames, instead of completely hiding their faces with thick wrappingsas did their sisters in the streets, covered them merely with a foldof thin muslin, permitting their features to be plainly seen. Theseladies evidently took a lively interest in what was going on, and inno way took it amiss when some English or French officer staredunceremoniously at their pretty faces; although their black guardsgesticulated angrily on these occasions, and were clearly far moreindignant concerning the admiration which their mistresses excitedthan were those ladies themselves.

At last the boys moved forward across the bridge, and Jack presentlyfound himself next to two young English officers proceeding in thesame direction. One of these turned sharply round as Jack addressedhis companion.

"Hallo, Jack!"

"Hallo, Harry! What! you here? I had no idea you had got yourcommission yet. How are you, old fellow, and how are they all athome?"

"Every one is all right, Jack. I thought you would have known allabout it. I was gazetted three days after you started, and was orderedto join at once. We wrote to tell you it."

"I have never had a letter since I left home," Jack said. "I supposethey are all knocking about somewhere. Every one is complaining aboutthe post. Well, this is jolly; and I see you are in the 33d too, theregiment you wanted to get into. When did you arrive?"

"We came in two days ago in the 'Himalaya.' We are encamped with therest of the light division who have come up. Sir George Brown commandsus, and will be here from Gallipoli in a day or two with the rest ofthe division."

The boys now introduced their respective friends to each other, andthe four wandered together through Constantinople, visited thebazaars, fixed upon lots of pretty things as presents to be bought andtaken home at the end of the war, and then crossed the bridge again toPera, and had dinner at Missouri's, the principal hotel there, and thegreat rendezvous of the officers of the British army and navy. Thenthey took a boat and rowed across to Scutari, where Harry did thehonors of the camp, and at sundown Jack and his messmate returned onboard the "Falcon."

The next three weeks passed pleasantly, Jack spending all his time,when he could get leave, with his brother, and the latter often comingoff for an hour or two to the "Falcon." Early in May the news arrivedthat the Russians had advanced through the Dobrudscha and hadcommenced the siege of Silistria. A few hours later the "Falcon" andseveral other ships of war were on their way up the Dardanelles,convoying numerous store-ships bound to Varna. Shortly afterwards thegenerals of the allied armies determined that Varna should be the basefor the campaign against the Russians, and accordingly towards the endof May the troops were again embarked.

Varna is a seaport, surrounded by an undulating country of park-likeappearance, and the troops were upon their arrival delighted withtheir new quarters. Here some 22,000 English and 50,000 French wereencamped, together with 8,000 or 10,000 Turks. A few days after theirarrival Jack obtained leave for a day on shore, and rowed out toAlladyn, nine miles and a half from Varna, where the light division,consisting of the 7th, 19th, 23d, 33d, 77th, and 88th regiments, wasencamped. Close by was a fresh-water lake, and the undulated groundwas finely wooded with clumps of forest timber, and covered withshort, crisp grass. No more charming site for a camp could beconceived. Game abounded, and the officers who had brought guns withthem found for a time capital sport. Everyone was in the highestspirits, and the hopes that the campaign would soon open in earnestwere general. In this, however, they were destined to be disappointed,for on the 24th of June the news came that the Turks had unaidedbeaten off the Russians with such heavy loss in their attack uponSilistria that the latter had broken up the siege, and were retreatingnorthward.

A weary delay then occurred while the English and French homeauthorities, and the English and French generals in the field weresettling the point at which the attack should be made upon Russia. Thedelay was a disastrous one, for it allowed an enemy more dangerousthan the Russians to make his insidious approaches. The heat was verygreat; water bad, indeed almost undrinkable, the climate wasnotoriously an unhealthy one, and fruit of all kinds, together withcucumbers and melons, extremely cheap, and the soldiers consequentlyconsumed very large quantities of these.

Through June and up to the middle of July, however, no very evilconsequences were apparent. On the 21st of July two divisions ofFrench troops under General Canrobert marched into the Dobrudscha, insearch of some bodies of Russians who were said to be there. On thenight of the 28th cholera broke out, and before morning, in onedivision no less than 600 men lay dead. The other divisions, althoughsituated at considerable distances, were simultaneously attacked withequal violence, and three days later the expedition returned, havinglost over 7000 men. Scarcely less sudden or less fatal was the attackamong the English lines, and for some time the English camps wereravaged by cholera.

Jack was extremely anxious about his brother, for the light divisionsuffered even more severely than did the others. But he was not ableto go himself to see as to the state of things, for the naval officerswere not allowed to go on shore more than was absolutely necessary.And as the camp of the light division had been moved some ten milesfarther away on to the slopes of the Balkans, it would have beenimpossible to go and return in one day. Such precautions as weretaken, however, were insufficient to keep the cholera from on boardship. In a short time the fleet was attacked with a severity almostequal to that on shore, and although the fleet put out to sea, theflagship in two days lost seventy men.

