- Home

- G. A. Henty

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea Page 6

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea Read online

Page 6

CHAPTER VI.

THE ALMA

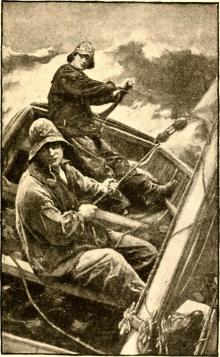

Desperately the men bent to their oars, and the heavy boat surgedthrough the water. Around them swept a storm of musket balls, andalthough the darkness and their haste rendered the fire of theRussians wild and uncertain, many of the shot took effect. With asigh, Mr. Pascoe fell against Jack, who was sitting next to him, justat the moment when Jack himself experienced a sensation as if a hotiron had passed across his arm. Several of the men dropped their oarsand fell back, but the boats still held rapidly on their way, and intwo or three minutes were safe from anything but random shot. At thismoment, however, three field pieces opened with grape, and the ironhail tore up the water near them. Fortunately they were now almost outof sight, and although the forts threw up rockets to light the bay,and joined their fire to that of the field guns, the boat escapeduntouched.

"Thank God we are out of that!" Mr. Hethcote said, as the fire ceasedand the boats headed for a light hung up to direct then.

"Have you many hurt, Mr. Pascoe?"

"I'm afraid, sir, Mr. Pascoe is either killed or badly wounded. He islying against me, and gives no answer when I speak to him."

"Any one else hurt?" Mr. Hethcote asked in a moment.

The men exchanged a few words among themselves.

"There are five down in the bottom of the boat, sir, and six or sevenof us have been hit more or less."

"It's a bad business," Mr. Hethcote said. "I have two killed and threewounded here. Are you hit yourself, Mr. Archer?"

"I've got a queer sensation in my arm, sir, and don't seem able to useit, so I suppose I am, but I don't think it's much."

"Pull away, lads," Mr. Hethcote said shortly. "Show a light there inthe bow to the steamer."

The light was answered by a sharp whistle, and they heard the beat ofthe paddles of the "Falcon" as she came down towards them, and fiveminutes later the boats were hoisted to the davits. "No casualties, Ihope, Mr. Hethcote?" Captain Stuart said, as the first lieutenantstepped on board. "You seem to have got into a nest of hornets."

"Yes, indeed, sir. There was a strong garrison in the village, and wehave suffered, I fear heavily. Some eight or ten killed and as manywounded."

"Dear me, dear me!" Captain Stuart said. "This is an unfortunatecircumstance, indeed. Mr. Manders, do you get the wounded on board andcarried below. Will you step into my cabin, Mr. Hethcote, and give mefull details of this unfortunate affair?"

Upon mustering the men, it was found that the total casualties in thetwo boats of the "Falcon" amounted to, Lieutenant Pascoe killed,Midshipman Archer wounded; ten seamen killed, and nine wounded. Jack'swound was more severe than he had at first thought. The ball had gonethrough the upper part of the arm, and had grazed and badly bruisedthe bone in its passage. The doctor said he would probably be someweeks before he would have his arm out of a sling. The "Falcon" spentanother week in examining the Crimean coast, and then ran across againto Varna. Here everything was being pushed forward for the start. Oversix hundred vessels were assembled, with a tonnage vastly exceedingthat of any fleet that had ever sailed the seas. Twenty-seven thousandEnglish and twenty-three thousand French were to be carried in thishuge flotilla; for although the French army was considerably largerthan the English, the means of sea-transport of the latter werevastly superior, and they were able to take across the whole of theirarmy in a single trip; whereas, the French could convey but halfof their force. Unfortunately, between Lord Raglan, the EnglishCommander-in-Chief, and Marshal Saint Arnaud, the French commander,there was little concert or agreement. The French, whose arrangementswere far better, and whose movements were prompter than our own, werealways complaining of British procrastination; while the EnglishGeneral went quietly on his own way, and certainly tried sorely thepatience of our allies. Even when the whole of the allied armies wereembarked, nothing had been settled beyond the fact that they weregoing to invade the Crimea, and the enormous fleet of men-of-war andtransports, steamers with sailing vessels in tow, extending in linesfarther than the eye could reach, and covering many square miles ofthe sea, sailed eastward without any fixed destination. Theconsequence was, as might be expected, a lamentable waste of time.Halts were called, councils were held, reconnaissances sent forward,and the vast fleet steamed aimlessly north, south, east, and west,until, when at last a landing-place was fixed upon, near Eupatoria,and the disembarkation was effected, fourteen precious days had beenwasted over a journey which is generally performed in twenty-fourhours, and which even the slowly moving transports might have easilyaccomplished in three days.

The consequence was the Russians had time to march round large bodiesof troops from the other side, and the object of the expedition--thecapture of Sebastopol by a _coup de main_--was altogether thwarted. Nomore imposing sight was ever seen than that witnessed by the bands ofCossacks on the low shores of the Crimea, when the allied fleetsanchored a few miles south of Eupatoria. The front extended nine milesin length, and behind this came line after line of transports untilthe very topmasts of those in the rear scarce appeared above thehorizon. The place selected for the landing-place was known as the OldFort, a low strip of bush and shingle forming a causeway between thesea and a stagnant fresh-water lake, known as Lake Saki.

At eight o'clock in the morning of the 14th of September, the Frenchadmiral fired a gun, and in a little more than an hour six thousand oftheir troops were ashore, while the landing of the English did notcommence till an hour after. The boats of the men-of-war andtransports had already been told off for the ships carrying the lightdivision, which was to be the first to land, and in a wonderfullyshort time the sea between the first line of ships and the shore wascovered with a multitude of boats crowded with soldiers. The boats ofthe "Falcon" were employed with the rest, and as three weeks hadelapsed since Jack had received his wound, he was able to take hisshare of duty, although his arm was still in a sling. The ship towhich the "Falcon's" boats were told off lay next to that which hadcarried the 33d, and as he rowed past, he exchanged a shout and a waveof the hand with Harry, who was standing at the top of thecompanion-ladder, seeing the men of his company take their seats inthe boats. It was a day of tremendous work. Each man and officercarried three days' provisions, and no tents or other unnecessarystores were to be landed. The artillery, however, had to be gotashore, and the work of landing the guns on the shingly beach was alaborious one indeed. The horses in vain tugged and strained, and thesailors leaped over into the water and worked breast high at thewheels, and so succeeded in getting them ashore. Jack had askedpermission from Captain Stuart to spend the night on shore with hisbrother, and just as he was going off from the ship for the last time.Simmonds, who had obtained his acting commission in place of Mr.Pascoe, said, "Archer, I should advise you to take a tarpaulin and acouple of bottles of rum. They will be useful before morning, I cantell you, for we are going to have a nasty night."

Indeed the rain was already coming down steadily, and the wind wasrising. Few of those who took part in it will ever forget their firstnight in the Crimea. The wind blew pitilessly, the rain poured down intorrents, and twenty-seven thousand Englishmen lay without shelter inthe muddy fields, drenched to the skin. Jack had no trouble in findinghis brother's regiment, which was in the advance, some two or threemiles from the landing-place. Harry was delighted to see him, and thesight of the tarpaulin and bottles did not decrease the warmth of hiswelcome. Jack was already acquainted with most of the officers of the33d.

"Hallo, Archer," a young ensign said, "if I had been in your place, Ishould have remained snugly on board ship. A nice night we are infor!"

So long as the daylight lasted, the officers stood in groups andchatted of the prospects of the campaign. There was nothing to do--nopossibility of seeing to the comforts of their men. The place wherethe regiment was encamped was absolutely bare, and there were no meansof procuring any shelter whatever.

"How big is that tarpaulin, Jack?"

"About twelve feet square," Jack said, "and pretty heavy I fou

nd it, Ican tell you."

"What had we better do with it?" asked Harry. "I can't lie down underthat, you know, with the colonel sitting out exposed to this rain."

"The best thing," Jack said after a minute's consideration, "would beto make a sort of tent of it. If we could put it up at a slant, somesix feet high in front with its back to the wind, it would shelter alot of fellows. We might hang some of the blankets at the sides."

The captain and lieutenant of Harry's company were taken intoconsultation, and with the aid of half a dozen soldiers, some musketsbound together and some ramrods, a penthouse shelter was made. Somesods were laid on the lower edge to keep it down. Each side was closedwith two blankets. Some cords from one of the baggage carts were usedas guy ropes to the corners, and a very snug shelter was constructed.This Harry invited the colonel and officers to use, and although thespace was limited, the greater portion of them managed to sit down init, those who could not find room taking up their places in front,where the tent afforded a considerable shelter from the wind and rain.No one thought of sleeping. Pipes were lighted, and Jack's two bottlesof rum afforded a tot to each. The night could scarcely be called acomfortable one, even with these aids; but it was luxurious, indeed,in comparison with that passed by those exposed to the full force ofthe wind.

The next morning Jack said good-bye to his brother and the officers ofthe regiment, to whom he presented the tarpaulin for future use, andthis was folded up and smuggled into an ammunition cart. It was not,of course, Jack's to give, being government property, but he would beable to pay the regulation price for it on his return. Half an hourlater, Jack was on the beach, where a high surf was beating. All daythe work of landing cavalry and artillery went on under the greatestdifficulties. Many of the boats were staved and rendered useless, andseveral chargers drowned. It was evident that the weather was breakingup, and the ten days of lovely weather which had been wasted at seawere more bitterly regretted than ever. No tents were landed, and thetroops remained wet to the skin, with the additional mortification ofseeing their French allies snugly housed under canvas, while even the4000 Turks had managed to bring their tents with them. The naturalresult was that sickness again attacked the troops, and hundreds wereprostrated before, three days later, they met the enemy on the Alma.The French were ready to march on the 17th, but it was not until twodays later, that the British were ready; then at nine o'clock in themorning the army advanced. The following is the list of the Britishforce. The light division under Sir George Brown--2d Battalion RifleBrigade, 7th Fusiliers, 19th Regiment, 23d Fusiliers, under BrigadierMajor-General Codrington; 33d Regiment, 77th Regiment, 88th Regiment,under Brigadier-General Butler. First division, under the Duke ofCambridge--The Grenadier, Coldstream and Scots Fusilier Guards, underMajor-General Bentinck; the 42d, 79th and 93d Highlanders, underBrigadier-General Sir C. Campbell. The second division, under Sir DeLacy Evans--The 30th, 55th, and 95th, under Brigadier-GeneralPennefather; the 41st, 47th and 49th, under Brigadier-General Adams.The third division under Sir R. England--The 1st, 28th and 38th underBrigadier-General Sir John Campbell; the 44th, 50th, and 68thRegiments under Brigadier-General Eyre. Six companies of the fourthwere also attached to this division. The fourth division under SirGeorge Cathcart consisted of the 20th, 21st, 2d Battalion RifleBrigade, 63d, 46th and 57th, the last two regiments, however, had notarrived. The cavalry division under Lord Lucan consisted of the LightCavalry Brigade under Lord Cardigan, composed of the 4th LightDragoons, the 8th Hussars, 11th Hussars, 13th Dragoons and 17thLancers; and the Heavy Cavalry Brigade under Brigadier-GeneralScarlett, consisting of the Scots Greys, 4th Dragoon Guards, 5thDragoon Guards, and 6th Dragoons. Of these the Scots Greys had not yetarrived.

It was a splendid sight, as the allied army got in motion. On theextreme right, and in advance next the sea, was the first division ofthe French army. Behind them, also by the sea, was the second divisionunder General Canrobert, on the left of which marched the thirddivision under Prince Napoleon. The fourth division and the Turksformed the rearguard. Next to the third French division was the secondBritish, with the third in its rear in support. Next to the seconddivision was the light division, with the Duke of Cambridge's divisionin the rear in support. The Light Cavalry Brigade covered the advanceand left flank, while along the coast, parallel with the march of thetroops, steamed the allied fleet, prepared, if necessary, to assistthe army with their guns. All were in high spirits that the months ofweary delay were at last over, and that they were about to meet theenemy. The troops saluted the hares which leaped out at their feet atevery footstep as the broad array swept along, with shouts of laughterand yells, and during the halts numbers of the frightened creatureswere knocked over and slung behind the knapsacks to furnish a meal atthe night's bivouac. The smoke of burning villages and farmhousesahead announced that the enemy were aware of our progress.

Presently, on an eminence across a wide plain, masses of the enemy'scavalry were visible. Five hundred of the Light Cavalry pushed on infront, and an equal number of Cossacks advanced to meet them. LordCardigan was about to give the order to charge when masses of heavycavalry made their appearance. Suddenly one of these extended and abattery of Russian artillery opened fire upon the cavalry. Ourartillery came to the front, and after a quarter of an hour's duel theRussians fell back; and soon after the army halted for the night, at astream called the Boulyanak, six miles from the Alma, where theRussians, as was now known, were prepared to give battle. The weatherhad now cleared again, and all ranks were in high spirits as they satround the bivouac fires.

"How savage they will be on board ship," Harry Archer said to CaptainLancaster, "to see us fighting a big battle without their having ahand in it. I almost wonder that they have not landed a body ofmarines and blue-jackets. The fleets could spare 4000 or 5000 men, andtheir help might be useful. Do you think the Russians will fight?"

"All soldiers will fight," Captain Lancaster said, "when they've got astrong position. It needs a very different sort of courage to lie downon the crest of a hill and fire at an enemy struggling up it in fullview, to that which is necessary to make the assault. They have tooall the advantage of knowing the ground, while we know absolutelynothing about it. I don't believe that the generals have any more ideathan we have. It seems a happy-go-lucky way of fighting altogether.However, I have no doubt that we shall lick them somehow. It seems,though, a pity to take troops direct at a position which the enemyhave chosen and fortified, when by a flank march, which in anundulating country like this could be performed without the slightestdifficulty, we could turn the position and force them to retreat,without losing a man."

Such was the opinion of many other officers at the time. Such has beenthe opinion of every military critic since. Had the army made a flankmarch, the enemy must either have retired at once, or have been liableto an attack upon their right flank, when, if beaten, they would havebeen driven down to the sea-shore under the guns of the ships, andkilled or captured, to a man. Unfortunately, however, owing to thejealousies between the two generals, the illness of Marshal Arnaud,and the incapacity of Lord Raglan, there was neither plan nor concert.The armies simply fought as they marched, each general of divisiondoing his best and leading his men at that portion of the enemy'sposition which happened to be opposite to him. The sole understandingarrived at was that the armies were to march at six in the morning;that General Bosquet's division, which was next to the sea, was,covered by guns of the ships, to first carry the enemy's positionthere; and that when he had obtained a footing upon the plateau, ageneral attack was to be made. Even this plan, simple as it was, wasnot fully carried out, as Lord Raglan did not move his troops tillnine in the morning. Three precious hours were therefore wasted, and apursuit after the battle which would have turned the defeat into arout was therefore prevented, and Sebastopol saved, to cost tens ofthousands of lives before it fell. The Russian position on the Almawas along a crest of hills. On their left by the sea these roseprecipitously, offering great difficulties for an assault. Furth

erinland, however, the slope became easy, and towards the right centreand right against which the English attack was directed, the hill wassimply a slope broken into natural terraces, on which were many wallsand vineyards. Near the sea the river ran between low banks, butinland the bank was much steeper, the south side rising some thirty orforty feet, and enabling its defenders to sweep the ground acrosswhich the assailants must advance. While on their left the Russianforces were not advanced in front of the hill which formed theirposition, on the lower ground they occupied the vineyards andinclosures down to the river, and their guns were placed in batterieson the steps of the slope, enabling them to search with their fire thewhole hill-side as well as the flat ground beyond the river.

The attack, as intended, was begun by General Bosquet. Bonat's brigadecrossed the river by a bar of sand across the mouth where the waterwas only waist-deep, while D'Autemarre's brigade crossed by a bridge,and both brigades swarmed up the precipitous cliffs which offeredgreat difficulties, even to infantry. They achieved their object,without encountering any resistance whatever, the guns of the fleethaving driven back the Russian regiment appointed to defend this post.The enemy brought up three batteries of artillery to regain the crest,but the French with tremendous exertions succeeded in getting up abattery of guns, and with their aid maintained the position they hadgained.

When the sound of Bosquet's guns showed that his part of the programmewas carried into effect, the second and third divisions of the Frencharmy crossed the Alma, and were soon fiercely engaged with the enemy.Canrobert's division for a time made little way, as the river was toodeep for the passage of the guns, and these were forced to make adetour. Around a white stone tower some 800 yards on their left, densemasses of Russian infantry were drawn up, and these opened sotremendous a fire upon the French that for a time their advance waschecked. One of the brigades from the fourth division, which was inreserve, advanced to their support, and joining with some of theregiments of Canrobert's division, and aided by troops whom GeneralBosquet had sent to their aid, a great rush was made upon the densebody of Russians, who, swept by the grape of the French artillery,were unable to stand the impetuous attack, and were forced to retirein confusion. The French pressed forward and at this point also of thefield, the day was won.

In the mean time the British army had been also engaged. Long beforethey came in sight of the point which they were to attack they heardthe roar of cannon on their right, and knew that Bosquet's divisionwere engaged. As the troops marched over the crest of the roundedslopes they caught glimpses of the distant fight. They could seemasses of Russian infantry threatening the French, gathered on theheight, watch the puffs of smoke as the guns on either side sent theirmessengers of death, and the white smoke which hung over the fleet asthe vessels of war threw their shells far over the heads of the Frenchinto the Russian masses. Soon they heard the louder roar whichproclaimed that the main body of the French army were in action, andburning with impatience to begin, the men strode along to take theirshare in the fight. Until within a few hundred yards of the river thetroops could see nothing of it, nor the village on its banks, for theground dipped sharply. Before they reached the brow twelve Russianguns, placed on rising ground some 300 yards beyond the river, openedupon them.

"People may say what they like," Harry Archer said to his captain,"but a cannon-ball makes a horribly unpleasant row. It wouldn't behalf as bad if they would but come silently."

As he spoke a round shot struck down two men a few files to his right.They were the first who fell in the 33d.

"Steady, lads, steady," shouted the officers, and as regularly as ifon field-day, the English troops advanced. The Rifles, under MajorNorthcote, were ahead, and, dashing through the vineyards under a rainof fire, crossed the river, scaled the bank, and pushed forward to thetop of the next slope. It was on the plateau beyond that the Russianmain body were posted, and for a time the Rifles had hard work tomaintain themselves. In the meantime, the Light Division wereadvancing in open order, sometimes lying down, sometimes advancing,until they gained the vineyards. Here the regular order which they hadso far maintained was lost, as the ground was broken up by hedges,stone walls, vines and trees. The 19th, 7th, 23d and 33d were thenled, at a run, right to the river by General Codrington, their coursebeing marked by killed and wounded, and crossing they shelteredthemselves under the high bank. Such was the state of confusion inwhich they arrived there that a momentary pause was necessary toenable the men of the various regiments to gather together, and theenemy, taking advantage of this, brought down three battalions ofinfantry, who advanced close to the bank, and, as the four regimentsdashed up it, met them with a tremendous fire. As hotly it wasanswered, and the Russians retired while their batteries again openedfire.

There was but little order in the British ranks as they struggledforward up the hill. Even under this tremendous fire the men paused topick grapes, and all the exertions of their officers could notmaintain the regular line of advance. From a rising ground a Russianregiment kept up a destructive fire upon them, and the guns in thebatteries on their flank fired incessantly. The slaughter wastremendous, but the regiments held on their way unflinchingly. In afew minutes the 7th had lost a third of their men, and half the 23dwere down. Not less was the storm of fire around the 33d. Confused,bewildered and stunned by the dreadful din, Harry Archer struggled onwith his company. His voice was hoarse with shouting, though hehimself could scarce hear the words he uttered. His lips were parchedwith excitement and the acrid smell of gunpowder. Man after man hadfallen beside him, but he was yet untouched. There was no thought offear or danger now. His whole soul seemed absorbed in the one thoughtof getting into the battery. Small as were the numbers who stillstruggled on, their determined advance began to disquiet the Russians.For the first time a doubt as to victory entered their minds. When theday began they felt assured of it. Their generals had told them thatthey would annihilate their foes, their priests had blessed them, andassured them of the protection and succor of the saints. But theBritish were still coming on, and would not be denied. The infantrybehind the battery began to retire. The artillery, left unprotected,limbered up in haste, and although three times as numerous as the menof the Light Division, the Russians, still firing heavily, retired upthe hill, while, with a shout of triumph the broken groups of the 23d,the 19th, and 33d burst into the battery, capturing a gun which theRussians had been unable to withdraw.

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire

With Clive in India; Or, The Beginnings of an Empire The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars

The Cornet of Horse: A Tale of Marlborough's Wars Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War

Friends, though divided: A Tale of the Civil War The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred

The Dragon and the Raven; Or, The Days of King Alfred The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal

The Young Carthaginian: A Story of The Times of Hannibal With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War

With Lee in Virginia: A Story of the American Civil War A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes

A Knight of the White Cross: A Tale of the Siege of Rhodes With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent

With Wolfe in Canada: The Winning of a Continent A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection

A March on London: Being a Story of Wat Tyler's Insurrection Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest

Wulf the Saxon: A Story of the Norman Conquest For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem

For the Temple: A Tale of the Fall of Jerusalem The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars

The Young Colonists: A Story of the Zulu and Boer Wars By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico

By Right of Conquest; Or, With Cortez in Mexico A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti

A Roving Commission; Or, Through the Black Insurrection at Hayti The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru

The Treasure of the Incas: A Story of Adventure in Peru At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War

At the Point of the Bayonet: A Tale of the Mahratta War St. George for England

St. George for England A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories

A Soldier's Daughter, and Other Stories Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril

Among Malay Pirates : a Tale of Adventure and Peril In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence

In Greek Waters: A Story of the Grecian War of Independence The Second G.A. Henty

The Second G.A. Henty In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain

In the Irish Brigade: A Tale of War in Flanders and Spain With Moore at Corunna

With Moore at Corunna Tales of Daring and Danger

Tales of Daring and Danger By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson

By Conduct and Courage: A Story of the Days of Nelson With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations

With the Allies to Pekin: A Tale of the Relief of the Legations Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War

Under Wellington's Command: A Tale of the Peninsular War In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado

In the Heart of the Rockies: A Story of Adventure in Colorado Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy

Out with Garibaldi: A story of the liberation of Italy Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains

Redskin and Cow-Boy: A Tale of the Western Plains The Lost Heir

The Lost Heir In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy

In the Reign of Terror: The Adventures of a Westminster Boy With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War

With Frederick the Great: A Story of the Seven Years' War A Girl of the Commune

A Girl of the Commune In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers

In the Hands of the Cave-Dwellers At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt

At Aboukir and Acre: A Story of Napoleon's Invasion of Egypt Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow

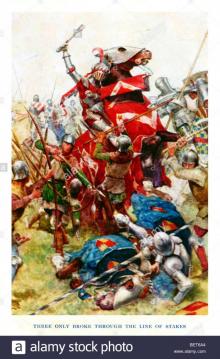

Through Russian Snows: A Story of Napoleon's Retreat from Moscow At Agincourt

At Agincourt Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines

Facing Death; Or, The Hero of the Vaughan Pit: A Tale of the Coal Mines With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan: A Story of Atbara and Omdurman Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War

Maori and Settler: A Story of The New Zealand War Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea

Jack Archer: A Tale of the Crimea On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War

On the Irrawaddy: A Story of the First Burmese War Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California

Captain Bayley's Heir: A Tale of the Gold Fields of California By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic

By Pike and Dyke: a Tale of the Rise of the Dutch Republic_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 1 (of 3) True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence

True to the Old Flag: A Tale of the American War of Independence When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire

When London Burned : a Story of Restoration Times and the Great Fire The Golden Canyon

The Golden Canyon By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War

By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War In Times of Peril: A Tale of India

In Times of Peril: A Tale of India St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers

St. George for England: A Tale of Cressy and Poitiers The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain

The Bravest of the Brave — or, with Peterborough in Spain Rujub, the Juggler

Rujub, the Juggler Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main

Under Drake's Flag: A Tale of the Spanish Main A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 2 For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes

For Name and Fame; Or, Through Afghan Passes The Queen's Cup

The Queen's Cup One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo

One of the 28th: A Tale of Waterloo Colonel Thorndyke's Secret

Colonel Thorndyke's Secret A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 3 The Young Buglers

The Young Buglers_preview.jpg) By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604)

By England's Aid; or, the Freeing of the Netherlands (1585-1604) A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1

A Search For A Secret: A Novel. Vol. 1 In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce

In Freedom's Cause : A Story of Wallace and Bruce On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers

On the Pampas; Or, The Young Settlers Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti

Through Three Campaigns: A Story of Chitral, Tirah and Ashanti Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way

Sturdy and Strong; Or, How George Andrews Made His Way_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 3 (of 3)_preview.jpg) Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3)

Dorothy's Double. Volume 2 (of 3) No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee

No Surrender! A Tale of the Rising in La Vendee The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt

The Cat of Bubastes: A Tale of Ancient Egypt A Jacobite Exile

A Jacobite Exile Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion

Beric the Briton : a Story of the Roman Invasion By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604

By England's Aid; Or, the Freeing of the Netherlands, 1585-1604 With Clive in India

With Clive in India Bountiful Lady

Bountiful Lady The G.A. Henty

The G.A. Henty Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower

Both Sides the Border: A Tale of Hotspur and Glendower Bonnie Prince Charlie

Bonnie Prince Charlie A Knight of the White Cross

A Knight of the White Cross In The Reign Of Terror

In The Reign Of Terror Bravest Of The Brave

Bravest Of The Brave Beric the Briton

Beric the Briton With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman

With Kitchener in the Soudan : a story of Atbara and Omdurman The Young Carthaginian

The Young Carthaginian Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots

Through The Fray: A Tale Of The Luddite Riots Among Malay Pirates

Among Malay Pirates