Fortunately the "Falcon" had left Varna before the outbreak extendedto the ships. The Crimea had now been definitely determined upon asthe point of assault. Turkish vessels with heavy siege guns were ontheir way to Varna, and the "Falcon" was ordered to cross to theCrimea and report upon the advantages of several places for thelanding of the allied army. The mission was an exciting one, as besidethe chance of a brush with shore batteries, there was the possibilitythat they might run against some of the Russian men-of-war, who stillheld that part of the Black Sea, and whose headquarters were atSebastopol, the great fortress which was the main object of theexpedition to the Crimea.

The "Falcon" started at night, and in the morning of the second daythe hills of the Crimea were visible in the distance. The fires werethen banked up and she lay-to. With nightfall she steamed on untilwithin a mile or two of the coast, and here again anchored. With theearly dawn steam was turned on, and the "Falcon" steamed along asclose to the shore as she dare go,

the lead being constantly keptgoing, as but little was known of the depth of water on these shores.Presently they came to a bay with a smooth beach. The ground rose butgradually behind, and a small village stood close to the shore.

"This looks a good place," Captain Stuart said to the firstlieutenant. "We will anchor here and lower the boats. You, Mr.Hethcote, with three boats, had better land at that village, get anyinformation that you can, and see that there are no troops about. Ifattacked by a small force, you will of course repel it; if by a strongone, fall back to your boats, and I will cover your retreat with theguns of the ship. The other two boats will be employed in sounding.Let the master have charge of these, and make out, as far as he can, aperfect chart of the bay."

In a few minutes the boats were lowered, and the men in the highestglee took their places. Jack was in the gig with the first lieutenant.The order was given, and the boats started together towards the shore.They had not gone fifty yards before there was a roar of cannon,succeeded by the whistle of shot. Two masked batteries, one upon eachside of the bay, and mounting each six guns, had opened upon them. Thecutter, commanded by the second lieutenant, was smashed by a roundshot and instantly sunk. A ball struck close to the stroke-oar of thegig, deluging its occupants with water and ricochetting over thegunwale of the boat, between the stroke-oar and Mr. Hethcote. Two shothulled the "Falcon," and others whistled through her rigging.

"Pick up the crew of the cutter, Mr. Hethcote, and return on board atonce," Captain Stuart shouted; the engines of the "Falcon" at oncebegan to move, and the captain interposed the ship between the nearestbattery and the boats, and a few seconds later her heavy guns, whichhad previously been got ready for action, opened upon the forts. Intwo minutes the boats were alongside with all hands, save one of thecutter's crew who had been cut in two by the round shot. The men,leaving the boats towing alongside, rushed to the guns, and the heavyfire of the "Falcon" speedily silenced her opponents. Then, as hisobject was to reconnoitre, not to fight, Captain Stuart steamed out tosea. He was determined, however, to obtain further informationrespecting the bay, which appeared to him one adapted for the purposeof landing.

"I will keep off till nightfall, Mr. Hethcote. We will then run in asclose as we dare, showing no lights, and I will then ask you to take aboat with muffled oars to row to the village. Make your way among thehouses as quietly as possible, and seize a couple of fishermen andbring them off with you. Our interpreter will be able to find out fromthem at any rate, general details as to the depth of water and thenature of the anchorage."

"Who shall I take with me, sir?"

"The regular gig's crew and Mr. Simmonds. He has passed, and it maygive him a chance of promotion. I think, by the way, you may as welltake the launch also; it carries a gun. Do not let the men from itland, but keep her lying a few yards off shore to cover your retreatif necessary. Mr. Pascoe will command it."

There was a deep but quiet excitement among the men when at nightfallthe vessel's head was again turned towards shore, and the crews of thegig and launch told to hold themselves in readiness. Cutlasses weresharpened and pistols cleaned. Not less was the excitement in themidshipmen's berth, where it was known that Simmonds was to go in thegig; but no one knew who was to accompany the launch. However, Jackturned out to be the lucky one, Mr. Pascoe being probably glad toplease the first lieutenant by selecting his relation, although thatofficer would not himself have shown favoritism on his behalf.

It was about eleven o'clock when the "Falcon" approached her formerposition, or rather to a point a mile seaward of it as nearly as themaster could bring her, for the night was extremely dark and the landscarcely visible. Not a light was shown, not a voice raised on board,and the only sound heard was the gentle splash of the paddles as theyrevolved at their slowest rate of speed. The falls had been greased,the rowlocks muffled, and the crew took their places in perfectsilence.

"You understand, Mr. Hethcote," were Captain Stuart's last words,"that you are not to attempt a landing if there is the slightestopposition."

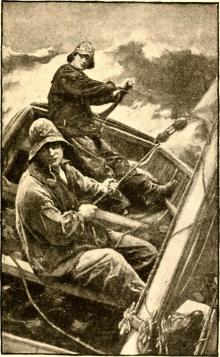

Very quietly the boats left the "Falcon's" side. They rowed abreastand close to each other, in order that the first lieutenant could giveorders to Mr. Pascoe in a low tone. The men were ordered to rowquietly, and to avoid any splashing or throwing up of water. It was alonger row than they had expected, and it was evident that the master,deceived by the uncertain light, had brought the vessel up at a pointconsiderably farther from the shore than he had intended. As they gotwell in the bay they could see no lights in the village ahead; but anoccasional gleam near the points at either side showed that the men inthe batteries were awake and active. As the boat neared the shore themen rowed, according to the first lieutenant's orders, more and moregently, and at last, when the line of beach ahead became distinctlyvisible, the order was given to lie upon their oars. All listenedintently, and then Mr. Hethcote put on his helm so that the boat whichhad still some way on it drifted even closer to the launch.

"Do you hear anything, Mr. Pascoe?"

"I don't know, sir. I don't seem to make out any distinct sound, butthere certainly appears to be some sort of murmur in the air."

"So I think, too."

Again they listened.

"I don't know, sir," Jack whispered in Mr. Pascoe's ear, "but I fancythat at times I see a faint light right along behind those trees. Itis very faint, but sometimes their outline seems clearer than atothers."

Mr. Pascoe repeated in a low voice to Mr. Hethcote what Jack hadremarked.

"I fancied so once or twice myself," he said. "There," he addedsuddenly, "that is the neigh of a horse. However, there may be horsesanywhere. Now we will paddle slowly on. Lay within a boat's length ofthe shore, Mr. Pascoe, keep the gun trained on the village, and letthe men hold their arms in readiness."

In another minute the gig's bow grated on the beach. "Quietly, lads,"the first lieutenant said. "Step into the water without splashing.Then follow me as quickly as you can."

The beach was a sandy one, and the footsteps of the sailors werealmost noiseless as they stole towards the village. The place seemedhushed in quiet, but just as they entered the little street a figurestanding in the shade of a house rather larger than the rest, steppedforward and challenged, bringing, as he did so, his musket to thepresent. An instant later he fired, just as the words, "A Russiansentry," broke from the first lieutenant's lips. Almost simultaneouslythree or four other shots were fired at points along the beach. Arocket whizzed high in the air from each side of the bay, a buglesounded the alarm, voices of command were heard, and, as if byenchantment, a chaos of sounds followed the deep silence which hadbefore reigned, and from every house armed men poured out.

"Steady, lads, steady!" Mr. Hethcote shouted. "Fall back steadily.Keep together, don't fire a shot till you get to the boat; then givethem a volley and jump on board. Now, retire at the double."

For a moment the Russians, as they poured from the houses, paused inignorance of the direction of their foes, but a shout from the sentryindicated this, and a scattering fire was opened. This, however, wasat once checked by the shout of the officer to dash forward with allspeed after the enemy. As the mass of Russians rushed from thevillage, the howitzer in the bows of the launch poured a volley ofgrape into them, and checked their advance. However, from along thebushes on either side fresh assailants poured out.

"Jump on board, lads, jump on board!" Mr. Hethcote shouted, and eachsailor, discharging his musket at the enemy, leapt into his place."Give them a volley, Mr. Pascoe. Get your head round and row. Don'tlet the men waste time in firing."

The volley from the launch again momentarily checked the enemy, andjust as she got round, another discharge from the gun further arrestedthem. The boats were not, however, thirty yards from the shore beforethis was lined with dark figures who opened a tremendous fire ofmusketry.

"Row, lads, row!" Mr. Pascoe shouted to his men. "We shall be out oftheir sight in another hundred yards."

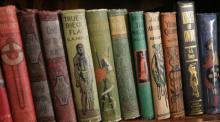

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

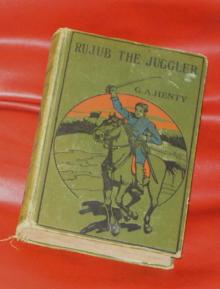

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

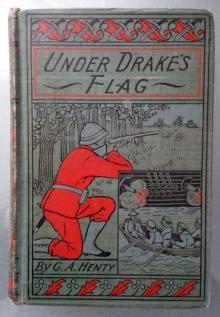

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

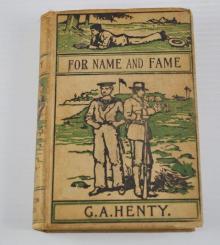

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates